common name: awl nematodes

scientific name: Dolichodorus spp. Cobb, 1914 (Nematoda: Secernentea: Tylenchida: Tylenchina: Dolichodoridae: Dolichodorinae)

Introduction and Distribution - Life Cycle and Biology - Symptoms - Hosts - Management - Selected References

Introduction and Distribution (Back to Top)

Awl nematodes were first described in 1914 from specimens collected at Silver Springs, Florida, and Douglas Lake, Michigan. Species of Dolichodorus are found worldwide, but two species, Dolichodorus heterocephalus and Dolichodorus miradvulvus, are the most common in Florida. Usually, awl nematodes are found in moist to wet soil, low areas of fields, and near irrigation ditches and other bodies of fresh water. Because these nematodes prefer moist to wet soils they rarely occur in agricultural fields and are not as well studied as many other plant-parasitic nematodes.

Life Cycle and Biology (Back to Top)

Adult awl nematodes range in length from about 1.5 mm to 3 mm, making them one of the largest plant-parasitic nematodes. Both sexes are present throughout the life cycle. Eggs hatch after 14 to 17 days. Adults and all juvenile stages feed on roots, sometimes remaining in one spot for up to a week. Awl nematodes can survive in a fallowed greenhouse pot for up to three months.

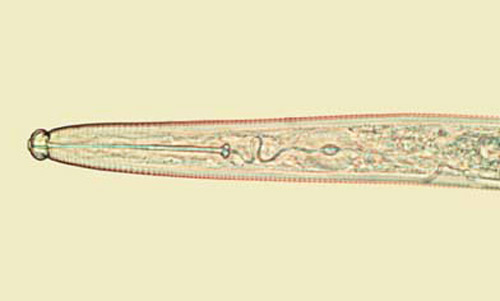

Figure 1. The head of an awl nematode in the genus Dolichodorus. Photograph by Jon Eisenback, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

An ectoparasite, awl nematode feeds on small or large roots, root tips and the hypocotyl. Twelve hours after inoculation, it feeds near the root tip. The cells there become brownish-yellow after several days, and brown lesions form. The result is tissue disorganization, root curvature and dead or dying root tips.

Symptoms (Back to Top)

The damage caused by awl nematodes leads to severe stunting of the entire plant because of depletion of the root system. The roots are often coarse with stubby tips. The few secondary roots that remain are stubby as well.

Figure 2. Awl nematodes (Dolichodorus spp.) cause severe stunting, which can be seen in the celery plant on the right. The plant on the left is unaffected. Photograph by Division of Plant Industry.

Hosts (Back to Top)

Hosts include anubius, balsam, bean, Bermudagrass, cabbage, carnation, celery, centipedegrass, corn, cotton, cranberry, hydrilla, impatiens, St. Augustinegrass, sugarcane, tomato, palms, pepper, potato and water chestnut.

Management (Back to Top)

Often awl nematodes are an indicator of excess soil moisture. In some cases improving drainage or reducing irrigation may reduce or eliminate problems with this nematode. Using soil dredged from ditches, ponds or other water sources to top-dress agricultural fields or to make planting beds may be a source of contamination with awl nematodes. When awl nematodes are present in high numbers this practice should be avoided.

For the most current recommendations for nematode management on a particular crop see the Nematode Management Guide.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Christie JR. 1959. Plant nematodes, their bionomics and control. University of Florida Agricultural Experiment Station 216 pp.

- Orton Williams KJ. 1986. Dolichodorus heterocephalus. C.I.H. Descriptions of Plant-parasitic Nematodes. Set 4, No. 56. Commonwealth Institute of Parasitology. C.A.B. International. 3 pp.

- Paracer SM. 1968. The biology and pathogenicity of the awl nematode, Dolichodorus heterocephalus. Nematologica 13:517-524.

- Perry VG. 1953. The awl nematode, Dolichodorus heterocephalus, a devastating plant parasite. Proceedings of the Helminthologia Society of Washington 20:21-27.

- Smart GC, Khoung NB. 1985. Dolichodorus miradvulvus n. sp. (Nematoda: Tylenchida) with a key to species. Journal of Nematology 17:29-37.

- Smart GC, Nguyen KB. 1991. Sting and awl nematodes. Pp. 627-668 In Nickle WR (ed.), Manual of Agricultural Nematology. Marcel Dekker Inc., NY.