common name: horse bot fly

scientific name: Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer) (Insecta: Diptera: Oestridae)

Introduction - Synonymy - Distribution - Description and Life Cycle - Hosts - Veterinary Significance - Medical Significance - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

Worldwide, nine different species of Gasterophilus exist, primarily affecting horses and donkeys. Three of the more common Gasterophilus species are found in North America. Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer) is the more common horse bot fly which is an internal parasite of the gastrointestinal tract. Gasterophilus nasalis (Linnaeus), the nose bot fly, and Gasterophilus haemorrhoidalis (Linnaeus), the throat bot fly, are also distributed throughout North America.

Figure 1. Lateral view of an adult horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer). Photograph by Jerry Butler, University of Florida.

The bot flies are in the family Oestridae. Within this family are four subfamilies, including the Gasterophilinae, the stomach bot flies. All subfamilies within Oestridae are related by their larval feeding characteristics. The larvae demonstrate obligatory myiasis because they require a living host to complete development (Mullen and Durden 2002). Completion of the bot flies' life cycle is dependent on the larvae consuming nutrients from tissues in the gastrointestinal tract of the horse (Zurek 2004).

Synonymy (Back to Top)

Oestrus equi Clark, 1797

Oestrus intestinalis DeGeer 1776

Gasterophilus intestinalis De Geer 1776

(from ITIS 2007)

Distribution (Back to Top)

According to Mullen and Durden (2002), the Gasterophilinae appear to have originated in Africa. Currently, the horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis, is found throughout the world and is one of the main species present in North America. The horse bot fly directly enhances its own dispersal by traveling several miles to find an appropriate host. Dispersal also occurs during larval stages by transport of infested equines from one location to another (Zurek 2004).

Gasterophilus intestinalis and Gasterophilus nasalis are found in Florida. Although found throughout the entire state, geographical location determines seasonality of adult activity. In the southern portions of Florida, the adult fly will be more active throughout the year whereas fly activity in central and northern Florida may be limited to late spring through early winter (Kaufman et al. 2006).

Description and Life Cycle (Back to Top)

Horse bot flies undergo complete metamorphosis, including three larval instars (Merial 2001). Only one generation is produced per year. The stages of the life cycle are not restricted to certain seasons due to the varied climates found in different geographical locations. However, a general cycle begins with eggs laid in the early summer months (Pfizer 2007).

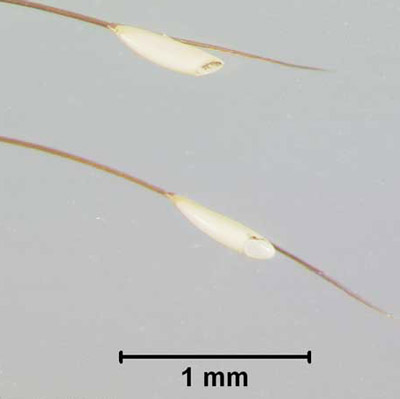

Eggs: The female bot fly can oviposit between 150 and 1000 eggs on a horse's body (DuPonte and Larish 2003). This typically occurs during the early summer months. The female oviposits directly on single hairs of the horse's front legs (cannon bone area), abdomen, flanks, and shoulders. Ovipositing on the rear legs appears to be discriminated against by most flies, whereas age, breed, size, and sex do not appear to be a factor (Cogley and Cogley 2000).

The bot fly eggs are approximately 0.05 inches (0.127 cm) in length and are pale to grayish yellow (NDSU 1991). The eggs are essentially stalk-less and are attached near the tip of the hair. The eggs contain two regions on the lower half which surround the hair allowing for attachment and another region extending at a thirty degree angle from the hair (NDSU 1991).

Figure 2. Horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer), egg case (hatched) attached to a horse hair. Photograph by Morgan McLendon, University of Florida.

Figure 3. Horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer), egg casings (hatched) attached near the tip of horse hairs. Photograph by Morgan McLendon, University of Florida.

Larvae: The eggs develop into first instar larvae within five days of being deposited by the female. Eggs hatch into a maggot within seven to 10 days of being laid. Larvae are stimulated to emerge by the horse licking or biting the attached, fully developed eggs. The larvae either crawl to the mouth or are ingested and subsequently bury themselves in the tongue, gums, or lining of the mouth and remain for approximately 28 days. After wandering in the mucosa of the mouth, the larvae molt to the second stage and move into the stomach (Merial 2001). The second and later third stage larvae typically attach to the lining of the stomach in the non-glandular portion near the junction of the esophageal and cardiac regions. The second and third instar larvae remain immobile for the following nine to 12 months (DuPonte and Larish 2003, Zurek 2004).

Figure 4. Horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer), larval infestation in the stomach of a horse. Photograph by Jerry Butler, University of Florida.

The third instar larvae are relatively large, between 1/2 to 3/4 inch (1.27 to 1.91 cm) long. They are adapted to life in the gastrointestinal tract with their rounded body, narrow, hooked mouthparts, and spines (Pfizer 2007). The hooked mouthparts (maxillae) enable the larvae to securely attach to the lining of the stomach and intestinal tract. The larvae use their flat mandibles to abrade the tissue of the stomach. The uniqueness of the spines is helpful in identifying the species. Gasterophilinae are all characterized with rows of smaller spines amongst rows of larger spines (Colwell et. al 2007). The third stage instar larva is distinguished by its yellowish color (NDSU 1991).

Figure 5. Dorsal view (head on left) of the third instar larva of the common horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis (De Geer). Photograph by Lyle Buss, University of Florida.

Figure 6. Ventral view (head on left) of the third instar larva of the common horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer). Photograph by Lyle Buss, University of Florida.

Pupae: After the third instar larvae have matured, they detach from the gastrointestinal tract and pass from the horse's body in the feces. The larvae burrow into the soil or dried manure where they pupate and remain for the next one to two months. This stage of the life cycle occurs between late winter and early spring. Because of horses' behavior to habitually defecate in the same location and the lack of larvae movement, the amount of pupae in fecal piles can become rather significant (Cogley and Cogley 2000).

Figure 7. Pupa of the common horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer). Photograph by Lyle Buss, University of Florida.

Adult: The adult horse bot fly emerges after a three to 10 week period during the summer or fall season. After the fly emerges from the pupa, it quickly finds a mate. The mating activity typically occurs in the early afternoon during warm, sunny weather in relative proximity to horses or on hilltops. According to Cogley and Cogley (2000), mating may not solely rely on the presence of horses or hilltops. Mating is likely to occur around fecal piles where pupae numbers are large thereby greatly increasing the chances of male and female contact upon adult fly emergence. Once the male and female flies meet, they sink to the ground and copulation occurs within three to four minutes. Within hours, the female begins host seeking and oviposits. Dispersal of eggs by the female is not restricted to one horse but can occur on many horses within an area. The female increases the chance of larval survival by not limiting her eggs to one horse (Cogley and Cogley 2000). The adult female lifespan lasts seven to 10 days (Williams and Knapp 1999).

The adult fly is between 2/3 and 3/4 inch (1.67 to 1.91 cm) in length and resembles a bee with its black and yellow hairs. Because it is a fly, is has only one pair of wings. The adult has small, nonfunctional mouthparts and does not feed (DuPonte and Larish 2003, Kaufman et al. 2006). The female's abdomen is elongated, curled under and serves as an ovipositor (Zurek 2004).

Figure 8. Lateral view of the adult common horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis (DeGeer). Photograph by Lyle Buss, University of Florida.

Hosts (Back to Top)

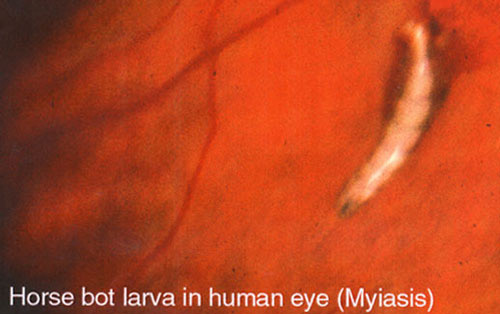

The common host of this particular species of bot fly is the horse. Other equid species, including mules and donkeys, can also serve as hosts. Although accidental, the horse bot also has been reported in man causing either ocular (eye) or cutaneous (skin) myiasis (Kaufman et al. 2006).

Veterinary Significance (Back to Top)

The horse bot fly causes indirect damage to the horse through attempts at egg laying. The dive-bombing action of the bot fly can range from a simple annoyance to severe fright among horses. Injuries may result as the horse tries to rid themselves of this hovering fly. Weight-loss may occur if the annoyance is great enough to cause the horse to stop grazing.

The direct damage the bot fly causes occurs after the larvae enter the animal's mouth and gastrointestinal tract. When the first instar larvae burrow into the mouth, the horse may experience severe irritation, as well as the development of pus pockets and loosened teeth. Loss of appetite may develop due to the larva's inhabitance (Mullen and Durden 2002).

As the second and third instar larvae inhabit the gastrointestinal tract and attach to the stomach and intestine, multiple complications may arise. Larvae present in large numbers in the stomach can cause blockages and lead to colic. According to Mullen and Durden (2002), horses are capable of tolerating an infestation of 100 larvae. Large numbers of larvae impact the host by damaging the tissue of the stomach or the gut lining and consuming the nutrients that would otherwise be beneficial to the hosts' well-being. Other health issues that may develop due to a severe infestation of these larvae include: chronic gastritis, ulcerated stomach, esophageal paralysis, peritonitis, stomach rupture, squamous cell tumors, and anemia (Pfizer 2007, Williams and Knapp 1999).

Medical Significance (Back to Top)

The horse bot fly occasionally can cause what is called ocular myiasis, or invasion of the eye by first stage larvae. Although these cases are rare, they often occur in individuals handling horses that have bot fly eggs on their hair. Occasionally, these bot fly larvae will enter the eye, rather than reside on the surface as is more common with the sheep nose bot, Oestrus ovis Linnaeus An additional rare form of horse bot myiasis is called cutaneous myiasis. In this case, hatching larvae enter the skin of humans and begin burrowing through the skin causing visible, sinuous, inflamed tracks accompanied by considerable irritation and itching (Catts and Mullen 2002). Anyone working with horses during bot fly season should be familiar with the risks and take appropriate precautions (do not rub eyes after combing or washing animals and wash hands when finished).

Figure 9. First stage larva of a horse bot fly, Gasterophilus sp., in a human eye. Photograph by Jerry Butler.

Management (Back to Top)

Mechanical control: Feces should be cleaned and transported away since this is the area where the final development occurs before the fly emerges. Bot eggs can be removed from the horse's body by several methods. A tool with a sharp edge or a form of sand paper can be used to scrape away the bot eggs. Warm water with appropriate insecticide can be used to induce the eggs to hatch and kill the larvae. The first stage larvae die soon after hatching if they do not reach the mouth. Protection, such as rubber gloves, help in preventing larvae from entering the handler.

Chemical control: An insecticide can also be applied weekly during the peak egg laying season to the areas of the body covered with bot eggs. Oral medications can be used to reduce the numbers of larvae inside of the stomach. Commonly used medications include avermectins, which come in different formulations: liquids, gels, boluses, and feed additives. Avermectins work to control the adult and larval fly stages (Peter et al. 2005). The horse should be treated within one month after eggs are seen during the early summer months. A second treatment should be administered in the Fall to control the second and third stage larvae.

Insect Management Guide for horse bots

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Catts EP, Mullen G. 2002. Myiasis (Muscoidea, Oestroidea). 318-347 pp. In Mullen G, Durden L. (editors). Medical and Veterinary Entomology. San Diego, CA. Academic Press.

- Cogley TP, Cogley MC. 2000. Field observations of the host-parasite relationship associated with the common horse bot fly, Gasterophilus intestinalis. Veterinary Parasitology 88: 93-105.

- Colwell DD, Otranto D, Horak IG. 2007. Comparative scanning electron microscopy of Gasterophilus third instars. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 21: 255-264.

- DuPonte MW, Larish LB. (2003). Horse bot fly, horse throat bot fly. College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources Publications. http://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/oc/freepubs/pdf/LM-10-3.pdf (20 September 2019).

- Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) (2007). Gasterophilus intestinalis De Geer. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=130298 (20 September 2019).

- Kaufman PE, Koehler PG, Butler JF. (2006). Horse bots. University of Florida EDIS. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IG136 (20 September 2019).

- North Dakota State University Agriculture and University Extension. (1991). Insect pests of horses (continued). Educational Materials. http://www.ag.ndsu.edu/pubs/ansci/horse/eb55-3.htm#horse (20 September 2019).

- Peter RJ, Van den Bossche P, Penzhorn BL, Sharp B. 2005. Tick, fly, and mosquito control — Lessons from the past, solutions for the future. Veterinary Parasitology 132: 205-215.

- Williams RE, Knapp FW. 1999. Flies and external parasites of horses. Horse Industry Handbook: 415.5-415.6.

- Zurek L. (2004). Horse bots: Gasterophilus intestinalis, horse bot fly; G. nasalis, throat bot fly; G. haemorrhoidalis, nose bot fly. Kansas State Research and Education. http://www.oznet.ksu.edu/entomology/medical_veterinary/GASTERO.html (no longer online).