common name: crabhole mosquito

scientific name: Deinocerites cancer Theobald (Insecta: Diptera: Culicidae)

Introduction - Distribution - Description and Identification - Life History - Importance as a Pest or Vector - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

All 18 species of the genus Deinocerites are crabhole specialists. Adult Deinocerites use the upper portions of land crab burrows as daytime resting sites and the immature stages of these mosquitoes develop in the water that accumulates at the bottom of these burrows. The distribution of Deinocerites is confined primarily to Central America, the West Indies and nearby parts of North and South America. Eight species are found only on the Atlantic basin, nine species are restricted to the Pacific coast, and only one species (Deinocerites pseudes) occurs on both coasts. Three species of Deinocerites are found in the United States: Deinocerites cancer in Florida, and Deinocerites mathesoni and Deinocerites pseudes in Texas. In addition to occupying an unusual microhabitat, Deinocerites exhibit several other unusual traits, which have been most thoroughly studied in the Florida crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer.

Distribution (Back to Top)

The geographic range of Deinocerites cancer includes Florida, the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles (excluding Puerto Rico) and coastal regions of Central America from the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico to the Bocas del Toro Province in Panama. Deinocerites cancer is commonly found in the upper elevations of mangrove swamps and grassy saltmarshes along Florida's east coast as far north as St. Johns County. This mosquito is relatively uncommon on Florida's west coast. Florida's crabhole mosquito is normally found in large or medium-sized burrows, such as those made by the great Atlantic land crab, Cardisoma guanhumi. The density of Cardisoma guanhumi burrows can exceed 1000 per acre in some coastal areas of southeastern Florida, but along the state's west coast these burrows are encountered only occasionally. The burrows constructed by these land crabs may extend for a meter or more before terminating just below the water table.

Figure 1. Distribution of the crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer Theobald. Illustration by James Newman, University of Florida.

Figure 2. Florida's crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer Theobald, is normally found in large or medium-sized burrows of the great Atlantic land crab. Photograph by David Mook, St. Lucie Mosquito Control Unit, Florida.

Figure 3. Great Atlantic land crab, Cardisoma guanhumi. Photograph by David Mook, St. Lucie Mosquito Control Unit, Florida.

Description and Identification (Back to Top)

Deinocerites cancer adults are medium-sized mosquitoes covered by dark or dull-colored scales. They look similar to mosquitoes of the genus Culex, but have much longer antennae. In both sexes, the maxillary palpi are short, the antennae are non-plumose and longer than the proboscis, and the scutum is covered with narrow brown scales and numerous long setae.

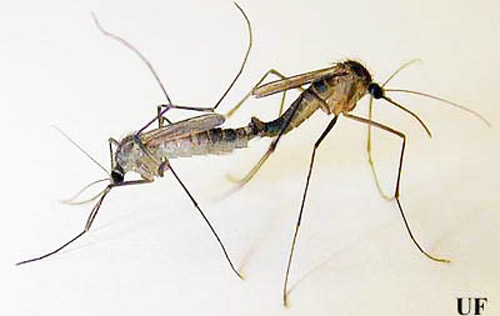

Figure 4. Male (right) and female (left) crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer Theobald. Photograph by James Newman, University of Florida.

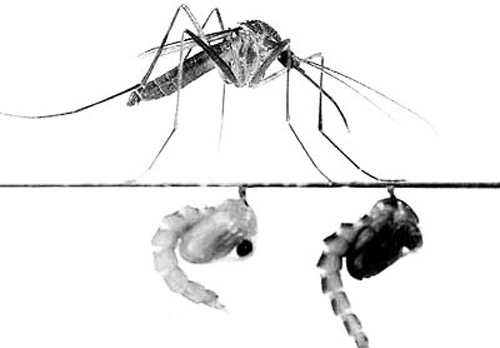

The fourth stage larva of Deinocerites cancer can be distinguished from those of other Florida mosquitoes by its round head which is widest near the bases of the antennae, an anal segment with dorsal and ventral sclerotized plates, and a single pair of short bulbous anal gills.

Figure 5. Fourth stage larvae of the crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer Theobald. Photograph by Michele Cutwa, University of Florida.

Life History (Back to Top)

Deinocerites cancer females lay their eggs singly on moist substrate just above the water surface in land crab burrows. Eggs hatch a few days after oviposition. Following eclosion, first stage larvae crawl down into the water where development proceeds through a total of four larval stages. Low temperatures, crowding, and suboptimal food levels extend the duration of the larval stages. Under favorable conditions, it usually takes the crabhole mosquito at least two to three weeks to complete larval development.

Waste products from land crabs probably enhance mosquito production by providing a food source for the larvae. By removing excessive debris and soil from their burrows land crabs also help to maintain an aquatic habitat for the crabhole mosquito. Without a resident land crab, old burrows rapidly become unsuitable for crabhole mosquitoes. Cardisoma guanhumi are herbivorous and normally remain in the burrows during the daylight hours, venturing out to feed only after sunset. This daily pattern of activity is interrupted when land crabs occasionally seal the entrance to their burrows with an earthen plug which may remain in place for several weeks or months. Crabhole mosquitoes may be trapped in these capped burrows.

Figure 6. Land crabs occasionally seal the entrances to their burrows with an earthen plug. Photograph by David Mook, St. Lucie Mosquito Control Unit, Florida.

Another inhabitant of land crab burrows is the killifish Rivulus marmoratus, which is particularly common in burrows that are more likely to be inundated by storm or seasonally high tides. Rivulus marmoratus can survive in the low oxygen and high hydrogen sulfide concentrations characteristic of the small, isolated aquatic habitats in land crab burrows, and it will readily devour Deinocerites cancer larvae. Other unusual traits enhancing the capacity of Rivulus marmoratus to prey on crabhole mosquito larvae include: the ability to move from one crabhole to another by scooting over damp soil, the capacity to lay eggs with delayed hatching under drought conditions, and the self-fertilizing hermaphroditic mode of reproduction which enables a single fish to colonize new habitats.

Figure 7. The killifish, Rivulus marmoratus, a predator of the crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer Theobald. Photograph by Michele Cutwa, University of Florida.

During the late summer and fall, estuarine water levels along Florida's southeast coast are typically much higher than they are during the rest of the year. These high water conditions invariably flood and submerge many land crab borrows near the estuarine intertidal zone, making the Deinocerites cancer larvae easy prey not only for Rivulus marmoratus but also for several other fish species. Nevertheless, land crabs adjust to these major floods by relocating further inland, and their new burrows are rapidly colonized by Deinocerites cancer.

The transformation from an aquatic to a terrestrial creature takes place in the non-feeding pupal stage. Deinocerites cancer pupae, like those of all mosquito species, are motile but tend to be inactive unless disturbed by other organisms. The pupal stage lasts just a few days.

Figure 8. Pupal stage of the crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer Theobald. Photograph by Michele Cutwa, University of Florida.

Newly emerged Deinocerites cancer females are sexually receptive to males, whereas the females of several other mosquito species will not mate for one or more days following emergence. Male Deinocerites cancer spend a considerable amount of time on the surface of the water where they exhibit a behavior called pupal attendance. The exceptionally long antennae of male Deinocerites have fewer sound collecting fimbrillae but more olfactory and mechanoreceptive sensilla than the males of other mosquito species. Using their highly specialized antennae, they search for female pupae. Once a pupa is located, the male attaches to the pupa's air trumpet with the tarsal claw of its foreleg, allowing the other legs to be used to fend off other males. Somehow male Deinocerites cancer can distinguish between male and female pupae, especially in the final hour before eclosion. An attending male will initiate the mating process even before an emerging female is free of her pupal case. Copulating pairs may remain together for 30 minutes or more. Pupal attendance is known to occur in only one other mosquito, Opifex fuscus.

Figure 9. The crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer Theobald, exhibiting pupal attendance. Photograph by Joe O'Neal.

Figure 10. Male crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer Theobald, attached to a pupa's air trumpet with the tarsal claw of its foreleg. Photograph by Joe O'Neal.

Deinocerites cancer females do not normally blood feed until after the first egg clutch, which is produced with carry-over reserves from the larval stage. Birds, particularly ciconiiforms, serve as the primary blood source, but feeding also occurs on various mammalian and reptilian species. There is no evidence that land crabs serve as a blood source for Deinocerites cancer. Both males and females obtain sugar meals from plant sources.

Importance as a Pest or Vector (Back to Top)

Deinocerites cancer populations seldom annoy humans with their blood feeding activity, and Florida's crabhole mosquito has not been implicated in the transmission of any human pathogen.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Adames AJ. 1971. Mosquito Studies (Diptera, Culicidae). XXIV. A revision of the crabhole mosquitoes of the genus Deinocerites. Contributions of the American Entomological Institute 7: 1-154.

- Conner WE, Itagaki H. 1984. Pupal attendance in the crabhole mosquito Deinocerites cancer: the effects of pupal sex and age. Physiological Entomology 9: 263-267.

- Cutwa MM, O'Meara GF. Identification guide to common mosquitoes of Florida. (no longer online).

- Edman JD. 1974. Host-feeding patterns of Florida mosquitoes. IV. Deinocerites. Journal of Medical Entomology 11: 105-107.

- O'Meara GF, Mook DH. 1990. Facultative blood-feeding in the crabhole mosquito, Deinocerites cancer. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 4: 117-123.

- O'Meara GF, Petersen JL. 1985. Effects of mating and sugar feeding on the expression of autogeny in crabhole mosquitoes of the genus Deinocerites (Diptera, Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 22: 485-490.

- Provost MW, Haeger JS. 1967. Mating and pupal attendance in Deinocerites cancer and comparisons with Opifex fuscus (Diptera: Culicidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 60: 565-574.

- Taylor DS. 1989. Room without a view. Natural History 9/89: 26-33

- Taylor DS. 1990. Adaptive specializations of the cyprinodont fish Rivulus marmoratus. Florida Science 53: 239-248.

- Wolcott TG, Wolcott DL. 1990. Wet behind the gills. Natural History 10/90: 46-55.