common name: cecropia moth, cecropia silkmoth, robin moth

scientific name: Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae: Attacini)

Introduction - Synonymy - Distribution - Description and Life Cycle - Hosts - Economic Importance - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

The cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus, is among the most spectacular of the North American Lepidoptera. It is a member of the Saturniidae, a family of moths prized by collectors and nature lovers alike for their large size and extremely showy appearance.

Figure 1. Adult female cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus, laying eggs on host plant. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Adults are occasionally seen attracted to lights during spring and early summer, a common habit of many moths. It is unclear exactly why these insects visit lights, although a number of theories exist. One such theory posits that artificial lights interfere with the moths' internal navigational equipment. Moths, and indeed many other night-flying insects, use light from the moon to find their way in the dark of night. Since the moon is effectively at optical infinity, its distant rays enter the moth's eye in parallel, making it an extremely useful navigational tool. A moth is confused as it approaches an artificial point source of light, such as a street lamp, and may often fly in circles in a constant attempt to maintain a direct flight path.

Synonymy (Back to Top)

Hyalophora Duncan, 1841

- Samia. - auct. (not Hübner, [1819])

- Platyysamia Grote, 1865

cecropia (Linnaeus, 1758)

- diana (Castiglioni, 1790)

- macula (Reiff, 1911)

- uhlerii (Polacek, 1928)

- obscura (Sageder, 1933)

- albofasciata (Sageder, 1933)

- (from Heppner 2003)

Distribution (Back to Top)

The range of Hyalophora cecropia is from Nova Scotia in eastern Canada and Maine south to Florida, and west to the Canadian and U.S. Rocky Mountains.

Description and Life Cycle (Back to Top)

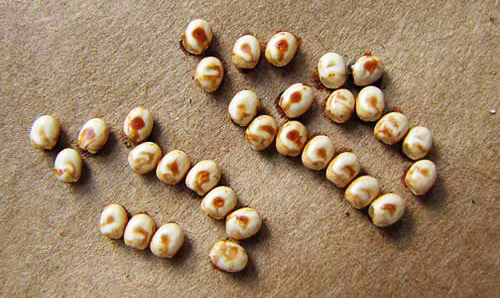

Eggs: The large and mottled reddish/brown eggs are are laid by the female on both sides of the host leaf in small groups.

Figure 2. Eggs of the cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus, laid on brown paper bag. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Larvae: There are typically five larval instars, each lasting approximately one week. First instar larvae are black and feed gregariously.

Figure 3. First instar larva of the cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus, emerging from egg. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Figure 4. First instar larvae of the cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Second instar larvae are variable from dark yellow to yellow, and also feed gregariously.

Figure 5. Second instar larvae of the cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus. Note color variation, even though they are from the same batch of eggs. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Third, fourth, and fifth instar larvae are similar in their exuberant appearance. The body is very large, with fifth instar larvae reaching up to 4.5 inches in length. Color is bright green or sea green with prominent dorsal protuberances, all with distal black spines. Thoracic protuberances are orange to red, abdominal protuberances are yellow, and side protuberances are pale blue. The larvae of the Columbia Silkmoth (H. columbia) are very similar, but have red thoracic protuberances, yellow-pink abdominal protuberances, and side protuberances which are more white than blue with black bases.

Figure 6. Third instar larva of the cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Figure 7. Fourth instar larva of the cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Figure 8. Fifth instar larva of the cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus. Although green in color, the top appears to have an irridescent pale-bluish sheen when viewed in direct light. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Pupae: The pupae are large, dark brown, and encased within a silk cocoon that is attached lengthwise along a stem or branch of the host plant or nearby plant.

Figure 9. Cocoon of the cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus, on host plant. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Figure 10. Pupa of the cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus, removed from cocoon. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Adults: Size is variable but usually quite large, with a wingspan approaching up to 6 inches. Wings are brownish with red near the base of the forewing. Crescent-shaped spots of red with whitish center are obvious on all wings, but are larger on the hindwings. All wings have whitish coloration followed by reddish bands of shading beyond the postmedial line that runs longitudinally down the center of all four wings. The body is hairy, with reddish coloring anteriorly, and fading to reddish/whitish. The abdomen has alternating bands of red and white.

Figure 11. Newly emerged adult cecropia moth, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

Figure 12. Adult cecropia moths, Hyalophora cecropia Linnaeus. Photograph by David Britton. Used with permission.

For an excellent photographic account of the Hyalophora cecropia life cycle, see Hyalophora cecropia: Changes of Color and Contrast (Britton 2009).

Hosts (Back to Top)

Plant families and species:

- Aceraceae - Acer negundo, A. rubrum, A. saccharinum, A. spicatum

- Betulaceae - Alnus serrulata, Betula alba, B. alba, B. allagheniensis, B. lenta, B. papyrifera, Corylus Americana, C. cornuta, Ostrya virginiana

- Berberidaceae - Berberis vulgaris

- Cannabidaceae - Humulus lupulus

- Caprifoliaceae - Sambucus candensis, S. pubens, Symphoricarpos albus

- Ericaceae - Gaylussacia frondosa, Vaccinium sp.

- Fagaceae - Fagus sp., Quercus alba

- Juglandaceae - Carya illinoinensis

- Lauraceae - Sassafras albidum

- Leguminosae - Gleditsia triacanthos, Wisteria sinensis

- Lythraceae - Decondon verticillatus

- Naucleaceae - Cephalanthus occidentalis

- Oleaceae - Fraxinus sp., Syringa vulgaris

- Paeoniaceae - Paeonia officinalis

- Philadelphaceae - Philadelphus inodorus

- Pinaceae - Picea sp.

- Rosaceae - Amelanchier arborea, A. arbutifolia, Crataegus calpodendron, C. crusgalli, C. oxycantha, C. pedicellata, Malus coronaria, M. pumila, Physocarpus opilifolius, Prunus cerasus, P. domestica, P. illicifolia, P. maritime, P. pensylvanica, P. serotina, P. virginiana, Pyrus communis, Rubus allegheniensis, R. idaeus, R. occidentalis, Sorbus Americana, Spiraea corymbosa, S. salicifolia, S. tomentosa

- Salicaceae - Populus balsamifera, P. tremuloides, Salix alba, S. humilis, S. lucida, S. viminalis

- Saxifragaceae - Ribes americanum, R. grossularia, R. nigrum, R. rubrum, R. sativum

- Tiliaceae - Tilia Americana, T. europaea

- Ulmaceae - Ulmus Americana, U. rubra, U. thomasii

- Vitaceae - Parthenocissus quinquefolia

- (from Heppner 2003)

Economic Importance (Back to Top)

While Hyalophora cecropia larvae are large and feed on a wide range of host plants, this species is not considered a serious pest in any parts of its range.

Some populations of Hyalophora cecropia may be in decline due to a number of factors, including nontarget effects of introduced biological control agents. Boettner et al. (2000) suggested that the generalist parasitoid fly Compsilura concinnata (Diptera: Tachinidae) may be responsible for such declines in the northeastern U.S.

Due to its size and hardiness, Hyalophora cecropia has been used extensively in physiological and biochemical research. Carroll Williams conducted pioneering work on juvenile hormone and its role in molting and metamorphosis using this species.

Owing to its impressive size and appearance, Hyalophora cecropia has become a favorite of collectors and amateur Lepidopterists. Eggs and pupae are commercially available, and a small livestock industry has developed around this and other related species.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Boettner GH, Elkinton JS, Boettner CJ. 2000. Effects of a biological control introduction on three nontarget native species of Saturniid moths. Conservation Biology 14: 1798-1806.

- Britton D. 2009. Hyalophora cecropia: A Life Cycle Photo Journal, Part 2: The Caterpillar: In Changes of Color and Contrast. A Butterfly in Transformation. (19 December 2013)

- Covell Jr CV. 1984. A Field Guide to Moths of Eastern North America. Houghton Mifflin Co. Boston, MA. 496 pp.

- Heppner JB. 2003. Lepidoptera of Florida. Arthropods of Florida and Neighboring Land Areas Vol. 17. Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, Gainesville, FL.

- Passonneau JV, Williams CM. 1953. The moulting fluid of the cecropia silkworm. Journal of Experimental Biology 30: 545-560.

- Powell JA, Opler PA. 2009. Moths of Western North America. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California. 383 pp.

- Stevenson A. 2008. Probing question: why are moths attracted to light? Research Penn State. (19 December 2013)

- Williams CM. 1952. Morphogenesis and the metamorphosis of insects. Harvey Lect. 47: 126-155.