common name: brown-banded cockroach

scientific name: Supella longipalpa (Fabricius) (Insecta: Blattodea: Ectobiidae, formerly Blattellidae)

Introduction - Synonymy - Distribution - Description - Life Cycle - Medical Importance - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

The brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa (Fabricius), is a small domestic (cockroaches that live their entire life indoors) cockroach species. This species derives its name from two prominent bands present on nymphs and adults. The brown-banded cockroach resembles the German cockroach (Blattella germanica) with its small size and body shape, but it can be distinguished by the absence of two dark pronotal stripes.

Figure 1. Dorsal view of a male brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa Fabricius. Photograph by James L. Castner, University of Florida.

Figure 2. Dorsal view of a female brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa Fabricius. Photograph by James L. Castner, University of Florida.

Synonymy (Back to Top)

Supella longipalpa (Fabricius, 1798)

Blatta longipalpa Fabricius, 1798

Blatta supellectilium Serville, 1838

Blatta cubensis Saussure, 1862

Blatta phalerata Saussure, 1863

Blatta incisa Walker, F., 1868

Blatta extenuata Walker, F., 1868

Ischnoptera quadriplaga Walker, F., 1868

Ischnoptera vacillans Walker, F., 1868

Blatta transversalis Walker, F., 1871

Blatta subfasciata Walker, F., 1871

Obtained from: http://eol.org/pages/613531/names/synonyms

Distribution (Back to Top)

Rehn (1945) suggested the origin of the brown-banded cockroach is Africa. Additionally this species is thought to have been transported from Cuba to the United States, where it was collected in 1903 in Miami (Rehn 1945). Several records in Europe suggested the brown-banded cockroach was introduced by U.S. troops during World War II, across the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean in the late 1940s or early 1950s (Schal 2011). In North America, the brown-banded cockroach is thought to be present in most states (probably not in Alaska), in buildings maintained at relatively high temperature (Ebeling 1978).

The brown-banded cockroach is sometimes referred as the “furniture cockroach” because it tends to distribute throughout residences, including non-food-containing environments such as the bedroom, under tables, and behind pictures on the walls (Schal 2011). This species favors higher resting locations with 92.5% of all oothecae (egg cases) deposited on the upper third of walls (Benson and Huber, 1988). However, several surveys show the distribution range and abundance of this species are declining. Kinfu and Erko (2008) conducted a survey in central Ethiopia, which is thought to be the area of origin of the brown-banded cockroach, but did not recover any specimens of this species among 2,240 cockroaches collected in Addis Ababa. Additionally, only 10% of the 4,240 cockroaches collected in Ziway were the brown-banded cockroach. The brown-banded cockroach was the major household pest in Hawaii in a 1948 survey (Zimmerman 1948), but it was about 23-fold less abundant than the German cockroach 37 years later (Toyama et al. 1986). This decline is thought to be caused by the increasing use of air-conditioners, eliminating the ideal temperature and humidity for this species to thrive indoors (Schal 2011).

Description (Back to Top)

Eggs: The ootheca (egg case) (Figure 3) of this species is relatively small (5 mm), with a yellowish or reddish-brown color (Schal 2011). The females normally carry the fully developed ootheca at the tip of their abdomen for 24 to 36 hours and attach it to coarse surfaces such as cardboard or sand after the ootheca is hardened (Benson and Huber, 1988). Oothecae are commonly found in clusters when population density is high (Schal 2011).

Figure 3. A fully developed and detached ootheca of the brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa Fabricius. Photograph by Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida.

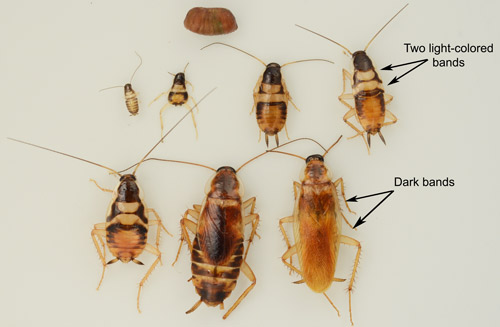

Nymphs: Two light colored bands are present behind the posterior margin of the mesonotum (the second segment of the thorax) and dorsal side of the first several segments of abdomen (Figure 4), distinguishing them from nymphs of other cockroach species.

Adults: The adult males (13-14.5 mm) are longer than the adult females (10-12 mm), but females are more robust (Cornwell 1968). Two dark bands consisting of horizontal stripes can be found on the closed wings (Figure 4). The males fly when disturbed and the females cannot fly (Ebeling 1978). Males have wings covering the full length of the abdomen, however the wings of females are shorter than the abdomen. Additionally, the female brown-banded cockroach has a distinctly larger abdomen than the male.

Figure 4. The life stages of the brown-banded cockroach, Supella longipalpa Fabricius, showing an ootheca (first row), five instars of nymphs (second row and first individual in third row) and both sexes of adults (third row). Photograph by Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida.

Life Cycle (Back to Top)

The life cycle of the brown-banded cockroach consists of the eggs (enclosed in an ootheca), 6-8 nymphal instars and the adults (Cornwell 1968). Each ootheca usually contains 18 eggs, with an average hatch rate of 13.2% (Ebeling 1978). According to Tsai and Chi (2007), the life history of this species varies significantly with temperature. At the highest temperature (33°C) tested, preadult development (including eggs and nymph stage) took about 80 days, with both sexes of adults living for about 80 days. However, preadult development took 124 days, with both sexes of adults living for about 60 days at 25°C. Each adult female was shown to produce about 13 oothecae in her lifetime at 33°C. Tsai and Chi (2007) concluded that the brown-banded cockroach was expected to establish and thrive in environments with temperatures ranging from 25°C to 33°C.

Medical Importance (Back to Top)

Domestic cockroaches such as the German cockroach and brown-banded cockroach are closely associated with humans and have the potential to adversely affect human health. According to Kramer and Brenner (2009), cockroaches are recognized as one of the most important sources of allergens, with about half of asthmatics allergic to cockroaches. Allergens from cockroaches include cast skins and excrement. Some symptoms of cockroach-induced allergies include sneezing, skin reactions, and eye irritation (Wirtz 1980).

Management (Back to Top)

The first step to control brown-banded cockroach is to correctly identify this species. Because this species is exclusively domestic, an integrated pest management (IPM) approach for indoor cockroaches could be used. Like German cockroaches, brown-banded cockroaches are most difficult to control in multi-family structures (e.g., apartments, condominiums, dormitories). Because the brown-banded cockroach prefers warm environments, places such as small crevices, electronic equipment, and storage cabinets should be carefully inspected. Baited traps (e.g. gel and station type) can be used to control cockroach populations. It is necessary to check baits monthly until the population decreases and refill empty traps with fresh bait. Additionally, structure modifications such as caulking cracks and crevices may help reduce populations of brown-banded cockroaches. The use of pesticides may be necessary when infestation is heavy, in which case a combination of a liquid insecticide and an insect growth regulator (e.g., hydroprene or pyriproxyfen) can be placed in cracks and crevices. It is important to strictly following label instructions when insecticides are used. Additionally, a parasitic wasp, Comperia merceti (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae), was shown to parasitize oothecae of the brown-banded cockroach and cause the collapse of the cockroach population (Coler et al. 1984).

Detailed information about effective control of cockroaches can be found at: Cockroaches and Their Management

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Benson EP, Huber I. 1988. Oviposition behavior and site preference of the brownbanded cockroach, Supella longipalpa (F.) (Dictyoptera: Blattellidae). Journal of Entomological Science 24: 84-91.

- Cornwell PB. 1968. The cockroach. Vol. I: A Laboratory Insect and an Industrial Pest. Hutchinson & Co. Ltd, London. 391 pp.

- Coler RR, Vandriesche RG, Elkinton JS. 1984. Effect of an oothecal parasitoid, Comperia merceti (Compere) (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae), on a population of the brownbanded cockroach (Orthoptera: Blattellidae). Environmental Entomology 13: 603-606.

- Ebeling W. 1978. Urban Entomology. The Regents of the University of California, Sacramento, CA. 695 pp.

- Kinfu A, Erko B. 2008. Cockroaches as carriers of human intestinal parasites in two localities in Ethiopia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 102: 1143-1147.

- Kramer RD, Brenner RJ. 2009. Cockroaches (Blattaria). In Mullen GR, Durden LA (Eds.), Medical and Veterinary Entomology, 2nd edition. Elsevier, Burlington, MA. 637 pp.

- Rehn JAG. 1945. Man’s uninvited fellow traveller - the cockroach. Science Monthly 61: 265-270.

- Schal C. 2011. Cockroaches. In Mallis A (Eds.), Handbook of Pest Control, 10th edition. GIE Media, Inc.,Valley View, OH. 1599 pp.

- Toyama GM, Kitaguchi GE, Dceda JK. 1986. A cockroach infestation survey of high, medium, and low income homes in Hawaii. Bulletin of the Society of Vector Ecologists 11: 268-270.

- Tsai TJ, Chi H. 2007. Temperature-dependent demography of Supella longipalpa (Blattodea: Blattellidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 44: 772-778.

- Wirtz RA. 1980. Occupational allergies to arthropods - documentation and prevention. Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America 26: 356-360.

- Zimmerman EC. 1948. Insects of Hawaii. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu. 2: 84-96.