common name: yellow-legged hornet (suggested common name)

scientific name: Vespa velutina (Lepeletier, 1836) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Vespidae)

Introduction - Distribution - Description - Life Cycle and Biology - Predatory Strategies - Economic Importance - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

The yellow-legged hornet, Vespa velutina (Lepeletier) (Figure 1), is a pest of concern outside of its native range. Vespa velutina is native to Southeast Asia (Monceau et al. 2014) and has invaded several European regions, first appearing in France in 2004 (Monceau et al. 2014). As a generalist predator, they are a pest of honey bees and a major concern to many beekeepers. Vespa velutina has not been intercepted in North America, but it is believed to have high invasion potential.

Figure 1. Vespa velutina (Lepeletier), feeding on nectar. Photograph by Karine Monceau, from Monceau et al. 2014. Used with permission.

Distribution (Back to Top)

Vespa velutina is native to Asia, occurring in Korea (Monceau et al. 2014), Japan (Kishi and Goka 2017), and China (Robinet et al. 2016). It was introduced to France in 2004, most likely through the importation of bonsai pots (Robinet et al. 2016). This species has very high invasion potential and has easily spread to other European regions (Figure 2) such as Italy (Bertolino et al. 2016), Great Britain (Budge et al. 2017), the Balearic Islands (Leza et al. 2017) and northern Germany (Husemann et al. 2020).

Figure 2. Distribution of Vespa velutina (Lepeletier) in Europe up to the year 2018. Figure by Daniela Laurino. Used with permission.

Description (Back to Top)

Vespa velutina (Figures 3 and 4) adults are approximately 22 mm in length, roughly the length of a U.S. nickel. According to Monceau et al. (2014), the black and yellow coloration of Vespa velutina can be used to differentiate it from similar wasps, such as the European species Vespa crabro (Linnaeus). Monceau et al. (2014) also notes that males and females of Vespa velutina can be differentiated from each other by their antennae, with female antennae appearing thinner and shorter in length compared to those of male wasps. As with all Hymenoptera, females have a stinger and males do not. Distinguishing between queens and workers proves more difficult, with wing characteristics being the best morphological characters to use (Monceau et al. 2014).

Figure 3. Adult female Vespa velutina (Lepeletier), dorsal view. Photograph by Oliver Keller and Krystal Ashman, University of Florida.

Figure 4. Adult female Vespa velutina (Lepeletier), dorsal view. Photograph by Oliver Keller and Krystal Ashman, University of Florida.

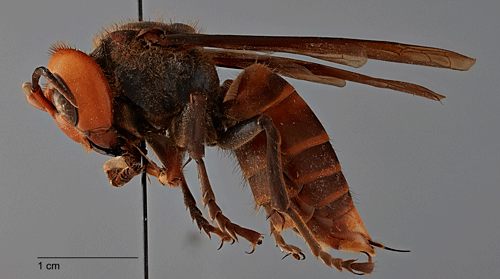

Vespa velutina is not to be confused with its close relative Vespa mandarinia (Smith) (Figures 5 and 6), a larger species native to Asia that also feeds on honey bees. Vespa mandarinia can be easily differentiated from Vespa velutina by its larger size (up to approximately 45 mm for workers) and the bright orange color of its head. Vespa velutina may also be confused with Sphecius speciosus (Drury), a large wasp found in North America known as the cicada killer. Sphecius speciosus can easily be distinguished by the yellow markings on its abdomen (Figure 7).

Figure 5. Adult female Vespa mandarinia (Smith), dorsal view. Photograph by Oliver Keller and Krystal Ashman, University of Florida.

Figure 6. Adult female Vespa mandarinia (Smith), lateral view. Photograph by Oliver Keller and Krystal Ashman, University of Florida.

Figure 7. Adult Sphecius speciosus (Drury), dorsal view. Photograph by Oliver Keller and Krystal Ashman, University of Florida.

Life Cycle and Biology (Back to Top)

The life cycle of Vespa velutina begins with a lone/single queen forming a nest (Figures 8 and 9), laying eggs, and waiting for workers to emerge (Monceau et al. 2014). Nests may be built in a variety of locations, including (but not limited to) bushes, shrubs, treetops, and building rooftops. The nest grows larger during the growing seasons (from spring to autumn), reaching around 6,000 individuals on average (Monceau et al. 2014). Colony growth is usually achieved by the construction of secondary nests (Herrera et al. 2019). Queens become active around March, laying eggs around April, and workers become active in June. Increased predation of honey bee colonies occurs by the wasps in the summer months, and mating of queens and males ensues in the later months of the year (Monceau et al. 2014) (Figure 10). The Vespa velutina life cycle is annual and all workers and males die at the end of the season. New nests are constructed by founder queens at the beginning of each year (Herrera et al. 2019).

Figure 8. Primary nests of Vespa velutina (Lepeletier) on shed ceiling represented by numbers 2 and 3. Numbers 1 and 4 represent nests of Polistes dominula (Christ). Photograph from Monceau et al. 2014. Photograph by Mr. Jacques Tardits.

Figure 9. Secondary nest of Vespa velutina (Lepeletier). Photograph by Karine Monceau, from Monceau et al. 2014.

Figure 10. Life cycle of Vespa velutina (Lepeletier) in France. Illustration from Monceau et al. 2014.

Predatory Strategies (Back to Top)

Vespa velutina is a predatory wasp that feeds on a variety of arthropods as a source of protein. It is known to be an opportunistic feeder, even feeding on decaying animals (Monceau et al. 2014).This species happens to prefer honey bees, with Apis mellifera (Linnaeus) proving to be an easier target compared to other Apis species.

Economic Importance (Back to Top)

Vespa velutina poses a major threat to the beekeeping industry, particularly that of Apis mellifera, because it reduces honey bee productivity by preying on individuals (Robinet et al. 2016). So far only few estimates are available, but some reports from Europe mention up to 30% of honey bee hives being weakened by attacks and approximately 5% can be completely destroyed (Monceau et al. 2014). The damage Vespa velutina inflicts on the beekeeping industry can be economically important because honey bees produce honey and several other important resources such as pollen, propolis, and wax. From a human health perspective, it has been noted that wasp stings in general have associated health risks because they can incite allergic reactions (Robinet et al. 2016).

Management (Back to Top)

Many management tactics have been proposed to control Vespa velutina, including using broad spectrum insecticides (Poidatz et al. 2018), hunting for nests and trapping adult wasps (Turchi and Derijard 2018), and installing baited traps (Rojas-Nossa et al. 2018). Some have proposed the use of natural enemies such the conopid fly Conops vesicularis (Darrouzet et al. 2015) and the mermithid nematode Pheromermis sp. (Villemant et al. 2015) as biological control agents.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Morgan Byron and two other anonymous reviewers for reviewing this article while providing meaningful feedback and constructive suggestions.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Bertolino S, Lioy S, Laurino D, Manino A, Porporato M. 2016. Spread of the invasive yellow-legged hornet Vespa velutina (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in Italy. Applied Entomology and Zoology 51: 589-597.

- Budge G, Hodgetts J, Jones EP, Ostoja-Starzewski JC, Hall J, Tomkies V, Semmence N, Brown M, Wakefield M, Stainton K. 2017. The invasion, provenance and diversity of Vespa velutina Lepeletier (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in Great Britain. PLoS ONE 12: e0185172.

- Darrouzet E, Gévar J, Dupont S. 2015. A scientific note about a parasitoid that can parasitize the yellow-legged hornet, Vespa velutina nigrithorax, in Europe. Apidologie 46: 130-132.

- Dong S, Wen P, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Cheng Y, Tan K, Nieh J. 2018. Olfactory eavesdropping of predator alarm pheromone by sympatric but not allopatric prey. Animal Behaviour 141: 115-125.

- Herrera C, Marqués A, Leza MM. 2019. Analysis of the secondary nest of the yellow-legged hornet found in the Balearic Islands reveals its high adaptability to Mediterranean isolated ecosystems. In Veitch CR, Clout MN, Martin AR, Russell JC, West CJ. (eds.) Island invasives: Scaling up to meet the challenge, Occasional Paper SSC 62. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. pp. 375-380.

- Husemann M, Sterr A, Maack S, Abraham, R. 2020. The northernmost record of the Asian hornet Vespa velutina nigrithorax (Hymenoptera, Vespidae). Evolutionary Systematics 4: 1-4.

- Kishi K, Goka K. 2017. Review of the invasive yellow-legged hornet, Vespa velutina nigrithorax (Hymenoptera: Vespidae), in Japan and its possible chemical control. Applied Entomology and Zoology 52: 361-368.

- Leza M, Miranda MA, Colomar V. 2017. First detection of Vespa velutina nigrithorax (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) in the Balearic Islands (Western Mediterranean): A challenging study case. Biological Invasions 20: 1643-1649.

- Monceau K, Bonnard O, Thiéry D. 2014. Vespa velutina: A new invasive predator of honeybees in Europe. Journal of Pest Science 87: 1-16.

- Poidatz J, Plantey RL, Thiéry D. 2018. Indigenous strains of Beauveria and Metharizium as potential biological control agents against the invasive hornet Vespa velutina. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology 153: 180-185.

- Robinet C, Suppo C, Darrouzet E. 2016. Rapid spread of the invasive yellow-legged hornet in France: The role of human-mediated dispersal and the effects of control measures. Journal of Applied Ecology 54: 205-215.

- Rojas-Nossa SV, Novoa N, Serrano A, Calviño-Cancela M. 2018. Performance of baited traps used as control tools for the invasive hornet Vespa velutina and their impact on non-target insects. Apidologie 49: 872-885.

- Turchi L, Derijard B. 2018. Options for the biological and physical control of Vespa velutina nigrithorax (Hym.: Vespidae) in Europe: A review. Journal of Applied Entomology 142: 553-562. Villemant C, Zuccon D, Rome Q,

- Muller F, Poinar Jr. GO, Justine J-L. 2015. Can parasites halt the invader? Mermithid nematodes parasitizing the yellow-legged Asian hornet in France. PeerJ 3: e947.