- Most wasps are least active at night, when in the nest. Locate the nest during daylight, then treat it after dark by directing the insecticide into the nest opening.

- Use a red-lens flashlight during the treatment to minimize wasp awareness.

- Dusts are easy to apply to some hornet and yellowjacket nests whether above or below the ground. However, it may be preferable in some circumstances to use a formulation that tends to "freeze" the insects on contact.

- There may be more than one entrance to underground nests.

- If the ground is relatively smooth and soft around the entrances, placing a metal or hard plastic container upside down over the entrance holes after treating will help ensure control. Place weights on the containers to hold them snugly against the ground.

- The extension tube on a hand duster can be inserted into the nest opening. Two or three strong puffs of dust filter through the nest and usually kill the colony within 24 hours.

- Solutions and emulsions should be sprayed into and onto the nests. The more nearly saturated the nest, the quicker the kill.

- Wear a protective bee suit when attempting to control yellowjackets.

- Some people have tried to remove a hornet nest by suddenly covering it with a plastic trash bag, tying the bag tightly to the branch, and then sawing the branch off. Don't do it. Bald faced hornets can escape from trash bags with ease.

II. SPIDERS

Brown recluse spider. The brown recluse spider, Loxosceles

reclusa, is a dusky tan or brown spider with the widest range of any recluse

spider in the U.S. — from central Texas north to Oklahoma, Kansas and Iowa, and

south through Illinois, North and South Carolina, northwestern Georgia and

Alabama, with a few sightings in adjacent states and where they have been

transported in luggage and household furnishings. Other species of recluse

spiders live in the Southwest, particularly in desert areas. This spider lives

outdoors in the southern part of its range and primarily indoors throughout the

rest of its distribution. It is commonly found in older homes in the Midwest.

The brown recluse is smaller than the black widow. It has an oval abdomen rather

than a round one. The abdomen is uniformly tan to brown without marking. A dark,

fiddle-shaped mark is obvious on the cephalothorax: The broad base of the fiddle

begins at the eyes and the narrow fiddle neck ends just above the attachment of

the abdomen. Legs are long, with the second pair longer than the first. The

brown recluse makes a fine, irregular web. It commonly wanders in the evening in

indoor infestations. Another medically important spider, the hobo spider, is

restricted to the Northwest.

Brown recluse spider. The brown recluse spider, Loxosceles

reclusa, is a dusky tan or brown spider with the widest range of any recluse

spider in the U.S. — from central Texas north to Oklahoma, Kansas and Iowa, and

south through Illinois, North and South Carolina, northwestern Georgia and

Alabama, with a few sightings in adjacent states and where they have been

transported in luggage and household furnishings. Other species of recluse

spiders live in the Southwest, particularly in desert areas. This spider lives

outdoors in the southern part of its range and primarily indoors throughout the

rest of its distribution. It is commonly found in older homes in the Midwest.

The brown recluse is smaller than the black widow. It has an oval abdomen rather

than a round one. The abdomen is uniformly tan to brown without marking. A dark,

fiddle-shaped mark is obvious on the cephalothorax: The broad base of the fiddle

begins at the eyes and the narrow fiddle neck ends just above the attachment of

the abdomen. Legs are long, with the second pair longer than the first. The

brown recluse makes a fine, irregular web. It commonly wanders in the evening in

indoor infestations. Another medically important spider, the hobo spider, is

restricted to the Northwest.

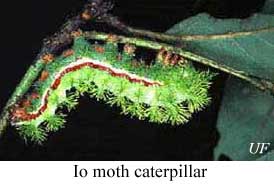

IV. URTICATING CATERPILLARS

|

|

|

V. THE MEDICAL ASPECT OF STINGS

- Remove the sting with a sideways scraping movement of a fingernail, credit card or dull knife to prevent more venom from being pumped in by the venom sac.

- Apply a paste of baking soda and cold cream or of wet salt within five minutes of sting, when possible, and apply an ice pack to relieve pain and calamine lotion to relieve itching.

- Watch for any unusual reaction, such as the appearance of red blotches anywhere on the body within two to 20 minutes, or breathing difficulties. Breathing difficulty indicates a serious response, requiring medical attention within 15 to 20 minutes.

- Seek medical attention immediately if a person with health problems is stung by an insect.

- Stay with the victim until medical care is obtained.

University of Florida and the American Mosquito Control Association

Public Health Pest Control WWW site at http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/fasulo/vector/

Additional Resources:

- Arachnology Home Page

- FDACS-DPI - Venomous Spiders in Florida - widow and recluse species

- Nova - Tales From the Hive

- UF/IFAS - bumble bees

- UF/IFAS - brown recluse spider

- UF/IFAS - European fire ant

- UF/IFAS - fire ant presentation

- UF/IFAS - hornets and yellowjackets

- UF/IFAS - IPM for ants in schools

- UF/IFAS - IPM for hornets and yellowjackets in schools

- UF/IFAS - IPM for spiders in schools

- UF/IFAS - io moth

- UF/IFAS - little fire ant

- UF/IFAS - red imported fire ant

- UF/IFAS - saddleback caterpillar

- UF/IFAS - southern house spider

- UF/IFAS - velvet ants (wasps)

- USDA - Areawide Suppression of Fire Ants

Return to Public Health Pest Control Menu

http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/fasulo/vector/