common name: Asian citrus psyllid

scientific name: Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Insecta: Hemiptera: Psyllidae)

Introduction - Distribution - Description and Identification - Life History - Damage - Host Plants - Survey and Detection - Disease Transmission - Management - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

The Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, is widely distributed in southern Asia. It is an important pest of citrus in several countries as it is a vector of a serious citrus disease called greening disease or Huanglongbing. This disease is responsible for the destruction of several citrus industries in Asia and Africa (Manjunath 2008). Until recently, the Asian citrus psyllid did not occur in North America or Hawaii, but was reported in Brazil, by Costa Lima (1942) and Catling (1970).

Figure 1. Adult Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. Photograph by Douglas L. Caldwell, University of Florida.

In June 1998, the insect was detected on the east coast of Florida, from Broward to St. Lucie counties, and was apparently limited to dooryard host plantings at the time of its discovery. By September 2000, this pest had spread to 31 Florida counties (Halbert 2001).

Diaphorina citri is often referred to as citrus psylla, but this is the same common name sometimes applied to Trioza erytreae (Del Guercio), the psyllid pest of citrus in Africa. To avoid confusion, Trioza erytreae should be referred to as the African citrus psyllid or the two-spotted citrus psyllid (the latter name is in reference to a pair of spots on the base of the abdomen in late stage nymphs). These two psyllids are the only known vectors of the etiologic agent of citrus greening disease (Huanglongbing), and are the only economically important psyllid species on citrus in the world. Six other species of Diaphorina are reported on citrus, but these are non-vector species of relatively little importance (Halbert and Manjunath 2004).

Distribution (Back to Top)

Diaphorina citri ranges primarily in tropical and subtropical Asia and is reported from the following geographical areas: Afghanistan, Caribbean (Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, Jamaica, Dominican Republic, Cuba, Puerto Rico, plus interceptions from St. Thomas and Belize), Central America (Guadaloupe), China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mauritius, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippine Islands, Reunion Island, Ryukyu Islands, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, South America (Argentia, Brazil, Venezuela), Taiwan, Thailand, the United States and some of its territories (Halbert and Núñez 2004a)

The discovery of Diaphorina citri in Saudi Arabia (Wooler et al. 1974) was the first record from the Near East. Trioza erytreae also occurs in Saudi Arabia, preferring the eastern and highland areas where the extremes of climate are present, whereas Diaphorina citri is widespread in the western, more equitable coastal areas.

In the U.S. and its territories, this species is present in Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Guam, Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, Puerto Rico, South Carolina, Texas, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. In late May 2008, specimens were discovered in Jefferson and Orleans Parishes, Louisiana. On September 2, 2008, the psyllid was first detected in San Diego County, California. On October 27, 2009, the psyllid was discovered in Yuma County, Arizona. On April 21, 2010, surveys determined that the psyllid was present in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USDA 2010b).

As of June 2010, the following U.S. areas are quarantined due to the presence of the Asian citrus psyllid (USDA 2010c):

- Alabama: entire state

- Arizona: portion of Yuma County (USDA 2010b)

- California: southern areas (USDA 2010a)

- Florida: entire state

- Georgia: entire state

- Guam: entire territory

- Hawaii: entire state

- Louisiana: entire state

- Mississippi: entire state

- Puerto Rico: entire commonwealth.

- South Carolina: southeastern area

- Texas: entire state

- Virgin Islands - entire Territory (USDA 2010b)

Description and Identification (Back to Top)

Adults: The adults are 3 to 4 mm long with a mottled brown body. The head is light brown, whereas Trioza erytreae has black head. The forewing is broadest in the apical half, mottled, and with a brown band extending around the periphery of the outer half of the wing. This band is slightly interrupted near the apex (in Trioza erytreae, band is broadest at middle, unspotted and transparent). The antennae have black tips with two small, light brown spots on the middle segments (in Trioza erytreae, antennae are nearly all black). A living Diaphorina citri is covered with whitish, waxy secretion, making it appear dusty.

Figure 2. Adult Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. Photograph by Jeffrey Lotz, FDACS-Division of Plant Industry.

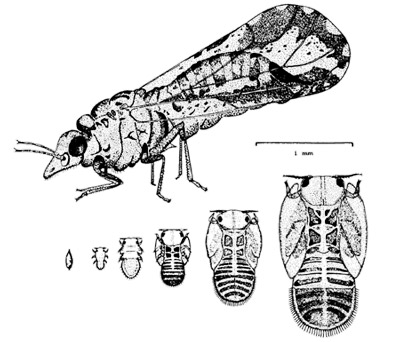

Nymphs: Diaphorina citri nymphs are 0.25 mm long during the 1st instar, and 1.5 to 1.7 mm in last (5th) instar. Their color is generally yellowish-orange. There are no abdominal spots, whereas in Trioza erytreae, advanced nymphs have two basal dark abdominal spots. The wing pads in Diaphorina citri are large, while Trioza erytreae has small pads. In Diaphorina citri, large filaments are confined to the apical plate of the abdomen (in Trioza erytreae, there is a fringe of fine white filaments around the whole body, including head).

Figure 3. Nymphal stages of the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. Photograph by David Hall, USDA.

Figure 4. The white waxy excretions of the nymphs are an indicator of the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. Photograph by Douglas L. Caldwell, University of Florida.

Figure 5. Adult female and nymphal instars of Asian citrus psyllid. Drawing by Division of Plant Industry.

Eggs: The eggs of Diaphorina citri are approximately 0.3 mm long, elongate, almond-shaped, thicker at the base, and tapering toward the distal end. Newly laid eggs are pale, but then turn yellow and finally orange before hatching. The eggs are placed on plant tissue with the long axis vertical to surface. Trioza erytreae eggs are laid with the long axis horizontal to surface.

Figure 6. Eggs of the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. Photograph by Douglas L. Caldwell, University of Florida.

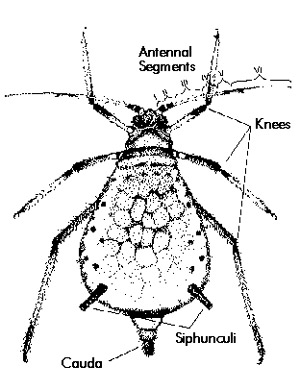

Identifications having regulatory significance should be made by taxonomists with adequate reference materials. Psyllids as a group are most likely to be confused with aphids as these latter insects are common on tender citrus leaves. But adult psyllids are active jumping insects and aphids are sluggish. In addition, aphids usually have four- to six-segmented antennae, while psyllid antennae usually have 10 segments. Most aphids have cornicles on the abdomen, while psyllids lack cornicles.

Figure 7. Brown citrus aphid - adult wingless form.

Life History (Back to Top)

Eggs are laid on tips of growing shoots on and between unfurling leaves. Females may lay more than 800 eggs during their lives. Nymphs pass through five instars. The total life cycle requires from 15 to 47 days, depending upon the season. Adults may live for several months. There is no diapause, but populations are low in winter (the dry season). There are nine to 10 generations a year; however, 16 have been observed in field cages.

Damage (Back to Top)

Schwarz et al. (1974) listed four reasons why the symptoms of greening in Southeast Asia were often different from those in South Africa. These reasons included the more tropical climate of Asia keeping mature fruit green, citrus variety differences, differences in the heat tolerance of the vectors leading to different disease distribution in the grove, and differences in the virulence of the strains of the pathogen.

Figure 8. Feeding damage caused by the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, to citrus foliage. Photograph by University of Florida.

Figure 9. Huanglongbing or greening disease damage to a sweet orange tree. Photograph by Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Host Plants (Back to Top)

Mainly Citrus spp., at least two species of Murraya, and at least three other genera, all in the family Rutaceae.

Survey and Detection (Back to Top)

Nymphs: The nymphs are always found on new growth, and move in a slow, steady manner when disturbed.

Adults: The adults leap when disturbed and may fly a short distance. They are usually found in large numbers on the lower sides of the leaves with heads almost touching the surface and the body raised almost to a 30° angle. The period of greatest activity of the psyllid corresponds with the periods of new growth of citrus. There are no galls or pits formed on the leaves as caused by many other kinds of psyllids. The nymphs are completely exposed, while the nymphs of Trioza erytreae are partially enclosed in a pit. Citrus trees in advanced stages of decline are somewhat similar to those affected by tristeza. Field recognition of greening disease in Asia from symptoms alone is difficult. Very similar leaf symptoms may be caused by a wide variety of factors varying from nutritional disorders to the presence of other diseases such as root rots and gummosis, tristeza, and exocortis.

Capoor et al. (1974) described greening symptoms of citrus as trees showing stunted growth, sparsely foliated branches, unseasonal bloom, leaf and fruit drop, and twig dieback. Young leaves are chlorotic, with green banding along the major veins. Mature leaves have yellowish-green patches between veins, and midribs are yellow. In severe cases, leaves become chlorotic and have scattered spots of green. Fruits on greened trees are small, generally lopsided, underdeveloped, unevenly colored, hard, and poor in juice. The columella (the internal, central columnlike structure found in citrus and other fruits) was found to be almost always curved in sweet orange fruits and apparently is the most reliable diagnostic symptom of greening. Most seeds in diseased fruits are small and dark colored.

Figure 10. Twig dieback caused by Huanglongbing or greening disease to a Murcott tree. Photograph by Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Figure 11. Grapefruit damage caused by Huanglongbing or greening disease. Lopsided fruit are a symptom of greening disease. Note the extreme distortion of the columella, the central columnlike structure found in citrus and other fruits. Photograph by Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

Disease Transmission (Back to Top)

Huanglongbing (HLB) is caused by a phloem-limited bacterium that has a true cell wall. There are at least three forms or species: Candidatus L. africanus causing African HLB; Candidatus L. asiaticus causing Asian HLB; and a new varient found in Brazil, tentatively called Candidatus L. americanus. Asian HLB is the bacterium found in Florida (Chung and Brlansky 2009). Capoor et al. (1974) reported a high percentage of transmission by tissue grafts. They found that 4th and 5th instar nymphs and adults could affect transmission. Diaphorina citri requires an incubation period before it can transmit the pathogen, which it retains for life following a short access feeding (15 to 30 minutes) on a diseased plant. Infectious nymphs retain their ability to vector the disease into adulthood. Adult psyllids can transmit the pathogen that causes greening after feeding for as little as 15 minutes, but transmission was low. One hundred percent infection was obtained when the psyllids fed for one hour or more. Capoor et al. (1974) indicated that the pathogen multiplied in the body of the psyllid and that there was an absence of transovarial transmission. They summarized differences between D. citri and Trioza erytreae in various aspects of greening transmission.

Figure 12. Symptoms of greening disease, Liberobacter spp, on citrus. Photograph by University of Florida.

Management (Back to Top)

Workers in India reported that Diaphorina citri can be controlled effectively with a wide range of modern insecticides. Injection of trees with tetracycline antibiotics to control greening disease was effective where the vector can be kept under control.

In countries where greening spread over long distances, it occurred because of the movement of infected and infested nursery stock. Only clean and healthy plants should be transported. In areas with low incidence of greening disease, any infected trees should be removed to prevent them from being reservoirs of the pathogen.

Natural enemies of Diaphorina citri include syrphids, chrysopids, at least 12 species of coccinellids, and several species of parasitic wasps, the most important of which is Tamarixia radiata (Waterston). Tamarixia radiata was introduced in Florida (intentionally) and the Rio Grande Valley of Texas (accidentally) (Michaud, personal communication).

Figure 13. Nymphs of the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, killed by the ectoparasitoid wasp Tamarixia radiata. Photograph by University of Florida.

In the United States and its territories, areas with Diaphorina citri are under quarantine (USDA 2010b). International quarantines, enacted by other countries, may also be placed on countries with Diaphorina citri.

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Atwal AS, Chaudhary JP, Ramzan M. 1970. Studies on the development and field population of citrus psylla, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Psyllidae: Homoptera). Journal of Research Punjab Agricultural University 7: 333-338.

- Bindra OS, Sohi BS, Batra RC. 1974. Note on the comparative efficacy of some contact and systemic insecticides for the control of citrus psylla in Punjab. Indian Journal of Agricultural Science 43: 1087-1088.

- Capoor SP, Rao DG, Viswanath SM. 1974. Greening disease of citrus in the Deccan Trap Country and its relationship with the vector, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. p. 43-49. In Weathers LG, Cohen M (editor). Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the International Citrus Virology, University of California, Division of Agricultural Sciences.

- Catling HD. 1970. Distribution of the psyllid vectors of citrus greening disease, with notes on the biology and bionomics of Diaphorina citri. FAO Plant Protection Bulletin 18: 8-15.

- Costa Lima AM. da. 1942. Homopteros. Insetos do Brazil 3: 1-327. Esc. Na. Agron. Min. Agr.

- Halbert SE, Sun X, Dixon W. (2001). Asian citrus psyllid update. (no longer available online).

- Halbert SE. (2006). Asian citrus psyllid - A serious exotic pest of FL citrus. (no longer available online).

- Hall DG. 2006. A closer look at the vector: Controlling the Asian citrus psyllid is the key to managing citrus greening. Citrus & Vegetable Magazine 70 (5): 24-26.

- Hall DG, Hentz MG, Adair Jr RC. 2008. Population ecology and phenology of Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) in two Florida citrus groves. Environmental Entomology 37: 914-924.

- Husain MA, Nath D. 1927. The citrus psylla (Diaphorina citri, Kuw.) (Psyllidae: Homoptera) Memoirs of the Department of Agriculture India 10: 1-27.

- Mangat BS. 1961. Citrus psylla (Diaphorina citri Kuway) and how to control it. Citrus Industry 42: 20.

- Mathur RN. 1975. Psyllidae of the Indian Subcontinent. Indian Council of Agricultural Research, New Delhi. 429 pp.

- Michaud JP. Personal communication. (19 October 2002).

- Miyakawa T, Tanaka H, Matsui C. 1974. Studies on citrus greening disease in southern Japan. p. 40-42 In Weathers LG, Cohen M (editor). Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the International Citrus Virology, University of California, Division of Agricultural Sciences.

- Moll JN, van Vuuren SP. 1977. Greening Disease in Africa. 1977 International Citrus Congress, Orlando, Florida, Program and Abstracts. 95 pp.

- Pande YD. 1971. Biology of citrus psylla, Diaphorina citri Kuw. (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). Israel Journal of Entomology 6: 307-310.

- Raychaudhuri SP, Nariani, Ghosh SK, Viswanath SM, Kumar D. 1974. Recent studies on citrus greening in India. p. 53-57. In Weathers LG, Cohen M (editor). Proceedings of the 6th Conference of the International Citrus Virology, University of California, Division of Agricultural Sciences.

- Schwarz RE, Knorr LC, Prommintara M. 1974. Citrus greening disease in Thailand FAO Technical Document No. 93: 1-14.

- USDA. 1959. Insects not known to occur in the United States. Citrus psylla (Diaphorina citri Kuwayama). No. 88 of Series. Cooperative Economic Insect Report 9: 593-594.

- Wooler A, Padgham D, Arafat A. 1974. Outbreaks and new records. Saudi Arabia. Diaphorina citri on citrus. FAO Plant Protection Bulletin 22: 93-94.