common name: small carpenter bees

scientific name: Ceratina spp. (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Apidae: Xylocopinae)

Introduction - Synonymy and Taxanomy - Distribution - Identification - Biology - Economic Importance - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

In America, north of Mexico, the small carpenter bees, Ceratina, comprise one of two genera of the subfamily Xylocopinae. The other genus contains the large carpenter bees, Xylocopa. Of the 21 species of Ceratina in America north of Mexico, only two are known to occur in Florida: Ceratina cockerelli H.S. Smith, and Ceratina dupla Say.

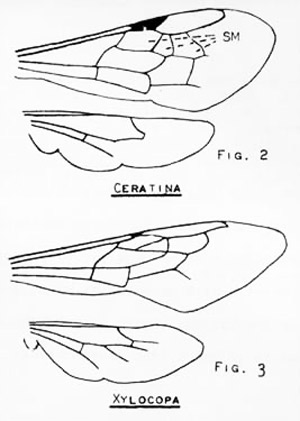

Figure 1. Differences in wing venation between the small carpenter bees, Ceratina spp., and the large carpenter bees, Xylocopa spp. Drawings by Division of Plant Industry.

Synonymy and Taxonomy (Back to Top)

Mitchell (1962) described the subspecies Ceratina dupla floridanus from Florida, but Daly (1973) synonymized it simply as a more densely punctate, and brighter blue population of the typical eastern Ceratina dupla.

At various times, carpenter bees have been placed in the families Anthophoridae, Xylocopidae or Apidae. Hurd and Moure (1963) traced the taxonomic history of these bees, with the most recent placement within Apidae (Krombein 1967). This family is characterized, in part, by the jugal lobe of the hindwing being absent or shorter than the submedian cell and by the forewing having three submarginal cells.

Distribution (Back to Top)

Ceratina cockerelli is found throughout Florida and most of the southern coastal states from Texas to Georgia (Daly 1973). Specimens have not been reported from Alabama or Mississippi, but probably occur there. Ceratina dupla is found throughout Florida as well as most of the eastern United States (Daly 1973).

Identification (Back to Top)

Within the family Apidae, carpenter bees are distinguished most easily by the triangular second submarginal cell, and by the lower margin of the eye almost in contact with the base of the mandible (i.e., the malar space is absent).

The easiest method of separating Ceratina from Xylocopa is by size: Ceratina are less than 8 mm in length whereas Xylocopa are 20 mm or larger. In addition, in Ceratina the second submarginal cell is about as high as it is wide basally, whereas in Xylocopa it is about half as high as it is wide basally.

Small carpenter bees are black, bluish green, or blue, and often have yellowish or whitish markings on the clypeus, pronotal lobes, and legs. The two Florida species of Ceratina may be separated as follows:

- Ceratina cockerelli (both sexes): body length 3 to 4.5 mm; head and thorax mostly black, abdomen black with brownish or tawny areas; head and scutum (dorsum of thorax) mostly polished, without punctures for the most part.

- Ceratina dupla (both sexes): body length 6 to 8 mm; body dark metallic blue; head and scutum with numerous distinct punctures, not polished.

Figure 2. Small carpenter bee, Ceratina dupla Say, dorsal and side views. Photograph by Division of Plant Industry.

Biology (Back to Top)

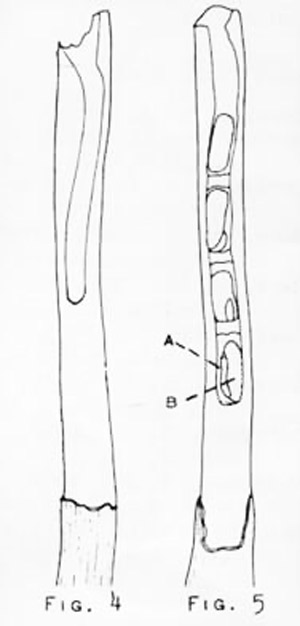

In general, members of this genus use their mandibles to excavate nests in the pith of broken or burned plant twigs and stems. Females overwinter as adults in partially or completely excavated stems. In the spring, this resting place (hibernaculum) is modified into a brood nest by further excavation. Rau (1928) reported several nests of Ceratina calcarata Robertson that ranged from 20 to 30 cm deep. Daly (1966) measured 126 nests of Ceratina dallatorreana Friese that ranged from 3 to 19 cm deep. When a desired depth is reached, the female collects pollen and nectar, places this mixture at the base of the burrow, lays an egg on the provision, and then caps off the cell with masticated plant material. Several cells are constructed end to end in each plant stem, the absolute number depending upon the depth to which the nest was excavated. Daly (1966) found a range of two to 12 cells (19 completed nests examined) for Ceratina dallatorreana.

Figure 3. Nest diagrams of the small carpenter bees, Ceratina spp. Left: overwintering nest (hibernaculum); Right: active brood nest with (A) bee larva and (B) provisions. Drawing by Division of Plant Industry.

The female works at a single stem until it is filled with cells, each of which contains provisions and an egg or larva, except for the last cell near the nest entrance. Here the bee rests and, according to Malyshev (1936) and Daly (1966), defends her nest from intruders. The female bee remains with the nest until her progeny emerge. Since the nest has been under construction for some time, the oldest progeny (at the base of the nest) mature and begin to gnaw their way out before the others above them are ready. This poses a special problem because the bees do not emerge laterally through the side of the stem, but vertically through all the other cells. Rau described this process thoroughly for Ceratina calcarata (1928).

Essentially the oldest bee chewed apart the cell cap above and packed it at the base of its own cell. If the bee above was not mature it was carefully moved down to rest on the new "floor." If the bee above was mature, the eldest passed it by and worked on the cell cap above, passing the pithy material to the younger bee or bees beneath. These bees packed the material at the base of the nest, moving and adjusting any remaining pupae. Thus the mature bees at the base of the nest gained freedom by "... a process of displacement, gradually shifting the material behind them as they make their way to the top" (Rau 1928). In the process observed by Rau, the eldest bees took eight days to make their way to the entrance; several days later, all the bees emerged.

Special biological references to the Ceratina occurring in Florida are scarce. Extensive flower visitation records were given by Mitchell (1962) and Daly (1973). The only biological record forCeratina cockerelli was given by Daly (1973) who cited Sage (in litt.) as reporting nests "... in dead, cut stems of sea-oats, Uniola paniculata L., on the beach of Mustang Island, Texas." The more important papers, though wholly inadequate, are Ashmead (1894), Comstock and Comstock (1895), and Graenicher (1905).

Economic Importance (Back to Top)

Unlike their larger relatives in the genus Xylocopa, the small carpenter bees in the genus Ceratina are not known to be of economic importance.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Ashmead WH. 1894. The habits of the aculeate Hymenoptera. I. Psyche 7: 19-26.

- Borror DJ, Triplehorn CA, Johnson NF. 1989. An Introduction to the Study of Insects. 6th Ed. Harcourt Brace, New York. 875 pp.

- Comstock JH, Comstock AB. 1895. A Manual of the Study of Insects. The Comstock Publishing Company, Ithaca, NY. p. III-VII, 1-701 (reprinted in many editions without change).

- Daly HV. 1966. Biological studies on Ceratina dallatorreana, an alien bee in California which reproduces by parthenogenesis. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 59: 1138-1154.

- Daly HV. 1973. Bees of the genus Ceratina in America north of Mexico. University of California Publications Entomology 74: 1-113.

- Graenicher S. 1905. On the habits of two ichneumonid parasites of the bee Ceratina dupla Say. Entomological News 16: 43-49.

- Grissell EE, Sanford MT. (December 2011). Large Carpenter Bees, Xylocopa spp. Featured Creatures. EENY-100. (17 June 2014)

- Malyshev SI. 1936. The nesting habits of solitary bees. A comparative study. Eos 11: 201-309, pl. III-XV.

- Mitchell TB. 1962. Bees of the Eastern United States. Vol. II. North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 152: 1-557.

- Rau P. 1928. The nesting habits of the little carpenter-bee, Ceratina calcarata. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 21: 380-397.