common name: crab louse

scientific name: Pthirus pubis (Linnaeus) (Insecta: Phthiraptera (=Anoplura): Pediculidae)

Introduction - Synonymy - Hosts and Distribution - Biology and Morphology - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

Sucking lice are small wingless external parasites that feed on blood. Three types of sucking lice infest humans: the body louse, Pediculus humanus humanus Linnaeus, also known as Pediculus humanus corporis; the head louse, Pediculus humanus capitis De Geer; and the crab louse or pubic louse, Pthirus pubis (Linnaeus).

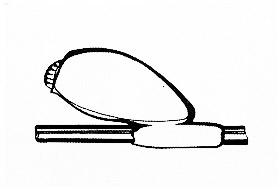

Figure 1. Head louse (left) and crab louse (right). Drawing by Division of Plant Industry.

The head louse and the body louse are morphologically indistinguishable, but are easily distinguished from the crab louse. The crab louse usually infests the hairs of the pubic and perineal regions, but may move to the armpits, beard, or mustache. It occurs rarely on the eyelids and in a few instances has been found in all stages on the scalp of unusually hairy individuals. It is relatively immobile when on the host, remaining attached and feeding for hours or days on one spot without removing its mouth parts from the skin.

Although they are irritating pests, crab lice are not known to be vectors of human diseases, whereas body lice and head lice are known to be vectors of at least three human diseases: epidemic or louse-borne typhus, caused by Rickettsia prowazeki de Rocha-Lima; trench fever, caused by Rochalimaea quintana (Schmincke) Krieg (long known as Rickettsia quintana); and louse-borne relapsing fever, caused by Borrellia recurrentis (Lebert) Bergy et al. (PAHO 1973).

Crab lice most commonly inhabit adults and are not found on children prior to puberty. Infestation with crab lice is said to result most often from contact during coitus. As with body lice and head lice, but less so with crab lice, transmission may occur from crowding of infested clothing with uninfested clothing in locker rooms and gymnasiums, by sleeping in infested beds, or from contact with badly infested persons in a crowd. Pubic lice tend to remain on their hosts throughout their lives unless dislodged, taken off with clothing, or controlled.

Little is known about the incidence of infestation with Pthirus in a human community, but generally it seems to be much lower than with Pediculus. Humans differ in their sensitivity to the bite of Pthirus. To most, it causes less irritation than that of Pediculus humanus, but some experience severe pruritus. The consequent scratching produces a localized eczematous condition of the pubic or axillary regions. "Blue spots" which may result from the bite of the crab louse are 0.2 to 3.0 cm in diameter, with an irregular outline, are painless, do not disappear on pressure, and appear to be in the deeper tissues. They appear some hours after the crab louse has bitten and last for several days (Buxton 1947). This bluish-gray discoloration of the skin, due to poisonous saliva injected by the crab louse, is similar to the melanoderma caused by the body louse (Riley and Johannsen 1938).

Louse eggs are usually referred to as nits.

Synonymy (Back to Top)

- 1758. Pediculus pubis Linnaeus, Systema Naturae, Edition 10: 611.

- 1815. Pthirus inguinalis Leach, Edinburgh Encyclopaedia 9: 77.

- 1816. Pediculus ferus von Olfers, De vegetativis et animatis corporibus in corporibus animatis reperiundis commentatius, p. 83. (Definitely a synonym of Pthirus pubis (Linnaeus).)

- 1904. Pthirus pubis (Linnaeus), Enderlein, Zoologischer Anzeiger 28: 136.

- 1918. Phthirus pubis (Linnaeus), Nuttall, Parasitology 10: 383.

- 1935. Phthirus pubis (Linnaeus), Ferris, Contributions toward a monograph of the sucking lice, part 8: 603.

- 1935. Pthirus chavesi Escomel and Velando, Cronicas de Medicina (Lima, Peru) 52: 335.

- 1936. Phthirus pubis (Linnaeus), Bedford, Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Science and

Animal Medicine 7: 105.

- 1939. Phthirus pubis (Linnaeus), Buxton, The Louse, p. 93.

Hosts and Distribution

The crab louse occurs in many parts of the world and is almost exclusively a parasite of man. Ferris (1951) noted that it had been recorded from a chimpanzee from the French Congo.

Biology and Morphology (Back to Top)

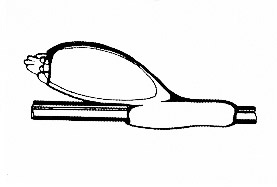

Most of what is known of the biology of Pthirus is due to two authors (Nuttall 1918, Payot 1920) who confined small numbers beneath a stocking or in a small enclosure on the skin and observed them daily. From these studies the complete life history was obtained. A quantitative knowledge of the biology of Pthirus is still unavailable. In general, the biology of Pthirus and Pediculus are similar. Buxton (1947) gave a brief account of the biology of Pthirus. He indicated that the egg resembles that of Pediculus, but is smaller. The mass of cement which secures the egg to the hair is larger in Pthirus, and its shape is somewhat different.

Figure 2. Crab louse egg (left); body louse egg (right). Drawing by Division of Plant Industry.

The female lays two to three whitish eggs during a 24 hour period. Each female may lay 15 to 50 eggs over her lifetime. The eggs hatch within six to eight days. The first instar nymphs feed for about five to six days before molting. The second instar is completed within nine to ten days and the third instar takes about 13 to 17 days. The mature adults live for about 15 to 25 days.

Neither nymphs nor adults move about very much. While feeding a crab louse grabs human hairs with at least one of its second or third legs which are adapted for this purpose. Lice do move about slowly after molting. The louse inserts its mouth parts into the skin of the host, and takes blood intermittently for many hours. Neither larvae nor adults can survive more than twenty-four hours without feeding. Nymphs resemble adults, and metamorphosis is incomplete.

Figure 3. Crab louse, Pthirus pubis (Linnaeus). Photograph by University of Florida.

The crab louse may be distinguished readily from the body louse or head louse by the following: forelegs delicate, with long, slender claws; other legs very stout, with short, stout claws: thumblike process of tibia short and stout; abdomen very short and broad; segments 1 to 5 closely crowded, thus the stigmata of segments 3 to 5 apparently lying in one lateral process. All legs of the body louse or head louse are stout; thumblike process of tibia very long and slender, bearing strong spines, forelegs stouter than the others; abdomen elongate, segments without lateral processes.

Management (Back to Top)

The presence of eggs (nits) is the most important indication of a problem because they are inactive and easier to see, whereas the lice are near the skin feeding.

Delousing methods practiced for many years prior to and during the early part of World War II were cumbersome and usually expensive. Methyl bromide, a fumigant which would destroy all stages of the louse, was developed in the interval between the two World Wars, but was found to be dangerous.

Usually treatments effective against head lice are also effective against crab lice. The liquid or powder must be applied to the pubic and anal regions of the body, underarms, and wherever the body is hairy. In particularly hairy persons, the lousicide should be applied from neck to foot, perhaps also to eyebrows and beard. The material should be well distributed and should reach the skin.

Over-the-counter preparations containing insecticides are normally used for treatment. Detailed instructions are on the label and usually require about two applications over a week. This is due to the six to eight day hatching period of the eggs. Two applications over this time usually ensure that all the adults and nymphs are killed. Contact with an infested person usually will require retreatment.

Insect Management Guide for human lice

Adequate sanitation, including frequent changes of clothing, and laundering of clothing and bedding in hot water, or dry cleaning, may be effective for decontamination of these articles, but lousicides must be used to control lice on human hosts because lice are not killed by ordinary shampoos or bathing.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Anonymous. 1975. Basic information about human lice. Pharmecs Div., Pfizer Inc., New York, New York. 12 p.

- Borror DJ, Triplehorn CA, Johnson NF. 1989. An Introduction to the Study of Insects. 6th Ed. Harcourt Brace, New York. 875 p.

- Bosik JJ, et al. 1997. Common names of insects and related organisms (1997 revision). Entomological Society of America, Special Publication

- Buxton PA. 1947. The Louse. An Account of the Lice Which Infest Man, Their Medical Importance and Control. 2nd ed. Edward Arnold & Co., London.

- Clay T. 1973. Phthiraptera. In: K.G.V. Smith (ed.), Insects and Other Arthropods of Medical Importance. British Museum (Natural History), London. 561 p.

- Ferris GF. 1951. The Sucking Lice. San Francisco: Pacific Coast Entomological Society Memorandum 1. 320 p.

- Furman DP, Catts EP. 1970. Manual of Medical Entomology. 3rd ed. National Press Books, Palo Alto, California. 163 p.

- Hase A. 1931. Siphuncalata; Anoplura; Aptera; Lause. In: Schulze (ed.), Biologie der Tiere Deutschlands 30: 1-58.

- Herms WB, James MT. 1961. Medical Entomology. The Macmillan Co., New York. 616 p.

- Horsfall WR. 1962. Medical Entomology. Arthropods and Human Disease. The Ronald Press Co., New York. 467 p.

- Martini E. 1923. Lehrbuch der medizinischen Entomologie. Gustav Fischer, Jena. 462 p.

- Mallis A. (ed.) Handbook of Pest Control. 7th Edition. Franzak & Foster Co. Cleveland. 1990. 1152 p.

- Nuttall GHF. 1918. The biology of Phthirus pubis. Parasitology 10: 383-405.

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). 1973. The control of lice and louse-borne diseases. Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Control of Lice and Louse-borne Diseases, Washington, D.C., 4-6 December 1972. World Health Organization, Washington, D.C. Scientific Publication 263. 311 p.

- Patton WS, Cragg FW. 1913. A Textbook of Medical Entomology. Christian Literature Society for India, London, Madras & Calcutta. 763 p.

- Payot F. 1920. Contribution a l'etude du Phthirus pubis (Linne, Leach). Bull. Soc. vaud. Sci. nat. 53: 127-161.

- Richards OW, Davies RG. 1977. Imms' General Textbook of Entomology. 2 vol. 10 ed. John Wiley & Sons, New York. 1354 p.

- Riley WA, Johannsen OA. 1938. Medical Entomology. A Survey of Insects and Allied Forms which Affect the Health of Man and Animals. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York. 483 p.

- Roy DN, Brown AWA. 1954. Entomology (Medical & Veterinary) Including Insecticides & Insect & Rat Control. 2nd ed. Excelsior Press, Calcutta, India. 413 p.

- Smart J. 1965. A Handbook for the Identification of Insects of Medical Importance. 4th ed. British Museum (Natural History), London. xiii + 303 p.

- Weems Jr HV, Smith CN. 1977. Human lice (Anoplura: Pediculidae), their detection and control. Div. Plant Industry, Florida Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services Entomology Circular 175. 2 p.