common name: black and yellow mud dauber

scientific name: Sceliphron caementarium (Drury, 1773) (Insecta: Hymenoptera: Sphecidae)

Introduction - Distribution - Identification - Biology - Life History - Hosts - Importance - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

The black and yellow mud dauber, Sceliphron caementarium (Drury), is a common and widely distributed solitary sphecid wasp that hunts spiders and builds characteristic mud nests for their offspring (Figure 1). In each cell of her nest, a female mud dauber lays a single egg which she provisions with up to twenty-five live, paralyzed spiders. Mud dauber nests may be considered a nuisance because they are often built on urban structures. However, stings are rare and not of medical importance to humans.

Figure 1. A female Sceliphron caementarium (Drury), on her mud nest. Photograph by Erin C. Powell, University of Florida.

Synonymy (Back to Top)

The following synonyms are listed by ITIS (2015).

Pelopaeus solieri Lepeletier de Saint Fargeau, 1845

Pelopeus tahitensis de Saussure, 1867

Pelopoeus architectus Lepeletier de Saint Fargeau, 1845

Pelopoeus canadensis F. Smith, 1856

Pelopoeus nigriventris A. Costa, 1864

Pelopoeus servillei Lepeletier de Saint Fargeau, 1845

Sceliphron affine Fabricius, 1793

Sphex affinis Fabricius, 1793

Sphex caementarius Drury, 1773

Sphex economicus Curtiss, 1938

Sphex flavipes Fabricius, 1781

Sphex flavipunctatus Christ, 1791

Sphex flavomaculatus De Geer, 1773

Sphex lunatus Fabricius, 1775

Distribution (Back to Top)

Sceliphron caementarium is native to North America and has been reported in Central and South America, Asia, Europe, Australia, and on islands such as New Zealand, Hawaii, Fiji, Samoa, and Madeira (Krombein et al.1979, Harris 1997). In North America, they can be found throughout the United States, in southern Canada, and in Mexico (Evans 2007).

Identification (Back to Top)

Sceliphron caementarium is a black wasp with yellow markings and a very thin, long pedicel (the structure that connects the thorax and abdomen) (Figure 1). The yellow markings vary among individuals but are likely to be found on the base of the antenna (the scape), the dorsal side of the thorax, the base of the abdomen where it meets the pedicel, and the legs (Figure 2). Females are larger than males, measuring 23 to 25 mm in length, while males are approximately 21 mm in length (Evans 2011, Kim et al. 2014). Nests of Sceliphron caementarium can be recognized by their clustered, rectangular structure (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Female Sceliphron caementarium (Drury). Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Figure 3. A Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) nest depicting exit holes where adults have exited after completing the immature stages. This nest is made up of around 25 cells. Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Sceliphron caementarium can be easily distinguished from other North American mud dauber wasps. Sceliphron assimile (Dahlbom) is the only other Sceliphron species native to the United States (Krombein et al. 1979). This species ranges from Texas to Mexico and is characterized by its black hind legs, whereas Sceliphron caementarium has yellow markings on the hind legs (Krombein et al. 1979). The mud nest of Sceliphron assimile (Dahlbom) is similar to that of Sceliphron caementarium with rectangular nests made up of multiple cells (Bohart and Menke 1976).

The Asiatic mud dauber, Sceliphron curvatum (Smith), has been periodically observed in the United States since 2017 (with cases documented on websites such as iNaturalist), but it is not yet known whether this species is established or what its exact distribution might be. This species can be distinguished from S. caementarium by the reddish brown coloration, the striped pattern on the abdomen, as well as differences in nest shape. Sceliphron curvatum makes nests with each individual cell separate from the rest (Schmid-Egger 2005).

Two other genera of spider-hunting, mud dauber wasps found in the United States are Chalybion and Trypoxylon. The blue metallic mud dauber (Chalybion californicum) (Saussure) (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) is distributed throughout the U.S., has distinctive metallic blue body coloration, and can be seen renovating and reusing the mud nests of Sceliphron caementarium (Krombein et al. 1979, Figure 4). These nests have a patchy appearance where the blue metallic mud dauber has sealed over old Sceliphron exit holes (H. J. Brockmann, pers. comm. 2015). The organ pipe mud dauber (Trypoxylon politum) (Say) (Hymenoptera: Crabronidae) has black body coloration and builds distinctive tubular mud nests (Evans 2007) (Figure 5). The organ pipe mud dauber is thicker bodied, has white tarsi on the hind legs, and has a more robust, club shaped pedicel compared to Chalybion californicum (Figure 6).

Figure 4. A blue metallic mud dauber (Chalybion californicum) (Saussure) on a Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) nest. Photograph by J. L. Castner, University of Florida.

Figure 5. A nest of an organ pipe mud dauber, Trypoxylon politum (Say). Photograph by Lyle Buss, University of Florida.

Figure 6. A male organ pipe mud dauber, Trypoxylon politum (Say). Photograph by Lyle Buss, University of Florida.

Biology (Back to Top)

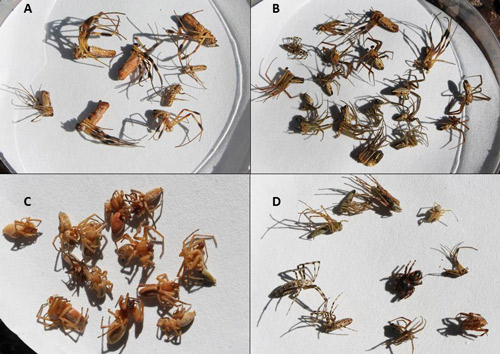

Sceliphron caementarium females capture and paralyze spider prey to provision their offspring. Females prefer spider taxa that build two-dimensional orb webs (e.g. family Araneidae) over taxa that build three-dimensional cob webs (e.g., family Theridiidae) (Blackledge 2003). Females will capture spider prey belonging to various spider taxa, e.g., golden silk orb weavers (Nephilidae), orb weavers (Araneidae), long-jawed orb weavers (Tetragnathidae), lynx spiders (Oxyopidae), crab spiders (Thomisidae), jumping spiders (Salticidae), and sac spiders (Anyphaenidae), but have a preference for web builders (Muma and Jeffers 1946, Crawford 1986, Uma and Weiss 2010, Powell and Taylor 2017, Figures 7, 9, 10, 11). Females display individual foraging specialization, where different females in the population specialize on different prey types despite access to common resources (Dean et al. 1988, Volkova et al. 1999, Powell and Taylor 2017, Figure 9, 10, 11). Furthermore, some females are highly specialized and only capture a single species of spider, while others are generalists that capture spiders ranging across many families (Powell and Taylor 2017). Female wasps occasionally steal spider prey from other female wasps’ nests, a behavior known as kleptoparasitism (Powell and Taylor 2017).

Spiders are captured and stung near the subesophageal ganglion, which induces paralysis that is unrecoverable (Coville 1987, Shafer 1949). Paralysis reduces the ability of the spider to injure the adult wasp or immature wasp while preserving the body until the larva is ready to feed on it (Shafer 1949). An egg is typically laid on the first spider, which is placed in the back of the cell, though it may be laid on the second or third spider in the cell (Shafer 1949). The female will continue to hunt, paralyze, and pack spiders into the cell until it is full, which may be up to 25 spiders (Obin 1982, Figures 7, 8, 9, 10, 11). She will then gather more mud to cap the cell and begin building the next cell (Shafer 1949). When the wasp egg hatches, the larva will eat the provided spiders, beginning with the hemolymph and eventually consuming the entire spider including the exoskeleton and legs (Shafer 1949). The larva will pupate after all the spiders within a cell are consumed; in a laboratory setting, they will eat additional spiders if provided (Shafer 1949, Joshi 1989).

After females have mated, they gather balls of mud in their mandibles (Figure 8) and fly to the selected nest site. Once a single cell is completed, they begin to hunt for spiders to provision that cell (Shafer 1949). Mud dauber wasps have good vision and are able to use landmarks to locate their nests (Ferguson and Hunt 1988). Female Sceliphron caementarium often build their nests on urban structures such as the eaves of homes, buildings, and bridges (Evans 2007). Nest site suitability depends on shelter from the elements, mud availability, and spider prey availability (Coville 1987, Shafer 1949). Males are not involved in nest building or guarding, but aggregate around flowers, feeding on nectar while waiting to mate (Shafer 1949). Adults are diurnal and most active in the late spring and summer in temperate regions, though in the tropics they are active throughout the entire year (Coville 1987). Adult Sceliphron caementarium feed on nectar and the hemolymph of their spider prey (Coville 1987).

Figure 7. Female Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) with a paralyzed spider in her mandibles. She is preparing to push it inside the mud nest. Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Figure 8. Female Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) gathering a mud ball to construct her nest. Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Figure 9. Paralyzed spider prey (Family: Araneidae) packed into a cell of Sceliphron caementarium (Drury). Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Figure 10. Spider prey from the nests of four different individual female Sceliphron caementarium (Drury). Each photo (a-d) depicts the prey from a different female wasp highlighting the fact that individuals specialize on different types of spider prey. a. spiders in the family Araneidae (Trichonephila clavipes), b. Araneidae, c. Anyphaenidae, d. Araneidae, Oxyopidae, Eutichuridae, and Salticidae. Photographs by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Figure 11. Cell contents of a Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) nest. Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Life Cycle (Back to Top)

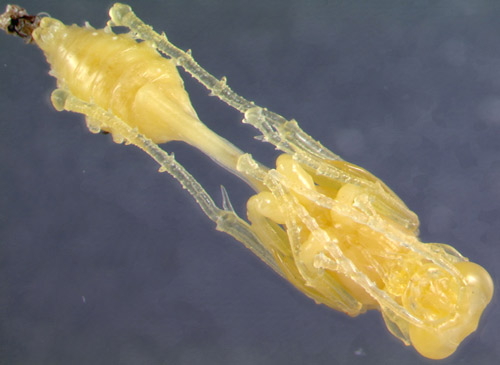

The female deposits a single egg onto the abdomen of one of the first spiders she places in a cell (Shafer 1949). The egg is cream or white in color and curved in shape, measuring between 0.3 and 0.4 millimeters (Shafer 1949). The larva ecloses (hatches) from the egg after one and a half to three and a half days (Coville 1987, Shafer 1949). The color of the larva begins as cream and becomes brighter yellow as it grows (Figures 10, 11). The larva consumes all of the provisioned spider prey within one to three weeks, depending on temperature (Figure 12) (Coville 1987, Shafer 1949). The pre-pupal stage will go into diapause in the winter until the temperature increases (Coville 1987, Shafer 1949). The pupal case, or cocoon, is spun within the nest cell and is reddish brown, thin, and oblong-shaped (see Figure 10, 11, 12) (Shafer 1949). The adult will live for three to six weeks after emergence (Coville 1987). Sceliphron caementarium is multivoltine (multiple generations per year) (Shafer 1949).

Figure 12. From left to right: The pupal case, pupa, pre-pupal larva, and last instar of Sceliphron caementarium (Drury). Photograph by Lyle Buss (ljbuss@ufl.edu), University of Florida.

Figure 13. From top to bottom: A pupa within a pupal case, a larva that has begun to spin the pupal case, and a last instar larva of Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) that has consumed all the spider prey. Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Figure 14. Young pupa of Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) with cast larval skin at the tip of the abdomen. Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Natural Enemies (Back to Top)

There are numerous parasites and parasitoids of Sceliphron caementarium and their nests. Many wasps and flies parasitize immature stages of Sceliphron caementarium by killing and consuming the immature mud dauber. Parasites may also consume the spider prey in the nest. The parasitoid wasp Melittobia (Eulophidae) is perhaps the most significant natural enemy of Sceliphron caementarium (Matthews et al. 2009). Bee flies (Bombyliidae), flesh flies (Sarcophagidae), cuckoo wasps (Chrysididae), and velvet ants (Mutillidae) are also reported to use Sceliphron caementarium as a host in Florida (Obin 1982). An Italian study reported 24 different parasites or parasitoids that emerged from Sceliphron caementarium nests (Campadelli 1998).

In addition to parasites and parasitoids, several predators may eat mud daubers. Sceliphron caementarium are sometimes captured by the spiders that they are hunting, or by spiders that live nearby their nest sites (E. Powell pers. obs., Figure 15). They are also hunted by birds, which may catch adult wasps in flight or even systematically remove larvae or pupae from the nests (Smith 1986; Coward and Matthews 1995).

Figure 15. A female southern house spider (Kukulcania hibernalis) with Sceliphron caementarium prey. Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Pest Status (Back to Top)

While mud daubers tend to live in sites heavy with human activity, Sceliphron caementarium is docile and rarely stings (Shafer 1949, Figure 16). While nests are often dense in certain areas, individual wasps build solitary nests that they do not defend and will only sting a human when handled roughly. This species is considered an aesthetic pest due to the unsightly appearance of mud nests, which may become very dense, on buildings (Figure 17). Females who choose unique locations to build nests may cause serious problems for airplanes, car engines (Figure 18), and other mechanical devices, with nests speculated to have caused fatal plane crashes (Cloe 1980).

Figure 16. Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) is a docile species that rarely stings. Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Figure 17. The underside of a bridge in north-central Florida with a high density of Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) mud nests. Photograph by Erin Powell, University of Florida.

Figure 18. Nests of Sceliphron caementarium (Drury) built on various household items in Florida. Photographs by Erin Powell and A. Powell, University of Florida.

Venom (Back to Top)

The composition of Sceliphron caementarium venom differs greatly from the venom of other social wasps and bees. They have a significantly smaller amount of venom; common wasps, such as Vespa spp., may have 10 times venom within the venom apparatus (O’Connor and Rosenbrook 1963). Sceliphron caementarium venom lacks the antigenic properties, histamines, serotonin, acetylcholine, and small peptides such as pain-producing kinin, that other hymenopteran venom contains (Rosenbrook and O’Connor 1964). Additionally, Sceliphron caementarium lacks Dufour’s alkaline gland found in social wasps (Rosenbrook and O’Connor 1964). These properties may explain why the venom is mild with negligible pain or swelling (O’Connor and Rosenbrook 1963). While most wasps and bees use venom for defense, Sceliphron caementarium uses venom to paralyze spiders which does not require the above compounds (Rosenbrook and O’Connor 1964).

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Blackledge TA, Coddington JA, Gillespie RG. 2003. Are three-dimensional spider webs defensive adaptations? Ecology Letters 6: 13-18.

- Bohart RM, Menke AS. 1976. Sphecid wasps of the world: A generic revision. Berkeley: University of California Press. 694 pp.

- Campadelli G, Paglian G, Scaramozzino PL, Strumia F. 1998. Parasitoids of Sceliphron caemenatrium (Drury) (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) and other insects utilizing its nests in Romagna. Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali Bollettino (Turin) 16: 225-240.

- Cloe C. 1980. Flight to Freeport crashes; 34 dead. In The Palm Beach Post, pp. 372. West Palm Beach, FL.

- Coville RE. 1987. Spider-hunting sphecid wasps. In Nentwig W. (ed). Ecophysiology of Spiders. Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag. 309-319.

- Coward, SJ, Matthews RW. 1995. Tufted titmouse (Parus bicolor) Predation on mud-dauber wasp prepupae (Trypoxylon politum). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 68: 371-373.

- Crawford RL. 1986. Spider prey of the mud-dauber, Sceliphron caementarium (Sphecidae) in Washington. Washington State Entomological Society Proceedings: 797-800.

- Dean DA, Nyffeler M, Sterling WL. 1988. Natural enemies of spiders—mud dauber wasps in east Texas (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae). Southwestern Entomologist 13: 283-290.

- Evans AV, National Wildlife Federation. 2007. National Wildlife Federation field guide to insects and spiders and related species of North America. New York: Sterling Pub. 494 pp.

- Ferguson CS, Hunt JH. 1989. Near-nest behavior of a solitary mud-daubing wasp, Sceliphron caementarium (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae). Journal of Insect Behavior 2: 315-23.

- Harris AC. 1997. A nest and life-history stages of Sceliphron caementarium (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) intercepted in Fiordland. Weta 20: 6-8.

- Joshi PV. 1989. Studies on the feeding behaviour of the larvae of Sceliphron violaceum (Sphecidae, Hymenoptera). Biovigyanam 15: 109-10.

- Kim DW, Yeo JD, Kim JK. 2014. Revision of the family Sphecidae (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) in South Korea. Entomological Research 44: 271-92.

- Krombein KV, Hurd Jr PD, Smith DR, Burkes BD. 1979. Catalog of Hymenoptera in America north of Mexico. Vol. II. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. 2735 pp.

- Matthews RW, Gonzalez JM, Matthews JR, Deyrup LD. 2009. Biology of the parasitoid Melittobia (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae). Annual Review of Entomology 54: 251-66.

- Muma MH, Jeffers WF. 1945. Studies of the spider prey of several mud-dauber wasps. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 38: 245-55.

- Obin MS. 1982. Spiders living at wasp nesting sites: What constrains predation by mud-daubers? Psyche (Cambridge) 89: 321-35.

- O’Connor Jr R, Rosenbrook W. 1963. Venom of mud-dauber wasps. 1. Sceliphron Caementarium - preliminary separations and free amino acid content. Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Physiology 41: 1943-48.

- Powell EC, Taylor LA. 2017. Specialists and generalists coexist within a population of spider-hunting mud dauber wasps. Behavioral Ecology 28: 890-898.

- Rosenbrook, W, O’Connor Jr R. 1964. Venom of mud-dauber wasps. 2. Sceliphron caementarium - protein content. Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Physiology 42: 1005-10.

- Schmid-Egger C. 2005. Sceliphron curvatum (F. Smith 1870) in Europa mit einem Bestimmungsschlüssel für die europäischen und mediterranen Sceliphron-Arten (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae). Bembix, 19: 7-28.

- Shafer GD. 1949. The ways of a mud dauber. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 78 pp.

- Smith KG. 1986. Downy woodpecker feeding on mud-dauber wasp nests. The Southwestern Naturalist, 31: 134-134.

- Uma DB, Weiss MR. 2010. Chemical mediation of prey recognition by spider-hunting wasps. Ethology 116: 85-95.

- Volkova T, Matthews RW, Barber MC. 1999. Spider prey of two mud dauber wasps (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae) nesting in Georgia's Okefenokee Swamp. Journal of Entomological Science 34: 322-27.