common name: a stubby-root nematode

scientific name: Trichodorus obtusus Cobb (syn Trichodorus proximus) (Nematoda: Adenophorea: Triplonchida:

Diphtherophorina: Trichodoridea: Trichodoridae)

Introduction - Distribution - Life Cycle and Biology - Importance - Symptoms - Hosts - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

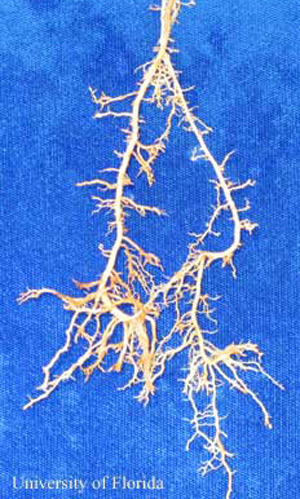

Nematodes in the family Trichodoridae (Thorne, 1935) Siddiqi, 1961, are commonly called stubby-root nematodes, because feeding by these nematodes can cause a stunted or stubby appearing root system system (Figure 1). Trichodorus obtusus is one of the most damaging nematodes on turfgrasses, but also may cause damage to other crops.

Figure 1. St. Augustinegrass roots with "stubby-root" symptoms caused by Paratrichodorus minor. Photograph by W. T. Crow, University of Florida.

Distribution (Back to Top)

Trichodorus obtusus is only known to occur in the United States. A report of Trichodorus proximus (a synonym of Trichodorus obtusus) from Ivory Coast was later determined to be a different species. Trichodorus obtusus has been reported in the states of Florida, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, New York, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, and Virginia.

Life Cycle and Biology (Back to Top)

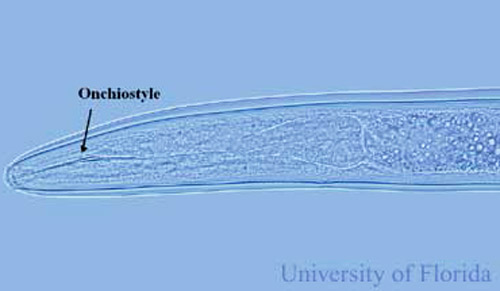

While large for a plant-parasitic nematode (about 1/16 inch long), Trichodorus obtusus is still small enough that it can be seen only with the aid of a microscope. Stubby-root nematodes are ectoparasitic nematodes, meaning that they feed on plants while their bodies remain in the soil. They feed primarily on meristem cells of root tips. Stubby-root nematodes are plant-parasitic nematodes in the Triplonchida, an order characterized by having a six-layer cuticle (body covering). Stubby-root nematodes are unique among plant-parasitic nematodes because they have an onchiostyle, a curved, solid stylet or spear they use in feeding (Figure 2). All other plant-parasitic nematodes have straight, hollow stylets. Stubby-root nematodes use their onchiostyle like a dagger to puncture holes in plant cells. The stubby root nematode then secretes from its mouth (stoma) salivary material into the punctured cell. The salivary material hardens into a feeding tube which functions as a straw enabling the nematode to withdraw and ingest the cell contents through the tube (Figure 3). After feeding on an individual cell, the stubby-root nematode will move on to feed on other cells, leaving old feeding tubes behind and forming new ones in each cell that it feeds from (Figure 4).

Figure 2. Curved onchiostyle of Trichodorus obtusus Cobb, a stubby-root nematode. Photograph by W. T. Crow, University of Florida.

Figure 3. Stubby-root nematode feeding on a root hair through a feeding tube. Photograph by Urs Wyss, Institute of Phytopathology, Germany.

Figure 4. Feeding tube left in a root hair after feeding by a stubby-root nematode. Photograph by Urs Wyss, Institute of Phytopathology, Germany.

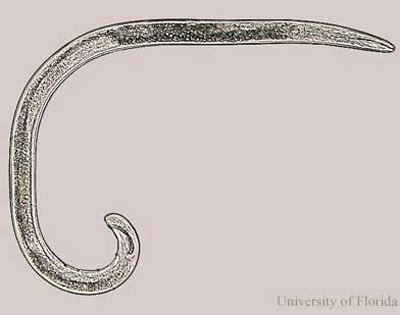

Trichodorus obtusus is an amphimictic species, meaning that males (Figure 5) and females (Figure 6) must mate to produce offspring. Therefore, in most populations there are almost as many males as females. After mating, female Trichodorus obtusus lay eggs that remain in soil until they hatch as second-stage juveniles. Stubby-root nematodes are obligate plant-parasites, meaning they must feed on plants in order to survive and reproduce. Once it locates a root and starts feeding, the juvenile nematode will molt 3 times before it becomes an egg-laying adult.

Figure 5. Male Trichodorus obtusus Cobb, a stubby-root nematode. Photograph by W. T. Crow, University of Florida.

Figure 6. Female Trichodorus obtusus Cobb, a stubby-root nematode. Photograph by W. T. Crow, University of Florida.

Importance (Back to Top)

Trichodorus obtusus is very damaging on turfgrasses. In Florida it is one of the most common nematode problems diagnosed on St. Augustinegrass lawns. By damaging the turf root system it makes the turf more prone to environmental stresses and may lead to increased use of water and fertilizer inputs. It also makes turf less competitive with weeds and may lead to increased herbicide usage.

Symptoms (Back to Top)

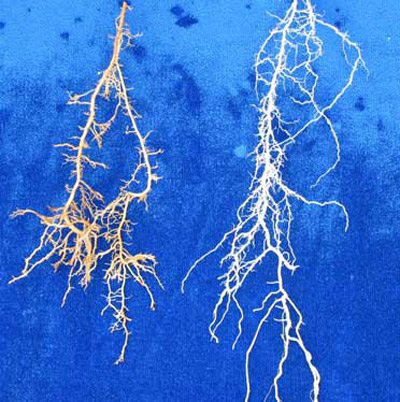

On turfgrasses, damage caused by Trichodorus obtusus usually occurs in irregularly shaped patches within a given area (Figure 7). Symptoms are usually worse in sandy than in heavier soils. The turf may wilt in these areas, thin out, and die if stresses such as drought occur (Figure 8). Roots may appear abbreviated or "stubby" looking (Figure 1). However, these symptoms can be caused by other factors, so the only way to verify if Trichodorus obtusus is a problem is to have a nematode assay conducted by a credible nematode diagnostic lab. The University of Florida Nematode Assay Laboratory provides routine diagnosis of Trichodorus obtusus, and other plant-parasitic nematodes for the public at a nominal fee.

Figure 7. Wilting patches of St. Augustinegrass resulting from a high infestation of Trichodorus obtusus Cobb, a stubby-root nematode. Photograph by W. T. Crow, University of Florida.

Figure 8. Dying patches of St. Augustinegrass resulting from a high infestation of Trichodorus obtusus Cobb , a stubby-root nematode, combined with drought stress. Photograph by W. T. Crow, University of Florida.

Hosts (Back to Top)

Known hosts of Trichodorus obtusus are: bermudagrass (Cynodon spp.), St. Augustinegrass (Stenotaphrum secundatum), zoysia grass (Zoysia spp.), and tomato (Lycopersicon esculetum). It has been associated with; big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), eucalyptus (Eucalyptus sp.), Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pretensis), rhododendron (Rhododendron sp.), saw palmetto (Sabal palmetto), potato (Solanum tuberosum), littleleaf linden (Tilia cordata), sweetbay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana), sorghum-sudangrss (Sorghum bicolor x S. arundinaceum) and seashore paspalum (Paspalum vaginatum).

Figure 9. St. Augustinegrass roots grown in soil inoculated with Trichodorus obtusus (left), a stubby-root nematode, and in non-inoculated soil (right). Photograph by W. T. Crow, University of Florida.

Management (Back to Top)

Nematicides are available for use on golf courses, sod farms, cemeteries, athletic fields, and industrial grounds. However, no effective nematicides are currently available for use on residential lawns.

See the University of Florida UF EDIS site for current nematicide recommendations.

Often, if other turf stress factors such as improper mowing, insufficient light, poor irrigation coverage, etc. can be identified, damage caused by Trichodorus obtusus can be lessened by improving these conditions. Increasing irrigation frequency also can help, but may not be practical during times of water restriction.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Crow WT. 2004. Diagnosis of Trichodorus obtusus and Paratrichodorus minor on turfgrasses in the Southeastern United States. Plant Health Progress: in press.

- Crow WT, Welch JK. 2004. Root reductions of St. Augustinegrass (Stenotaphrum secundatum) and hybrid bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon × C. transvaalensis) induced by Trichodorus obtusus and Paratrichodorus minor. Nematropica: in press.

- Decreamer W. 1991. Stubby root and virus vector nematodes. p.587-625 In Nickle WR (ed.) Manual of Agricultural Nematology. Macel Dekker, Inc. New York.

- Hunt DJ. 1993. Aphelenchida, Longidoridae and Trichodoridae: Their systematics and bionomics. CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

- Rhoades HL. 1965. Parasitism and pathogenicity of Trichodorus proximus to St. Augustinegrass. Plant Disease Reporter 49: 259-262.