common name: cabbage webworm

scientific name: Hellula rogatalis (Hulst) (Insecta: Crambidae: Glaphyriinae)

Distribution - Synonymy - Description and Life Cycle - Host Plants - Damage - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

The cabbage webworm (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) is a pest of crucifers. It is found in the western hemisphere, but not in Hawaii (Solis 1986). For over 50 years, it was wrongly synonymized or identified as Hellula undalis (F.). Capps (1953) corrected the cabbage webworm species to Hellula rogatalis. However, Hellula undalis (F.) can be found in Hawaii and in warmer climates of Europe, Asia, and Africa (Capinera 2001). These two species can be distinguished by differences in adult male and female genitalia (Capps 1953).

Figure 1. Fifth instar cabbage webworm, Hellula rogatalis (Hulst). Photograph by Lyle Buss, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Synonymy (Back to Top)

G. D. Hulst first described this species as Botis rogatalis in 1886 (Hulst 1886).

Distribution (Back to Top)

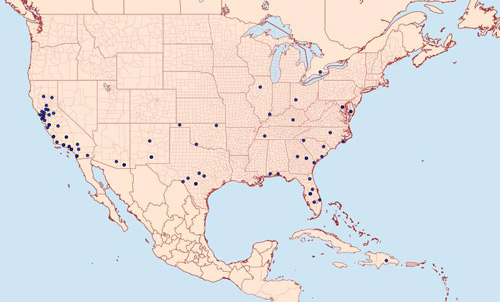

The cabbage webworm occurs throughout the southern United States and is a sporadic and destructive pest of crucifers in the southeastern United States (Figure 2) (Allyson 1981, Latheef and Irwin 1983, Vail et al. 1991). It has been reported as far north as Nova Scotia, Canada (Munroe 1972), but has rarely been reported to be a pest in northern latitudes.

Figure 2. Distribution map of Hellula rogatalis (Hulst). Figure from Moth Photographers Group at the Mississippi Entomological Museum at the Mississippi State University. (Accessed at http://mothphotographersgroup.msstate.edu/large_map.php?hodges=4846 on 10 November 2015). Used by permission.

Description and Life Cycle (Back to Top)

Eggs: Newly laid eggs (0.5-0.75 mm in diameter) are oval and slightly flattened, often being distinctly nipple-shaped at one end. Eggs are yellowish-green or gray with a reticulated surface; mature eggs turn pink. Eggs are laid singly or in small masses, usually on terminal leaves. The duration of the egg stage ranges from 2.02 days at 35°C to 23.89 days at 15°C. At 15°C, larvae were unsuccessful in pupating (McAvoy and Kok 1992).

Larvae: Early instar larvae are yellowish-gray without stripes; however, mature larvae are grayish-yellow, with five purple or black longitudinal stripes from head to tail (Figure 1). The thoracic legs are purplish-gray. Larvae have black, glossy heads, and the body is sparsely covered with setae (hairs), which are yellow or light brown and moderate in length (Munroe 1972, Allyson 1981). The width of the head capsules of each the larval instar from first to fifth is 0.19, 0.29, 0.49, 0.78, and 1.2 mm respectively, and body lengths are 0.91, 2.37, 4.78, 6.42, and 9.89 mm, respectively (McAvoy and Kok 1992). At 30°C, development times for each instar are 2.78, 2.36, 1.88, 2.37, and 4.39 days, respectively. The duration of all five instars ranges from 11.31 days at 35°C to 42.4 days at 20°C (McAvoy and Kok 1992).

Pupae: Larvae pupate after burrowing into the soil. Pupae are formed inside compact cocoons made of silk webbing and surrounding soil. (Chittenden and Marsh 1912). Pupae are 8.03 ± 0.43 (SEM) mm in length, with a thorax width of 2.29 ± 0.15 mm. The pupa is yellowish-brown. The duration of the pre-pupal stage ranges from 1.56 days at 35°C to 4.91 days at 35°C, and the pupal stage ranges from 4.96 days 35°C to 17.16 day at 20°C (McAvoy and Kok 1992).

Adults: The forewings of newly emerged males and females are light brown and gray, respectively, but become yellowish-brown after three to four days. The forewing has a dark kidney shaped spot and irregular whitish bands; the hind wing is grayish white with a darker margin (Figures 6 and 7). The wingspan ranges from 18 to 21 mm. In a laboratory study, the duration of the adult stage ranged from 4.92 days at 35°C to 25.46 days at 20°C (McAvoy and Kok 1992).

For all stages of development, there was an inverse relationship between temperature and time when reared at temperatures between 20 and 35°C. Total time for the life cycle ranged from 22.75 days at 35°C to 89.93 days at 20°C on broccoli (McAvoy and Kok 1992).

Figure 3. Adult female cabbage webworm, Hellula rogatalis (Hulst). Photograph by Lyle Buss, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Figure 4. Adult cabbage webworm, Hellula rogatalis (Hulst) (dorsal view). Photograph by Lyle Buss, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Host Plants (Back to Top)

Cabbage webworm feeds on many important cruciferous plants, including bok choy, broccoli, cabbage, Chinese cabbage, collard, kale, mustard, radish, rutabaga, shepherd’s purse, and turnip (Chittenden and Marsh 1912, Munroe 1972, Allyson 1981, Latheef and Irwin 1983, Kok and McAvoy 1989, Nuessly and Hentz 2002, Nuessly and Larsen 2013). Additional hosts are beet and purslane (Chittenden and Marsh 1912).

Damage (Back to Top)

First and second instar larvae feed between the upper and lower leaf epidermis, and the older larvae (third and fourth instar) feed on the lower surface of leaves. Larvae create webs and feed inside the protection of the webs. In addition, larvae feed on the midribs of leaves, which can cause the midribs to weaken and the leaves to break (Figure 3) (McAvoy and Kok 1992). In younger plants, larvae often bore into the main stem and stalk, causing the plants to wilt and die (Latheef and Irwin 1983).

Cabbage webworm can seriously damage crops when it attacks buds and growing tips, which can prevent head formation, making the crop unmarketable. In cabbage, two larvae per plant results in a high enough population to damage the bud, resulting in no head being formed (Nguyen and Workman 1979). Destruction of the main bud can cause the production of secondary buds (Figure 4), which are small and unable to mature by the time of harvest. Even if the main head sustains less damage, it can be severely disfigured (Figure 5). Larvae feeding on developing heads of broccoli can produce extensive webbing and deform the head (Kok and McAvoy 1989).

Cabbage webworm was reported to have completely destroyed approximately 500 cabbage plants (‘Copenhagen Market’) in a field trial in Virginia (Latheef and Irwin 1983). During a pesticide screening trial in Live Oak, Florida in 2015, Shrestha and Webb (unpublished) found many cabbage plants in untreated control plots destroyed by cabbage webworm.

Figure 5. Later instar of cabbage webworm, Hellula rogatalis (Hulst) feeding on midrib of cabbage leaf. Photograph by Deepak Shrestha, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Figure 6. Cabbage plant with secondary buds due to damage caused by cabbage webworm, Hellula rogatalis (Hulst). Blue arrows show secondary buds on cabbage plant. Photograph by Deepak Shrestha, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Figure 7. Cabbage plant damage and distorted growth caused by cabbage webworm, Hellula rogatalis (Hulst). Extensive webbing and frass can be seen in the lower part of the photo. Photograph by Deepak Shrestha, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida.

Management (Back to Top)

To control cabbage webworm effectively, insecticides should be applied when larvae are first seen and are small. Several insecticides used for other lepidopterous pests can be effective for controlling cabbage webworm. Various insecticides have been evaluated in Florida (Nuessly and Hentz 2002, Nuessly and Larsen 2013, Shrestha and Webb [unpublished]). No host plant resistance has been reported, but Vail et al. (1991) found more cabbage webworm larvae in late-maturing cultivars of broccoli than in early-maturing cultivars in Montgomery and Halifax counties, Virginia. In field surveys in Virginia and Florida, Latheef and Irwin (1983) and Nguyen and Workman (1979) observed no natural enemies of cabbage webworm, including parasitic wasps.

For specific insecticide recommendations see Florida Insect Management Guide for cole crops

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Allyson S. 1981. Description of the last instar larva of the cabbage webworm, Hellula rogatalis (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae), with a key to larvae of North American species of Hellula Guenée. The Canadian Entomologist 113: 361-364.

- Capinera JL. 2001. Family Pyralidae- borers, budworms, leaftiers, webworms and snout moths pp. 457-499. In Handbook of Vegetable Pests. Academic Press, California, USA.

- Capps HW. 1953. A correction in the synonymy of the cabbage webworm (Hellula undalis (F.) (Lepidoptera: Pyraustidae). Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Sciences 52. Part 1: 46- 47. (22 November 2015)

- Chittenden DH, Marsh HO. 1912. The imported cabbage webworm. USDA Bureau of Entomology Bulletin 109: 23-45.

- Hulst GD. 1886. Descriptions of new Pyralidae. pp. 145-168. In Transactions of the American Entomological Society and Proceedings of the Entomological Section of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Vol. XIII. Paul C. Stockhausen, Entomological Printer. Philadelphia. (22 November 2015)

- Kok L, McAvoy TJ. 1989. Fall broccoli pests and their parasites in Virginia. Journal of Entomological Science 24: 258-265.

- Latheef MA, Irwin RD. 1983. Seasonal abundance and parasitism of lepidopterous larvae on Brassica greens in Virginia. Journal of the Georgia Entomological Society 18: 164-168.

- McAvoy TJ, Kok LT. 1992. Development, oviposition, and feeding of the cabbage webworm (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Environmental Entomology 21: 527-533.

- Munroe E. 1972. The Moths of America North of Mexico, Fascicle 13-1B, Pyraloidea, Pyralidae comprising subfamilies Odontiinae and Glaphyriinae. pp. 198-199. E. W. Classey Limited and R. B. D. Publications Inc., London.

- Nuessly GS, Hentz M. 2002. Evaluation of insecticides for control of lepidopteran pests on Chinese cabbage, 2001. Arthropod Management Tests E17.

- Nuessly GS, Larsen NA. 2013. Evaluation of insecticides for control of insects on bok choy in Florida, 2012. Arthropod Management Tests E2.

- Nguyen, R, Workman RB. 1979. Seasonal abundance and parasites of the imported cabbageworm, diamondback moth, and cabbage webworm in northeast Florida. Florida Entomologist 62: 68-69.

- Solis MA. 1986. Key to selected Pyraloidea (Lepidoptera) larvae intercepted at U. S. ports of entry: Revision of Pyraloidea in Keys to some frequently intercepted lepidopterous larvae by Weisman 1986 (updated 2006). USDA Systematic Entomology Laboratory. Paper 1. (22 November 2015).

- Vail KM, Kok LT, McAvoy TJ. 1991. Cultivar preferences of lepidopterous pests of broccoli. Crop Protection 10: 199-204.