common name: olive bud mite, olive leaf and flower mite (suggested common names)

scientific name: Oxycenus maxwelli (Keifer, 1939) (Arachnida: Acari: Eriophyidae)

Introduction - Distribution - Description - Life Cycle - Hosts - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

The olive bud mite, Oxycenus maxwelli (Keifer), was first found by Dr. K. E. Maxwell in Santa Paula, California (Keifer 1939). Dr. Maxwell, for whom the species is named, sent these mites to Hartford H. Keifer for identification and Keifer classified the mites as a new species, which he named Oxypleurites maxwelli, in the family Eriophyidae, within the superfamily Eriophyoidea. The Eriophyidae consist of 274 genera and about 3,790 species (Vacante 2016). The superfamily Eriophyoidea contains the smallest plant-feeding arthropods, averaging 100 to 500 microns (0.1 to 0.5 mm) in length (Hoy 2011). Eriophyids parasitize plants, but rarely cause enough damage to cause plant mortality. Eriophyoids can be split into groups based on the damage they cause: gall, bud, rust, or blister (Graham and Johnson 2004). Oxycenus maxwelli (Figure 1), as the common name reveals, falls into the bud mite category because they lay their eggs near buds and feed on bud tissue.

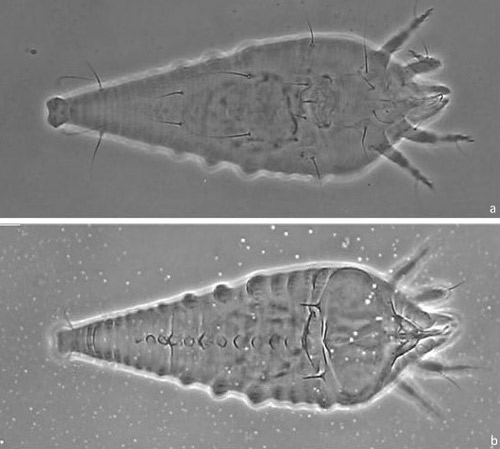

Figure 1. Micrograph of female Oxycenus maxwelli (Keifer) showing a ventral view (a) and a dorsal view (b). Photograph by Paulo R. Reis, EPAMIG Sul de Minas/EcoCentro, Brazil.

Distribution (Back to Top)

The olive bud mite is the sole eriophyid reported on olive trees in the United States (Lindquist et al. 1996). Presently the mite has been found in California (Vacante 2016) and Florida (Florida State Record E2014-7171-1, submitted by Gillett-Kaufman 2015). These mites have affected olives in many countries in the Mediterranean area, including Algeria, Egypt, Greece, Italy, Malta, Montenegro, and Spain. Other reports of this mite have come from Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Chile, Iran, Portugal, and South Africa (Lindquist et al. 1996, Vacante 2016). The olive bud mite has a worldwide distribution because it follows the spread of olive trees (Vacante 2016).

Description (Back to Top)

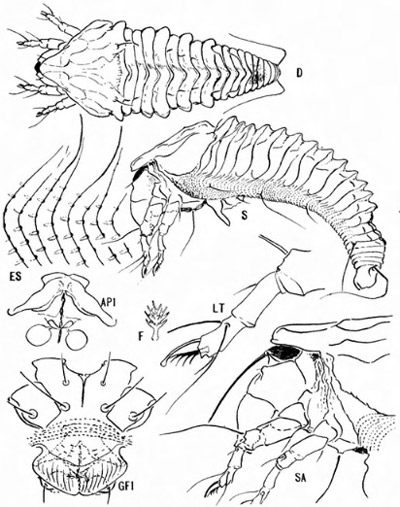

Mites have two body segments: the head region is referred to as the gnathosoma and the rest of the body is referred to as the idiosoma (Jeppson et al. 1975). The bodies and legs of mites have setae (small hair-like structures used as sensory organs), but the olive bud mite bears very few (Lindquist et al. 1996). Typically mites have three pairs of legs during their larval stage and four pairs of legs during their nymphal and adult stages. Eriophyid mites hatch with two pairs of legs located near the anterior end the body (toward the head) and do not develop additional legs (DMNC 2016). Eriophyoid mites lack eyes, though they have a pair of primitive eye-like projections that may be receptive to light (Lindquist et al. 1996). Eriophyoids have a well-developed empodium—a spine-like projection located between the two claws on the final leg segment—on each foreleg, which is termed a “featherclaw” due to its branched rays (Lindquist et al. 1996). The olive bud mite’s most characteristic traits are a serrated back, a notched posterior abdominal segment (as opposed to flattened), and unevenly projecting tergites (dorsal body segments) (Figure 2) (Keifer 1939). Identification of these mites must be done by a specialist using a high power microscope to properly distinguish from the 11 other species of olive mites.

Figure 2. Illustration of Oxycenus maxwelli (Keifer) showing a dorsal view (D), side view (S), detail of side skin (ES), anterior apodeme and associated internal genital structures (AP1), featherclaw (F), tarsus and adjacent points (LT), female genitalia and coxae (GF1), and side view of anterior part (SA). Graphic by H.H. Keifer, California State Department of Agriculture.

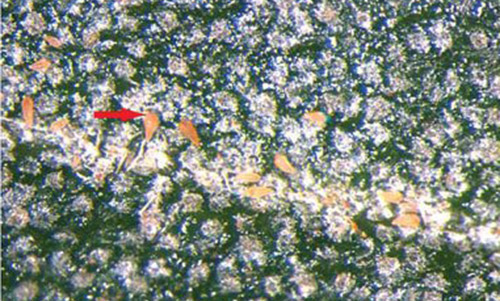

Because these mites are microscopic, they are generally identified by host plant and visible damage (Graham and Johnson 2004). When an olive bud mite infestation occurs, olive flowers fall prematurely, buds experience discoloration and drop, and leaves become spotted and distorted in shape resulting in longitudinal curling (Figure 3) (Vacante 2016, Jeppson et al. 1975). If the olive leaves curl, there is reduced light absorption and photosynthesis decreases (Reis et al. 2011). Just two to three mites per leaf can affect the leaf shape (Vacante 2016). Young plants suffering from bud infestations, which are especially prevalent during the spring and fall, can experience growth inhibition (Knihinicki 2010).

Figure 3. Curling of olive (Olea europaea L.) leaves caused by Oxycenus maxwelli (Keifer). Photograph by Paulo R. Reis, EPAMIG Sul de Minas/EcoCentro, Brazil.

Life Cycle (Back to Top)

Eggs: Female olive bud mites deposit about 50 eggs in their lifetime (Hoy 2011). The eggs are laid on leaves or near buds. A male mite leaves a spermatophore (package of sperm) on leaves of the host plant, which are taken up into the female’s spermatheca. Males do not need to be present for females to pick up the spermatophores and females do not need to be present for males to leave spermatophores, which is called sex dissociation (Vacante 2016). Because eriophyids display arrhenotokous parthenogenesis, fertilized eggs develop into females, but if a female runs out of sperm or cannot find a spermatophore, unfertilized eggs will develop into males (DMNC 2016).

Larvae and Nymphs: The larvae that emerge from the eggs have two pairs of legs and lack true genitalia. As the larvae grow, they eventually reach the nymphal stage. The nymphs and larvae are distinguishable only by their size (Lindquist et al. 1996). Inactive periods—in which the young mites do not feed—characterize stages of the eriophyid life cycle between the larval and nymphal stage and also between the nymphal and adult stage that are called the nymphochrysalis and imagochrysalis, respectively (Vacante 2016).

Adults: Adult olive bud mite males range from 125 to 145 microns long (0.13 to 0.15 mm) and adult females range from 140 to 160 microns long (0.14 to 0.16 mm) (Jeppson et al. 1975). The olive bud mite has a wedge-shaped, flattened body that is yellow to orange in color (Figure 4) (Vacante 2016).

Figure 4. Multiple olive bud mites, Oxycenus maxwelli (Keifer), on the upper surface of an olive, Olea europaea L., leaf. Photograph by Paulo R. Reis, EPAMIG Sul de Minas/EcoCentro, Brazil.

In the spring, the olive bud mites move to new leaves and buds to reproduce (Knihinicki 2010). These mites will congregate on flower stalks, and can cause flowers to drop prematurely if there is extensive feeding damage (Jeppson et al. 1975). As many as 100 mites can be found per flower when population densities are high (Knihinicki 2010). Individuals will move to young fruits, which can cause the fruits to become gray and shrivel around punctures made by the mites feeding (Vacante 2016). Olive bud mites will return to the leaves in summer where populations usually decrease (Knihinicki 2010).

Hosts (Back to Top)

Most eriophyids are host specific (Graham and Johnson 2004). The only known host of Oxycenus maxwelli is the olive tree, Olea europaea L. (Figure 5), and this mite is one of 12 recorded species belonging to the superfamily Eriophyoidea that can be found feeding on the plant (Reis et al. 2011). The olive bud mite tends to feed on the upper surface of olive leaves, though some individuals will feed on the underside of leaves when the population is high; the mites prefer new buds and leaves (Keifer 1939, Knihinicki 2010). The University of California has found that the Ascolano olive variety is the most susceptible in California, followed by the Sevillano, Manzanillo, and Mission (Knihinicki 2010).

Figure 5. An olive bud mite, Oxycenus maxwelli (Keifer), susceptible mission olive tree (Olea europaea L.) in Marion County, Florida. Photograph by Jennifer L. Gillett-Kaufman, University of Florida.

Management (Back to Top)

Oxycenus maxwelli does not usually cause extensive damage to its olive tree host, and even large populations can be tolerated (Graham and Johnson 2004) (this is common with eriophyids; if outbreaks occur it is usually because natural enemies are disrupted). If an extremely high population density occurs in early spring, control treatments are suggested. Hundreds of mites per inflorescence (flower head) can cause substantial yield loss (Vacante 2016). For quick detection and removal of the olive bud mite, foliage should be examined for color changes or leaf shape distortion (Figure 3) early in the season (Graham and Johnson 2004).

According to the University of California Pest Management Guidelines, management is only required if crop yields have been below normal for several consecutive years. When this happens, the olive tree shoot tips and developing buds are examined in spring for olive bud mite presence (Vacante 2016). If large populations exist, the olive trees receive treatment before the buds bloom.

Though chemicals should be avoided to preserve natural enemies, sulfur products have been used in the past (Lindquist et al. 1996). Wettable sulfur has proven effective when applied before olive flowers bloom, but damage to the tree can occur at temperatures above 32.2°C. For high temperatures, dusting sulfur is safer to use than wettable sulfur. Spraying sulfur is another option (Vacante 2016). Horticultural summer oils should be considered and may be less disruptive to natural enemies because they have a shorter residual time than sulfur products. Oils should be applied to well-watered olive trees when the temperatures are cooler.

Natural enemies of the olive bud mite have been reported but are not known in the United States. In Australia, some phytoseiid mites, like Euseius elinae (Schicha), prey on the olive bud mite. Also, lady beetles (Stethorus spp.) act as a biological control. In Argentina, a stigmaeid mite, Agistemus aimogastaensis, was discovered as a predator of the olive bud mite (Leiva et al. 2013).

Selected References (Back to Top)

- DMNC. (2016). What are eriophyid mites? The Digital Museum of Nature and Culture. National Digital Archives Program. (7 January 2016)

- Graham J, Johnson WS. 2004. Ornamental plant damage by eriophyid mites (and what to do about it).University of Nevada, Reno Cooperative Extension. Fact sheet 04-47. (12 January 2016)

- Hoy, MA. 2011. Agricultural acarology: Introduction to integrated mite management. CRC Press, Boca Raton, USA.

- Jeppson LR, Keifer HH, Baker EW. 1975. Mites injurious to economic plants. University of California Press, Berkeley, USA.

- Keifer HH. 1939. Eriophyid studies III. California State Department of Agriculture, State of California Bulletin 28: 144-162.

- Knihinicki D. 2010. Olive bud mite – Oxycenus maxwelli. Industry and Investment New South Wales Government. Fact sheet 1048. (8 January 2016)

- Leiva S, Fernandez N, Theron P, Rollard C. 2013. Agistemus aimogastaensis sp. n. (Acari, Actinedida, Stigmaeidae), a recently discovered predator of eriophyid mites Aceria oleae and Oxycenus maxwelli, in olive orchards in Argentina. ZooKeys 312: 65-78.

- Lindquist EE, Sabelis MW, Bruin J. 1996. Eriophyid mites: Their biology, natural enemies and control, vol. 6. Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

- Reis PR, de Oliveira AF, Navia D. 2011. First record of the olive bud mite Oxycenus maxwelli (Keifer) (Acari: Eriophyidae) from Brazil. Neotropical Entomology 40: 622-624.

- Vacante V. 2016. The handbook of mites of economic plants: Identification, bio-ecology and control. Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International (CABI), Oxfordshire, UK.