common name: corn blotch leafminer

scientific name: Agromyza parvicornis Loew (Insecta: Diptera: Agromyzidae)

Introduction - Distribution - Description and Life Cycle - Host Plants - Economic Importance - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

The corn blotch leafminer, Agromyza parvicornis Loew, was originally called the "corn-leaf blotch miner" by Phillips (1914). Larvae of this fly are a minor and sporadic pest of corn.

Distribution (Back to Top)

This insect is probably distributed throughout the U.S. It has been reported as far north as Wisconsin, east to Washington, D.C. and New England, south to Alabama and Florida, and west to Salt Lake City, Utah, and Texas (Phillips 1914). It has also been reported in Quebec and Ontario, Canada (Zhu et al. 2004).

Description and Life Cycle (Back to Top)

This species can complete its life cycle in three to six weeks, depending on the time of year. Phillips (1914) reported it to have four to five generations a year. Overwintering as maggots or pupae in soil, the adults emerge in the spring to begin the life cycle again.

Eggs: The eggs are milky white and flattened along their sides, with no markings on the outer surface. Averaging nearly 0.5 mm in length and 0.18 mm in width, one end is pointed while the other is broadened (Phillips 1914). Female flies deposit eggs within leaves by inserting the ovipositor and pushing back a strip of epidermis, then bringing back the flap after depositing the egg. Eggs may be deposited into both upper and lower leaf surfaces. Females may produce 100 or more eggs during their life span. Larvae emerge from eggs in three to five days, depending upon the time of year.

Larvae: The larvae or maggots are green to white in color when they emerge from the egg. Maggots become more yellowish-white and grow to 3 mm long and 1 mm wide at maturity. The outer surfaces of the light-colored larvae are covered with closely placed punctures with a minute hair in each of them. The black-colored mouth parts are hardened by chitin and are completely retractable within the head of the maggot.

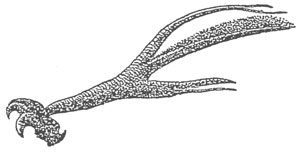

Figure 1. Mouth hooks removed from the head of a larva. From Phillips 1914.

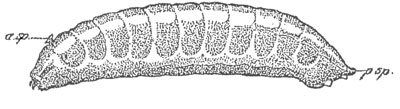

Insects breathe through small holes along the sides and ends of their bodies called spiracles. The spiracles at the front end of the maggots (anterior spiracles) are small and only slightly darker than the body color. The end of the larval body is flattened with a pair of closely-spaced spiracles (posterior spiracles) imbedded in the tissue. A sucker-like foot pad used for movement within the leaf is located near the end of the body on its lower surface (Phillips 1914).

Figure 2. Larva showing the positions of anterior (asp) and posterior (psp) spiracles. From Phillips, 1914.

Figure 3. Larva of the corn blotch leafminer, Agromyza parvicornis Loew. Photograph by James Kalisch, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

After emerging from their eggs, the maggots tunnel into corn leaves by scraping away the green leaf tissue between the leaf surfaces with their hardened mouth hooks. As they continue to feed, they leave behind the transparent tunnels or mines. These mines may grow in width as maggots grow resulting in a blotchy appearance. Often many larvae are observed feeding within a single leaf. The maggots complete development in four to 10 days or more depending upon the time of year.

Figure 4. Damage symptom (blotch) on corn produced by larva of the corn blotch leafminer, Agromyza parvicornis Loew. Photograph by Frank Peairs, Colorado State University; www.forestryimages.org.

Pupae: Mature maggots pupate either in the leaf mines or drop off the plant and pupate in the soil within a reddish-brown puparium that they form within the body of the last instar maggot. The puparium is nearly 3 mm in length and 1 mm in width with well differentiated segments, protruding anterior spiracles, and closely placed posterior spiracles (Phillips 1914). Adults emerge from the puparia in 14 to 22 days depending on the time of year.

Figure 5. Pupae of the corn blotch leafminer, Agromyza parvicornis Loew. Photograph by Juan M. Alvarez, University of Idaho.

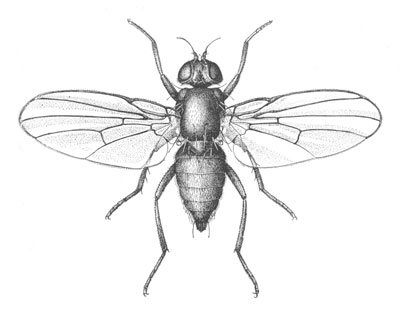

Adults: The adults are tiny gray to brown-colored flies about 6 mm long. Their wings are slightly grayish at their base and clear on the ends. The adults start depositing eggs within five to 10 days after emerging from their puparium.

Figure 6. Adult corn blotch leafminer, Agromyza parvicornis Loew. Drawing by Phillips, 1914.

Host Plants (Back to Top)

The most common host of corn blotch leafminer is corn, but it has also been reported to develop on grassy weeds, such as barnyardgrass, Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) and crabgrass, Panicum sanguinale L. (Phillips 1914).

Economic Importance (Back to Top)

This fly usually causes little or no damage of economic importance. However, large populations of this insect have occassionally resulted in economic losses in north and central Florida (Nuessly et al. 2006). Corn growers in New Mexico (Cotton City, Hidalgo County) attributed a 50% loss to this pest in 2003 (Sutherland 2005). The leaf mining seldom consumes a large enough proportion of the leaf to result in damage and normally only lower leaves are attacked. Feeding and egg depositing punctures by adults also do not have much effect on plant vitality.

Management (Back to Top)

Chemical control. No chemicals are currently registered for the management of this insect. Chemical control of maggots is difficult as they are protected within the mines. Significantly less leaf injury was reported in the early part of plant growth in plots where corn seeds were treated with both clothianidin and an in-furrow application of fipronil compared to plots where only fipronil was applied (R.C. Seymour, personal communication).

Biological control. Tiny, parasitic Hymenopteran wasps provide some control by attacking larvae within the leaf mines. It was hypothesized that lower beneficial wasp numbers resulted in higher numbers of corn blotch leaf miners in corn in 1995 in Nebraska, as well as Idaho in 2002 (Alvarez et al. 2002, Wright 2006). Among the parasitoids known (Capinera 2001) to affect this insect are:

- Hymenoptera: Eulophidae:

- Achrysocharella diastatae (Howard) and A. punctiventris (Crawford)

- Chrysocharis ainslei Crawford and C. parksi Crawford

- Cirrospilus flavoviridis Crawford

- Closterocerus tricinctus (Ashmead) and C. utahensis Crawford

- Diglyphus begini (Ashmead), D. pulchripes (Crawford), and D. websteri Crawford

- Notanisomorpha ainslei Crawford

- Zagrammosoma multilineatum (Ashmead)

- Hymenoptera: Braconidae:

- Opius diastatae (Ashmead), O. succineus Gahan, and O. utahensis (Gahan)

Selected References

- Alvarez JM, Harding G, Findlay R. 2002. Identifying the corn blotch leaf miner. Current Information Series, University of Idaho. CIS 1078.

- Capinera JL. 2001. Handbook of Vegetable Pests. Academic Press, San Diego. 729 p.

- Nuessly GS, Pernezny K, Stansly P, Sprenkel R, Lentini R. (2006). Florida Corn Insect Identification Guide. http://erec.ifas.ufl.edu/fciig (25 September 2012).

- Phillips WJ. 1914. Corn-leaf blotch miner. Journal of Agricultural Research 2: 15-31.

- Sutherland C. 2005. Insect detection, evaluation and prediction committee report on New Mexico insects. Minutes of the 53rd Annual Meeting of Southwestern Branch of Entomological Society of America. 28 February – 3 March, 2005. Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- Wright RJ. (2006). Corn blotch leafminer. NebGuide. http://www.ianrpubs.unl.edu/epublic/live/g1635/build/g1635.pdf (16 May 2008).

- Zhu X, Reid LM, Woldemariam T, Tenuta A, Lachance P. 2004. Survey of corn diseases and pests in Ontario and Québec in 2003. Canadian Plant Disease Survey 84: 1-136.