common name: whitefringed beetles

scientific name: Naupactus (=Graphognathus) spp. (Insecta: Coleoptera: Curculionidae)

Introduction - Distribution - Description - Biology - Host Plants - Survey and Detection - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

Naupactus leucoloma Boheman, the whitefringed beetle, was first collected in North America near Svea, Florida in 1936 (Buchanan 1939). This species and two others (N. minor (Buchanan)) and N. peregrinus (Buchanan)) comprise the whitefringed beetle complex in North America (Buchanan 1947, Warner 1975). Whitefringed beetles are considered serious pests of many agricultural crops (Young et al. 1950) and have become pests of young pines planted on converted croplands in the South.

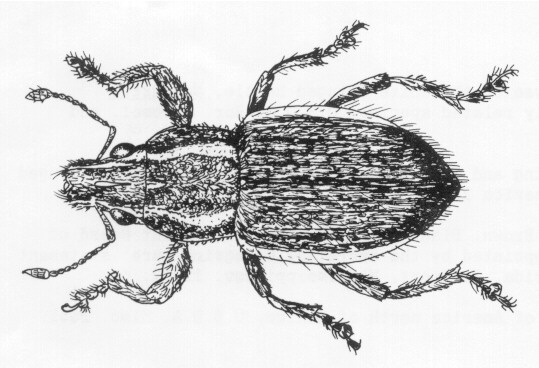

Figure 1. Dorsal view of an adult female whitefringed beetle, Naupactus sp. Photograph by: University of Florida.

Distribution (Back to Top)

Originally from South America (Argentina, Peru, Chile, Uruguay), whitefringed beetles are now widely distributed throughout the southern United States (AL, AK, FL, GA, LA, MO, MS, NC, SC, TN, TX, VA) and occur in New Zealand (Buchanan 1939, 1947; Warner 1975).

Description (Back to Top)

Adult: Female (males unknown) light to dark gray or brown, with a lighter band along the outer margins of the wing covers, and two paler longitudinal lines on each side of the thorax and head, one above and one below the eye; length ca. 12 mm. Flightless; underwings rudimentary, inner margins of outer wings fused together.

Figure 2. Adult female whitefringed beetle, Naupactus sp. (After Buchanan.)

Figure 3. Lateral view of an adult female whitefringed beetle, Naupactus sp. Photograph by: James L. Castner, University of Florida.

Egg: About 0.9 mm long X 0.6 mm wide; newly laid egg white, turning light yellow after four to five days.

Larva: Mature larva about. 12 mm long; creamy yellowish-white; C-shaped with a strong thoracic swelling.

Figure 4. Larva of a whitefringed beetle, Naupactus sp. Photograph by: Wayne N. Dixon, Division of Plant Industry.

Pupa: About 12 mm long; color creamy-white (Buchanan 1939, Young et al. 1950, Anderson 1938).

Biology (Back to Top)

Adult beetles (univoltine = one generation per year) emerge from the soil from May to October and feed on foliage. Oviposition (parthenogenetic reproduction) occurs five to 25 days after emergence. Egg masses (11 to 14 eggs) are laid on plant stems, roots, soil, and where they contact the soil onto hay, firewood, lumber, and farm tools and machinery. Eggs hatch 11 to 100+ days after oviposition (summer eggs average 17 days; winter eggs average 100 days). Larvae feed on roots, tubers, and underground stems as well as dead plant material and complete their development in the soil. Whitefringed beetles overwinter as larvae.

Pupation occurs from late April to late July in cells constructed by the larvae; however, some larvae spend a second year feeding on plants in the soil before they pupate. Most pupal cells are 5 to 15 cm below the soil surface; however, cells have been found at a depth of 36 cm. In the summer months, the pupal stage lasts ca. 13 days; in cooler months it is longer (Young et al. 1950).

Figure 5. Typical life cycle of and damage resulting from whitefringed beetles, Naupactus spp. Drawing: from USDA Leaflet No 550 "Controlling White-Fringed Beetles".

Host Plants (Back to Top)

Whitefringed beetles have been associated with over 385 plant species. The most common hosts are cotton, peanuts, okra, velvetbeans, soybeans, cowpeas, sweet potatoes, beans, and peas (Young et al. 1950, Johnson and Tappan 1987). Adults seem to prefer plants with large, broad, smooth leaves; larvae feed on agricrop plant roots, newly germinated acorns and nuts, and the roots of woody plants (e.g., peach, pecan, tung, willow) (Young et al. 1950) and pines.

Survey and Detection (Back to Top)

The results of root feeding by whitefringed beetle larvae can range from scattered areas of a few dead or dying plants within a field to nearly all plants being damaged. Examine roots of affected plants: larval feeding appears as small to large amounts of decortication or partial to complete removal of tap roots(s), below-ground portions of the stem, and some lateral roots. Sample for larvae during the months of August through May by removing ca. 0.3 m3/soil (ca. 15 cm deep) and sifting through soil sieves 8, 16, 24, 40-mesh/2.5 cm screens).

Management (Back to Top)

Considerable federal and state control efforts have been directed toward suppression of whitefringed beetles. Quarantine regulations were enacted soon after discovery of the beetles, yet the pests continued to spread. In 1940, ca. 409 acres of crops were damaged by whitefringed beetles in Florala, and by 1944 over 4,000 acres were damaged (Brown 1951).

Chemical: Various insecticides have been employed or tested to control whitefringed beetles (e.g., DDT (Brown 1951), carbaryl (Gross and Harlan 1975), diflubenzuron (Henzell et al. 1979), cryolite (Brown 1951), dieldrin, aldrin, and chlordane (Boutwell and Watson 1978)). Many of these are no longer legal for use, even by licensed applicators. Links to current management recommendations from the University of Florida are listed here.

Insect Management Guide for field crops and pastures

Insect Management Guide for forests and shade trees

Insect Management Guide for fruit and nuts

Insect Management Guide for ornamentals

Insect Management Guide for vegetable crops

Cultural: Practices include: (1) planting oats or other small grains, which are much less preferred by the beetles due to their fibrous root systems; (2) limiting acreage planted to summer legumes (e.g., peanuts, soybeans) and placing leguminous crops on a three to four year rotation. The persistence of whitefringed beetle populations in an area of land is noteworthy and speaks for the difficulty of achieving control. In some parts of Florida, pine plantations on converted agricrop land (particularly with soybean, peanut, cotton cropping histories) have failed, not only on land with no fallow period between agricrop and pine, but also up to three to four years after the last agricrop planting.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Anderson WH. 1938. A key to separate the larvae of the white-fringed beetle, Naupactus leucoloma Boh., from the larvae of closely related species. USDA Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine Circular E-422. 3 pp.

- Boutwell JL, Watson DL. 1978. Estimating and evaluating economic losses by white-fringed beetles on peanuts. Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America 24: 157-159.

- Brown AC. 1951. Statement of Arthur C. Brown, Plant Commissioner, State Plant Board of Florida before special study committees appointed by the secretary of agriculture: statement in re white-fringed beetle control in Florida. Gulfport, Mississippi, Nov. 15-17. 6 p.

- Buchanan LL. 1939. The species of Pantomorus of America north of Mexico. USDA Miscellaneous Publications 341: 1-39.

- Buchanan LL. 1947. A correction and two new races in Graphognathus (white-fringed beetles) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Journal of the Washington Academy of Science 37: 19-22.

- Gross HR, Jr, Harlan DP. 1975. Evaluation of preventive adulticide treatments for control of whitefringed beetles. Journal of Economic. Entomology 68: 366-368.

- Henzell RF, Lauren DR, East R. 1979. Effect on the egg hatch of white-fringed weevil (Graphognathus leucoloma) of feeding lucerne (Medicago sativa) treated with the insect growth regulator diflubenzuron. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 22: 197-200.

- Johnson F, Tappan WP. 1988. Field crops and pastures. pp. IV D-1-25 in 1988 Florida Insect Control Guide. Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida.

- Warner RE. 1975. New synonyms, key, and distribution of Graphognathus, whitefringed beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), in North America. USDA Cooperative Economic Insect Report 25: 855-860.

- Young HC, App BA, Gill JB, Hollingsworth HS. 1950. White-fringed beetles and how to combat them. USDA Circular 850: 1-15.