common name: citrus whitefly

scientific name: Dialeurodes citri (Ashmead) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae)

Introduction - Distribution - Description - Identification - Life History and Habits - Hosts - Damage - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

The citrus whitefly, Dialeurodes citri (Ashmead), was once the most important citrus pest in Florida, but today it ranks below the snow scale, citrus rust mite, and several others. Nevertheless, it is still a serious pest in Florida. A native of India, it appears to have been introduced into Florida sometime between 1858 and 1885 (Morrill and Back 1911). It is now found throughout Florida and parts of other Gulf States and California and in greenhouses in many parts of the United States.

Figure 1. Adults of the citrus whitefly, Dialeurodes citri (Ashmead). Photograph by University of Florida.

Distribution (Back to Top)

Africa: Algeria

Asia: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, China (numerous provinces, including Hong Kong and Macau), India (numerous states), Israel, Japan, Lebanon, Pakistan, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam

Central America and Caribbean: Bahamas, Bermuda, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Puerto Rico

Commonwealth of Independent States: Azerbaijan, Russia, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan

Europe: Corsica, France, Georgia, Greece, Italy, Malta, Sardinia, Sicily, Spain, Turkey

North America: United States

South America: Argentina, Chile, Columbia, Guyana, Peru

[from IIE 1996)

In the United States, populations are established in Alabama, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia and Washington, D.C.

Some reported records of Dialeurodes citri apply to Dialeurodes citrifolii (Morgan), cloudywinged whitefly.

Description (Back to Top)

Adult: The adult is a tiny, mealy-white insect with four mealy-white wings that expand less than 1/8 of an inch (3.2 mm). The adults of both sexes have two pairs of wings covered with a white, powdery wax which gives the insects their common name. Cloudywinged whitefly adults have a darkened area in the middle of each wing, which is lacking in the wings of the citrus whitefly, and the wings fold to a flatter position than those of the citrus whitefly.

Nymph: The nymph is a flat, elliptical, scale-like object, closely fastened to the underside of a leaf. It becomes fixed after the first molt. The nymphs, after the first instar, are flattened, oval, and are similar in appearance to the early instars of the unarmored scale insects. Like the scale insects, whiteflies lose their normal legs and antennae after the first molt (they are kept, but are abbreviated), but unlike the scale insects, the females gain them back in the adult stage. The nymphs of the citrus whitefly lack a fringe of conspicuous, white, waxy plates or rods extending out from the margin of the body, which characterizes some species of whiteflies. Nymphs and pupae of the citrus and cloudywinged whiteflies are almost indistinguishable. Nymphs of both species are translucent, oval in outline, and very thin. Because the green color of the leaf shows through the body, nymphs are difficult to see. Pupae are similar but are thickened and are somewhat opaque, and eye spots of the developing adult may show through the pupal skin.

Figure 2. Eggs and nymphs of the citrus whitefly, Dialeurodes citri (Ashmead). Photograph by University of Florida.

Figure 3. Pupa of the citrus whitefly, Dialeurodes citri (Ashmead). Photograph by University of Florida.

Eggs: The citrus whitefly lays yellow eggs with a surface which is nearly smooth, distinguishing them from eggs of the cloudywinged whitefly which are yellow when freshly laid, but soon turn black and have a surface that is netted with a system of ridges.

Identification (Back to Top)

The identification key provided here is designed to identify the four major species of whiteflies that commonly infest citrus in Florida. Another key that covers 16 species of whiteflies that may infest Florida citrus was developed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services' Division of Plant Industry, and uses color photographs of nymphs to assist in identification. It is available here.

1a. The whitefly adult is white or white with dark spots on the wings. Nymphs are difficult to see or identify. . . . . 2

1b. The whitefly adult is slate blue in color, eggs are present and laid in spirals. Nymphs are black with prominent spines. . . . . citrus blackfly

2a. The whitefly adult is all white without any dark spots on wings. . . . . citrus whitefly

2b. The whitefly adult is white with a darkened area at the end of each wing. Occasionally a yellow

fungus is present. . . . . cloudywinged whitefly

2c. The whitefly female adult is all white and is surrounded by waxy filaments. Eggs are laid in a circle with the female at rest in the center. . . . . wooly whitefly

Life History and Habits (Back to Top)

The winter is passed in the mature larval or nymphal stage, usually on the undersides of leaves. Early in the spring pupae appear, and in March and April adults emerge. Eggs are deposited on foliage and hatch in eight to 24 days, depending on the season. Unfertilized eggs develop into males only. The nymphs soon settle to feed and do not move about until the adult stage is reached. There are several overlapping broods each year. Nymphal life span averages 23 to 30 days. Pupal development requires 13 to 30 days. The adult lives an average of about 10 days, but has been known to live for as long as 27 days. The adult female lays about 150 eggs under outdoor conditions. The entire life cycle from egg to adult requires from 41 to 333 days, but a great variation has been noted even among eggs laid on the same leaf on the same day.

Hosts (Back to Top)

Citrus is the most important host, but the following are also food plants — allamanda, banana shrub, Boston ivy, cape jasmine, chinaberry, crape myrtle, coffee, English ivy, Ficus macrophylla, gardenia, green ash, jasmine, laurel cherry, lilac, mock olive, myrtle, pear, privet, osage orange, persimmon, pomegranate, Portugal cherry, prickly ash, smilax, tree of heaven, trumpet vine, umbrella tree, water oak, and devilwood or wild olive.

Damage (Back to Top)

The whitefly injures the plant by consuming large quantities of sap, which it obtains with its sucking mouth parts. Further injury is caused by sooty mold fungus which grows over fruit and foliage in the copious amount of honeydew excreted by the whitefly. This black fungus may cover the leaves and fruit so completely that it interferes with the proper physiological activities of the trees. Heavily-infested trees become weak and produce small crops of insipid fruit. Also, fruit covered with sooty mold will be retarded in ripening and late in coloring, especially the upper part, which may remain green after the lower portion has assumed the color of ripe fruit. The fruit often must be washed before it is put on the market. A secondary injury to the trees may result from an excessive increase of the common scales of citrus which find protection under the sooty mold that covers leaves and branches.

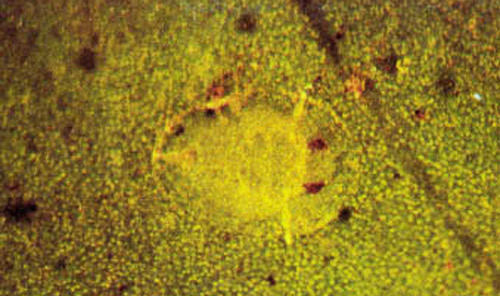

Figure 4. Citrus leaves with sooty mold growing on honeydew excreted by the citrus whitefly, Dialeurodes citri (Ashmead). Photograph by University of Florida.

Whiteflies become a problem when they continually sap the plant of energy needed for growth. This occurs when there is constant flushing and availability of new growth, such as after severe hedging and topping.

Management (Back to Top)

Biological control. Several parasites and predators attack the citrus whitefly. An introduced parasitoid wasp (Encarsia lahorensis Howard) is established in Florida's citrus regions and is reducing citrus whitefly populations. Delphastus pusillus (Lec.), a small dark brown ladybird beetle, feeds on the eggs but is never abundant. Delphastus catalinae (Horn), a California species, was introduced into Florida by University of Florida entomologists, and it also feeds on whitefly eggs. Cryptognatha flavescens Motsch., a coccinellid about 1/10 inch long and reddish brown, and another ladybird beetle, Verania cardoni Weise, were found by Woglum to feed on the citrus whitefly in India. Morrill and Back (1911) recorded two other ladybird beetles, Cycloneda sanguinea L. and Scymnus punctatus Melsh., that feed on the citrus whitefly in Florida, as well as a mirid bug, lacewings, mites, ants, and a species of thrips, Aleurodothrips fasciapennis Franklin.

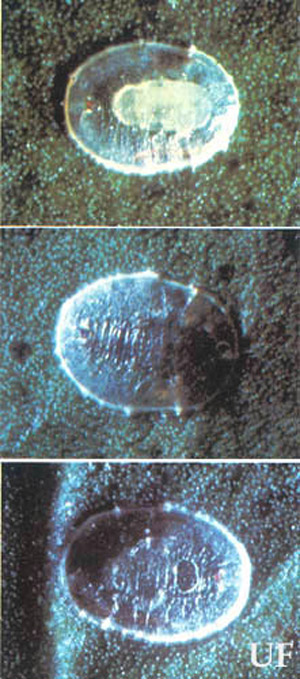

Figure 5. Citrus whitefly parasite, Encarsia lahorensis Howard, ovipositing in an immature citrus whitefly. Photograph by University of Florida.

Figure 6. Top: immature larva of the parasite, Encarsia lahorensis Howard, in a larva of a citrus whitefly, Dialeurodes citri (Ashmead); middle: Encarsia lahorensis pupa in citrus whitefly larva; bottom: emergence hole of an adult Encarsia lahorensis in a dead citrus whitefly larva. Photograph by University of Florida.

Figure 7. Adult coccinellid predator of whitefly nymphs, Delphastus catalinae. Photograph by Kim Hoelmer, USDA.

Figure 8. Lacewing larva (Chrysoperla sp.) feeding on whitefly nymphs. Photograph by Jack Dykinga, USD.

Parasitic fungi: In large commercial plantings of citrus, citrus whitefly and cloudywinged whitefly are largely controlled in rainy weather by whitefly fungi. Some important species are the red fungus (Aschersonia aleyrodis Webber) and the brown fungus (Aegerita webberi Fawcett). A yellow fungus, Aschersonia goldiana, does not attack the citrus whitefly, but is very effective against the cloudywinged whitefly. The presence of the yellow fungus guarantees that cloudywinged whitefly is present. These fungi are generally present in all citrus groves in Florida and increase in numbers when the proper environmental conditions prevail. These fungi are commonly referred to as "friendly fungi," and the two major species are often referred to as red Aschersonia and yellow Aschersonia.

Figure 9. Red, Aschersonia aleyrodis, and yellow, Aschersonia goldiana, Aschersonia fungi attacking immature whiteflies. Photograph by University of Florida.

Cultural control. A regularly maintained program of hedging and topping can help avoid whitefly problems.

Chemical control. Whiteflies also are controlled by sprays applied primarily for control of scale insects. Spraying of commercial citrus exclusively for whitefly control is seldom practiced in Florida. Recommended control measures for commercial or dooryard citrus are significantly different. Please consult the specific management guide for your situation.

It is important to note that spraying with copper for control of harmful fungal diseases will also inhibit growth of "friendly fungi" resulting in an increase in whitefly populations. Also, more than one application of sulfur per year can have an adverse effect on parasites. Spray oil has some insecticidal properties, but is primarily used to remove sooty mold which grows on the fruit and leaves.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Anonymous. 1960. Distribution maps of insect pests. June. Series A, Map No. 111. Commonwealth Institute of Entomology, London, England.

- Berger EW. 1909. White-fly studies in 1908. Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 97: 39-71.

- Byrne DN, Bellows TS. 1991. Whitefly biology. Annual Review of Entomology 36: 431-457.

- Campbell BC, Duffus JE, Baumann P. 1993. Determining whitefly species. Science 261: 1333.

- Cockerell TDA. 1903. White fly, (Aleyrodes citri) and its allies. Florida Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 67: 662-666.

- Davidson RH, Peairs LM. 1966. Insect Pests of Farm, Garden, and Orchard. John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York. 675 pp.

- Ebeling W. 1959. Subtropical Fruit Pests. Division of Agriculture Sciences, University of California, Berkeley. 436 pp.

- Gerling D. 1993.2. Approaches to the biological control of whiteflies. Florida Entomologist 75: 446-456.

- Hamon AB. (1997). Whitefly of citrus in Florida. FDACS. (no longer available online)

- Hardee DD. 1993. Resistance in aphids and whiteflies: principles and keys to management. Proceedings of the Beltwide Cotton Conference, Memphis, TN, p 20-23.

- Maskell WM. 1896. Contributions toward a monograph of the Aleurodidae, a family of Hemiptera-Homoptera. Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute 28 (n.s. vol. II) [1895]: 411-448.

- Metcalf RL, Metcalf RA. 1993. Destructive and Useful Insects, Their Habits and Control. McGraw-Hill Book Co., Inc., New York.

- Morgan HA. 1893. The orange and other citrus fruits, from seed to market, with insects beneficial and injurious, with remedies for the latter. Louisiana Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin 110: 1-36.

- Morrill AW, Back EA. 1911. White Flies Injurious to Citrus in Florida. USDA Bureau of Entomology Bulletin 92. 109 pp.

- Mound LA, Halsey SH. 1978. Whitefly of the World. A Systematic Catalogue of the Aleyrodidae (Homoptera) with Host Plant and Natural Enemy Data. British Museum (Natural History), London.

- Ponti OMB de, Romanow LR, Berlinger MJ. 1990. Whitefly-plant relationships: plant resistance. In Whiteflies: their Bionomics. Pest Status and Management. D. Gerling, (ed). Intercept Ltd, Andover UK. pp. 91-106.

- Pratt RM. 1958. Florida Guide to Citrus Insects, Diseases and Nutritional Disorders in Color. Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Florida, Gainesville. 191 pp.

- Quaintance AL. 1900. Contributions toward a monograph of the American Aleurodidae. USDA Division of Entomology Bulletin Technical Series 8: 1-64.

- Quaintance AL. 1907. The More Important Aleyrodidae Infesting Economic Plants, with Description of a New Species Infesting the Orange. USDA Bureau of Entomology Bulletin Technical Series 12, pt. 1. 93 pp.

- Quayle HJ. 1941. Insects of Citrus and Other Subtropical Fruits. Comstock Publ. Co., Inc., Ithaca, New York. 583 pp.

- Riley CV, Howard LO. 1893. The orange Aleyrodes. Insect Life 5: 219-226.

- Woglum RS. 1913. Report of a trip to India and the Orient in search of the natural enemies of the citrus white fly. USDA Bureau of Entomology Bulletin 120: 1-58.