Chapter 30: Largest

David M. Williams

R&D Department

St. Joseph Health System

Orange, CA 92868

April 21, 2001

The largest living insect species, by virtue of having the greatest visible body mass and probably weight, are the giant scarabs, Goliathus goliatus, Goliathus regius, Megasoma elephas, Megasoma actaeon, and the immense cerambycid, Titanus giganteus. No clear winner can be declared on the basis of objective data, the candidates being nearly equal in this regard, but a visual comparison of all of them, side by side and scaled to maximum known size, may convince one otherwise. The heaviest weight reliably reported for any insect is 71 grams for the protected giant weta, Deinacrida heteracantha, of New Zealand.

For the purposes of this chapter, "largest insect" shall mean the species whose largest representatives have the greatest body mass. Weight data could more clearly define the winners, were it available with adequate documentation, and if taken in conjunction with corresponding body measurements. Such is not the case, however, and length-to-width-to-thickness measurements, taking into account the density of the exoskeleton and visible body volume are the criterion used to separate these five beetles from amongst other competitive candidates.

Methods

Discussions with collectors and professionals, first-hand measurements of very large specimens, searches of primary and secondary literature and website articles - none have provided comparative evidence favoring one insect over all of the others. Several sources do offer reliable maximum body lengths. First-hand dry weight and linear measurements of six to ten large specimens of each of the five giant beetle species were collected. Subsequent comparison of this variety of measurements was helpful to ascertain whether the proportions of giant specimens might change somewhat as the upper limits of size were reached. Except for slight incremental horn development of the scarabs, this was generally not the case. From the recorded data, graphic images were scaled to simulate the maximum size for each chosen beetle species so they could at least be compared visually.

Dry weight data was considered only as evidence for the peripheral discussion on the relevance of weight in comparing potential winners.

Results

Until further relevant data is available, five beetle species are likely co-title holders for Largest Insect. Beetles were selected due to their obvious density and greater measurable bulk. Though a gravid specimen of the cricket-like giant weta, Deinacrida heteracantha, of New Zealand had a reported weight of 71 grams (Moffett 1991), weight data is lacking for nearly all of the beetles and extreme measurements of Deinacrida indicate it is smaller in bulk. Obviously, a maximum Titanus is compelling in comparison of top views, but there is yet no evidence that one of 16.7cm has a measurably greater volume than the giant scarabs.

Discussion

Perhaps few other popular subjects discussed among entomologists, amateur and professional alike, have engendered such interest and generated such a plethora of opinions, all claiming at least some supporting data, as that of the "largest/heaviest/bulkiest" insect. Gilbert J. Arrow (1951), in his analysis of the form and function of horn development of giant beetles, unequivocally states that the elephant beetles (Megasoma actaeon and Megasoma elephas) are the largest and bulkiest of all insects. H.E. Jacques (1951), author of How to Know the Beetles, concurs that "Megasoma actaeon Linne from South America, is likely the largest and heaviest beetle known." Ross H. Arnett (1968) states in a footnote to the Scarabaeidae chapter of his The Beetles of the United States, "This family [Scarabaeidae] includes the Goliath beetle, G. goliathus L. from Africa, probably the largest insect known." and "The tribe Goliathini, which contains the largest of all insects, Goliathus goliathus Drury 1770, from West Africa..." Patrick Bleuzen (1994), who personally captured the largest known specimen of Titanus giganteus in French Guiana, writes of Titanus, "it is certainly the most bulky of all insects."

Unfortunately, maximum sizes are universally expressed as a maximum total body length or, much less frequently, as an isolated weight. Single linear measurements are given in Endrötti’s (1985) The Dynastinae of the World, Lachaume’s (1983) The Beetles of the World, Vol. 3, Goliathini 1, and Bleuzen’s (1994) The Beetles of the World, Vol. 21, Prioninae. Bleuzen even comments about the unfortunate stretching of specimens to attain unrealistic sizes (further emphasizing the deficiencies of dependence on a maximum body measurement).

Other close contenders, such as Megasoma mars, a glossy black giant from equatorial Brazil, and the beautiful East African Goliathus orientalis, which may reach a body length of over 10.5cm, were excluded because neither has ever been claimed by specialists to be a contender for largest insect and, more importantly, no specimens of competitive size could be documented. If weight alone were the only consideration here and none of the beetles exceeded their projected maximum live weights, the all-time, conditional winner of "heaviest insect" would have to be bestowed on a lone gravid giant weta specimen from New Zealand.

Finally, to avoid the unintentional errors of many popular writers, every attempt has been made to exclude hearsay data from this discussion. Several exceptional linear measurements were reported in the course of this research which, were they credible, could have tilted the decision in favor of nearly any one of the top five beetle species. Needless to say, documentation of still larger specimens than those quoted herein is expected and welcomed. After all, many of the linear maxes accepted for this comparison are beyond the limits published in sources quoted above.

Acknowledgements

Thanks for technical services from Bob Grosso, Orange County Division of Weights and Measures, Anaheim, CA, and Jerri Larrson, BioQuip Products, Inc., Gardena, CA.

Thanks to the following private collectors, museum workers and professionals for their assistance in examining specimens and for their valued comments for inclusion in the text: Peter Brink, private collector; Cameron Campbell, natural historian; Rosser Garrison, Economic Entomologist, Los Angeles County, CA; Brian Harris, Curatorial Assistant, Entomology Department, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History; David Hawks, Staff Research Associate, Entomology Museum, University of California, Riverside; Frank Hovore, tropical biologist/New World Cerambycidae taxonomist; Phil Mays, private collector/exhibitor; Dr. Mary McIntyre, School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand; L. Milani, Professor of Medicine, private collector; Dana Onishi, correspondent/private collector; Brett Ratcliffe, Curator and Professor, Systematics Research Collections, University of Nebraska; Bill Reid, correspondent/private collector; Scott Smith, correspondent/private collector; and Jay Timberlake, correspondent/private collector.

Special thanks to Eleanor Brewer, M.B.A., M.Ed., Vice President, R&D Dept, SJHS, for text criticism, to Doug Yanega, Sr. Museum Scientist, Entomology Research Museum, University of California, Riverside, for facilitating email contacts and for reviewing the manuscript, and to Thomas J. Walker, Editor, UF Book of Insect Records, for critiquing the text.

All photographs and graphic imagery, except where credited, were prepared by the author.

References Cited

- Arnett, Ross H. 1968. The Beetles of the United States. Am. Entomol. Inst., Ann Arbor, MI. pp. 395, 427.

- Arrow, Gilbert J. 1951. Horned Beetles. W. Junk, The Hague. pp. 21, 22.

- Beebe, William. 1944. The function of secondary sexual characters in two species of Dynastinae (Coleoptera). Zoologica (New York) 29: 56.

- Bleuzen, Patrick. 1994. The Beetles of the World, Vol. 21, Macrodontini & Prionini 1.

- Endrötti, Sebo. 1985. The Dynastinae of the World, Vol 28. W. Junk, The Hague.

- Hardy, Alan R. 1972. A brief revision of the North and Central American species of Megasoma. Canadian Entomologist 104: 767-777.

- Jaques, H.E. 1951. How to Know the Beetles. Wm Brown Company, Dubuque, IA. pp. 169, 233.

- Lachaume, Gilbert. 1983. The Beetles of the World, Vol. 5, Dynastini. Science Nat, Compiegne [France].

- Lachaume, Gilbert. 1983. The Beetles of the World, Vol. 3, Goliathini 1. Science Nat, Compiegne [France].

- MacQuitty, M., & L. Mound. 1994. Megabugs: the Natural History Museum Book of Insects. Barnes & Noble, London.

- Moffett, Mark W. 1991. Wetas - New Zealand’s insect giants. National Geographic 180(5): 100-105.

- Sakai, Kaoru and Shinji, Sagai. 1998. The Cetoniine Beetles of the World. Shizuma Printing Company. p. 203.

- Sharell, Richard. 1971. New Zealand Insects and Their Story. Collins, Auckland. pp. 136-139, 176.

- Tillyard, R.J. 1926. The Insects of Australia and New Zealand. Angus & Robertson, Sydney. Plate 8.

- Wood, Gerald L. 1982. The Guinness Book of Animal Facts & Feats. Guinness Superlatives, Enfield, Middlesex. pp. 170-171

- Wood, Rev. J.G. 1874. Insects Abroad. Longman & Company, pp. 136,137, 231.

- Zahl, Paul. 1959. Giant insects of the Amazon. National Geographic 115(5): 662.

Notes

Weight Problems

Weight is sometimes offered as a criterion for largest, and the "heaviest insect" has been cautiously identified by several popular authors, notably Wood (1982) in The Guinness Book of Animal Facts & Feats, and McQuitty and Mound (1994) in Megabugs. Figures such as 100 grams for Goliathus (species not specified) versus a mere 35 grams for Megasoma elephas (McQuitty & Mound) are interesting of themselves, but have no comparative value whatever. Was the decimal misplaced, 35 grams to 3.5 ounces? Or, more probably, was 35 grams misquoted as 3.5 ounces and the unknown Goliathus, in fact, weighed 35 grams? Neither length nor width, let alone feeding condition, was given for the above-quoted Megasoma weight. An average-sized living specimen of M. actaeon measuring 10.3cm was reported to weigh 36 grams (Beebe 1944). By a straight math comparison, that equals about 47 grams for a maximum M. actaeon. A large living Goliathus goliatus of approximately 10cm total length was recently reported to weigh 42 grams (C. Campbell, personal communication). The same extrapolation of data applied to actaeon would produce a figure of about 45 grams for a living 11cm Goliathus.

Considering the voracious feeding habits of Megasoma (Hovore, personal communication), giant specimens may vary widely in live weight within the same species and same length. Both Megasoma and the longer-horned Dynastes hercules have been observed in captivity to consume nearly an entire avocado in one day, ingesting both pulp and juice. Goliathus, a fruit and sap feeder, may consume comparable quantities of food, while Titanus, on the other hand, is not known to feed as an adult and, therefore, may never bulk up as the scarabs can.* A fair comparison, if it were possible to perform at all, might be to record live weight, under controlled conditions, of a series of starved specimens of all three genera. Linear measurements representing several widths plus the thickness, in addition to the total length of each test specimen, must accompany any relevant weight data.

But Goliathus is heavier, isn’t it? Given that dry weights of Goliathus are not greater than Titanus or Megasoma, and given that Goliathus is not visibly greater in bulk, there is yet no reason to believe that Goliathus is the heaviest insect or that it would necessarily outweigh a giant Megasoma, certainly not three times over. The lack of relevant comparative data has spawned some academic speculation among collectors, the argument being when comparing Goliathus vs. Megasoma, that Goliathus should be heavier by virtue of its thicker exoskeleton and legs, coupled with less air space underneath the elytra. But if this is true, then dry weight comparisons should support this contention. As yet they do not.

Of the data collected for this study and mathematically incremented up to the maximum size for dry-weight comparison, Megasoma was often the heavier beetle by a few grams.** Of course, this point is by no means conclusive, given the range of data surveyed and the unknown factors bearing on total weight of living and preserved individuals of both genera, but it does nevertheless point to the need for better data collection on which to base a conclusion. Weight data has been and may remain inconclusive to decide a winner among earth’s largest living insects.

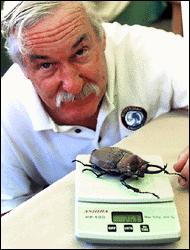

Popular West Coast exhibitor Phil Mays weighs in with two of his heavy-weights, two of the heaviest insects weighed dry for this comparison. Such comparisons provide peripheral evidence indicating the relative bulk and density of giant insect exoskeletons. |

|

* This remains to be seen, as one of the heaviest dry specimens measured for this writing was a 15.5cm Titanus. The one exception among Goliathus was the weight of a relatively fresh 10.5+ specimen of G. goliatus, which probably was not dried out yet. All other specimens examined had been preserved for many years.

** In fact, the heaviest dry weight recorded by this author was for a 12cm M. actaeon at 27.6 grams.

Maximum Lengths

Maximum body lengths of the giant weta and male specimens of the world’s bulkiest beetles, including horns and mandibles, accepted from reliable sources are:

- Deinacrida heteracantha: the cricket-like giant weta of Little Barrier Island, New Zealand – 8.5cm (11cm including ovipositor. Legspan: over 7 inches)

- Titanus giganteus: Equatorial Brazil, French Guiana – 16.7cm

- Megasoma elephas elephas: the elephant beetle, from southern Mexico to South America – 13.7cm

- Megasoma actaeon: Northern and Equatorial South America (two ssp: actaeon and janus) – 13.5cm

- Goliathus goliatus: the goliath beetle (from Central and West-Central Africa), and the less common Goliathus regius (the royal goliath beetle, Ivory Coast, Nigeria) – 11cm***

*** An inquiry to one of the authors of The Cetoniine Beetles of the World (Sakai & Sagai 1998) regarding their published record of 11.5cm for G. regius remains unanswered. That figure is herein taken as a typo.

Length Problems

A Length is a Length – Not

Differences in preparing specimens for study - not maintaining the body/head/horn alignment with the central axis of the body, raising or lowering of the head/horn, stretching the thorax or head forward beyond its natural position and unnaturally bending body segments out of position - any of these and, especially, combinations of these methods can greatly affect the total length of a specimen, making a relevant comparison of two specimens of the same species which are the same measured length, impossible. Visit any insect exhibition and you may see Titanus which have gained a "neck" by pulling the head forward out of the thorax. Therefore, a select variety of measurements was taken for all specimens examined by the author.

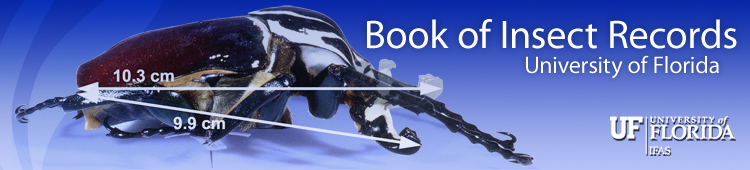

Goliathus goliatus male, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Measuring Beetles 101

Angling of the head and/or thorax, especially vertically, can significantly alter linear measurement, creating an unrealistic size estimate. Width measurements of the humeral region and pronotum should always be taken into consideration, since they will not change (unless the specimen has been crushed).

The Titanus at right is from the Rosser Garrison collection.

Open Wide

The tips of the mandibles are broken off in many Titanus specimens and the mandibles set at varying angles, making linear measurements of total body length inaccurate for precise comparison of specimens. Should the giant of them all, at 16.7cm, have incomplete mandibles, its total length may actually be closer to 17cm.

Extra Millimeters

The posterior abdominal segments of several species of large female Prioninae are sometimes distended apically to aid oviposition. That Titanus females could reach a length of 17+ or even 22+cm in this condition has been contended as an explanation for its more outlandish size estimates. Photographic evidence (which cannot be reproduced here) indicates extension of the abdomen of Titanus females of 0 to 12%. The largest known female Titanus measures 15cm to the tip of the elytra, so 12% extension would theoretically increase that length to 16.8cm.

Horns

Bigger Beetles = Bigger Horns

Gilbert J. Arrow (1951) discusses the existence and utility for the incremental development of horns on the thorax and heads of the males of certain large scarab beetles, mostly of the subfamily Dynastinae, and the similar development of giant mandibles for large stag and long-horn beetles. The common theme is that horn development is greater for larger specimens, sometimes attaining grotesque proportions in giants.

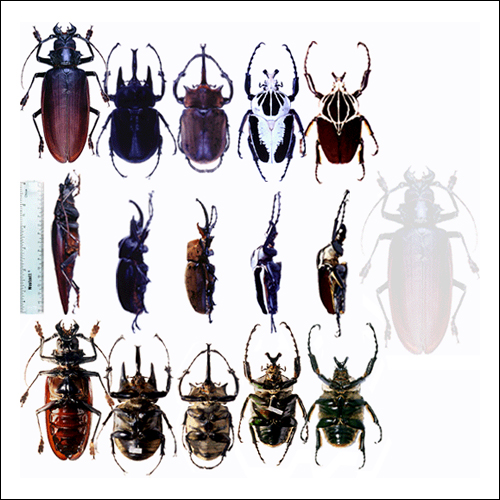

Photo Gallery

Top, side, and bottom views of the five bulkiest insects in the World, compared to a 15-cm (6-inch) scale at left. Images are graphically-sized representations of the five species at their maximum known sizes. Scale was achieved by comparing widths first, then body length.

From left to right the species are:

- Titanus giganteus: French Guiana, Brazil – 16.7cm

- Megasoma actaeon: Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil – 13.5cm

- Megasoma elephas: Mexico through Venezuela – 13.7cm

- Goliathus regius: Ghana, Ivory Coast – 11cm

- Goliathus goliatus: Equatorial Africa, central and east – 11cm

Ghosted to the right of the documented sizes, also to scale, is the mythical "9-inch Titanus" of popular lore.

Titanus Sizes

The Rev. J.G. Wood wrote in his book, Insects Abroad (1874), of a nine-inch Titanus which he had before him on his desk as he wrote his chapter on the Prioninae. No doubt, this single reference is the historical basis for much, if not all, of the speculation about the size of this huge insect. Obviously, if Wood’s comment referred to the body length of Titanus, and the existence of such monsters could be proven, we would have an extremely short discussion about the "world’s largest insect."

Rev. Wood goes on to comment conservatively about other measurements of large insects. For him, Goliathus tops out at "four inches and a quarter and its breadth exactly 2 inches" (<10.8 × 5.2cm), easily within the accepted limit. Megasoma is reported as reaching five inches long and a width of two inches. Of Titanus he writes, "being the largest insect in existence, measuring nine inches in length, and being very wide and thick of body... I should very much like to have it engraved, but it is so large that no space would be found for it even if a whole page were given up to it." (The print format of the book is 4" × 6".)

Perhaps the most logical conclusion is that he referred to the total length, including outstretched antenna (interesting in itself, as the antenna of Titanus, having a very rigid pedicel, does not easily bend forward); or that the figure is merely a typo and he meant to write "six" rather than "nine" inches.

Tropical biologist Frank Hovore has stated that the average size of Titanus is about 13.5cm and specimens exceeding 15cm are considered rare where it is most commonly collected in the steamy rainforests of French Guiana and Brazil. Runts of 9-10cm are known, giving Titanus an impressive size range, characteristic of many giant beetle species. Adults live for about three to four weeks and are not known to feed. Capable and willing to snap a standard lead pencil or ballpoint pen in two with a single bite or to shatter a plastic ruler carelessly held too close for a field measurement, Titanus is feisty quarry for the lucky collector. When pursued too closely, specimens have been known to turn and approach a collector, antenna waving and jaws snapping ominously. Females are smaller than males and seldom collected, as they are not attracted to the elaborate 2000 watt light traps used to entice the males. Little is known of the life history of Titanus and what natural enemies it may have in nature.

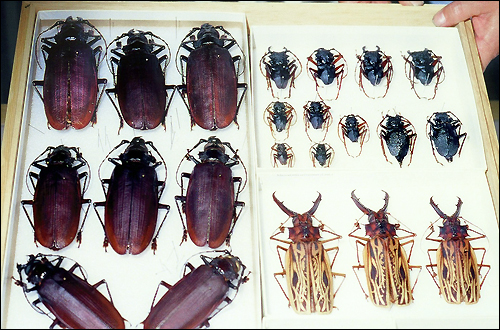

Titanus on Display

The average museum drawer for insects will hold anywhere from dozens to hundreds of specimens, but not if it's filled with Titanus and company. Macrodontia cervicornis males, which sometimes measure over 16cm, are in the bottom right corner.

This fine series was collected by permit along the Route de Belizon, French Guiana, by Mr. Frank Hovore, who has studied living specimens of several of the giants mentioned in this article.

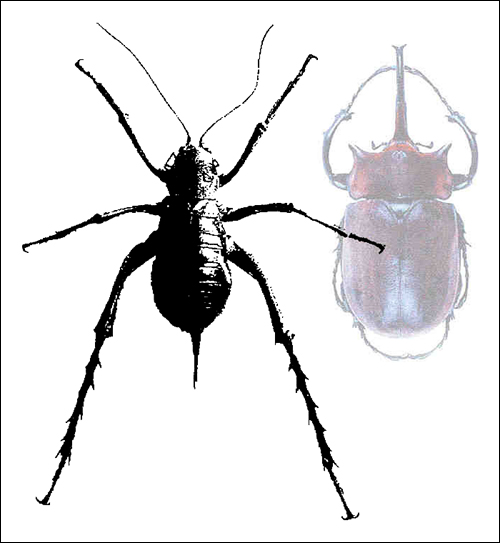

Giant Weta

Deinacrida heteracantha. The endangered giant weta of Little Barrier Island, New Zealand, is reliably credited with a maximum weight of 71 grams. The image at far left was "fattened" to simulate a gravid female with a body over 8.5cm long, excluding ovipositor. To its right is what may be the smallest of the five "largest" insects included in this discussion (Megasoma e. elephas, illustrated to scale at a total length of 13.7cm).

Weta composite based on a b&w plate in The Insects of Australia and New Zealand, by R.J. Tillyard (1926).

According to Dr. Mary IcIntyre, weights up to 43 grams are reached and maintained by adult female wetas after weeks of accumulating eggs following their final molt. When eggs are not released through normal oviposition, such as the case of captive specimens like the 71 gram example, egg accumulation continues and can result in weights far in excess of 43 grams. Without eggs, an average adult D. heteracantha would weigh about 19 grams.

Bite Marks

|

Bite marks found on the elytra of some specimens could possibly have been made by large bats during the beetle’s nocturnal flights. Elytron of Titanus giganteus from the Frank Hovore collection. |

© Copyright 2001 David M. Williams. This chapter may be freely reproduced and distributed for noncommercial purposes. For more information on copyright, see Copyright & Permitted Uses.