common name: vespiform thrips

scientific name: Franklinothrips vespiformis Crawford (Insecta: Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae)

Introduction - Synonymy - Distribution - Description - Life Cycle - Hosts - Economic Importance - Selected References

Introduction (Back to Top)

Franklinothrips vespiformis Crawford (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae) is a predatory thrips with a pantropical distribution. The distinctive red, humped-back larvae and fast-moving ant-like adults are predaceous on small arthropods. In addition to being easily mistaken for an ant, this beneficial thrips is unusual in that it constructs a silken cocoon within which it pupates. Males of this species are rare.

Figure 1. Female vespiform thrips showing constricted waist and white band. Photograph by Runqian Mao, University of Florida.

Synonymy (Back to Top)

- Aeolothrips vespiformis Crawford DL, 190

Distribution (Back to Top)

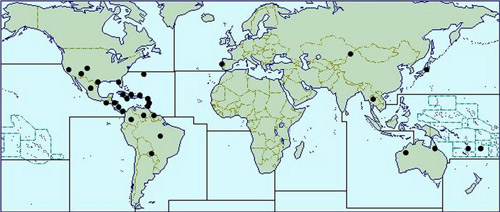

Franklinothrips vespiformis is presumed native to Central America, but is now found in many regions, including the United States (Arizona, California, Colorado, Texas, Florida), many Caribbean and South American countries, India, Thailand, Fiji, French Polynesia, Galapagos Islands, New Caledonia and, most recently, Australia (Queensland & northern Western Australia) and Japan (Arakaki and Okajima 1998, Mahaffey and Cranshaw 2010, Mound and Reynaud 2005, Hoddle et al. 2012). It is also sold in Europe and Israel as a biological control agent for use in greenhouses. This species was originally described as an easily recognized species, distinct from Aeolothrips (Hood 1913). Particularly similar in structure to Franklinothrips vespiformis is the Central American species Franklinothrips orizabensis, but the latter has the forewings rather broader at the apex and without a pale sub-apical area (Mound and Reynaud 2005).

Figure 2. Known Franklinothrips vespiformis distribution (after Mound and Reynaud 2005, Greathead and Greathead 1992, Hoddle et al. 2012, Mahaffey and Cranshaw 2010, UK CAB International 2010).

Description (Back to Top)

Franklinothrips vespiformis undergoes partial metamorphosis, developing through five immature stages: egg, larva I and II, pupa I (pro-pupa) and II (pupa) and adult (Arakaki and Okajima 1998, Hoddle et al. 2012).

Eggs: The eggs are kidney-shaped, translucent white, and about 0.38 mm long and 0.13 mm wide. Eggs are oviposited into leaf tissue.

Larva: First instars are pale yellow but quickly develop red bands. Red banding becomes very pronounced in the second instars. All larvae have seven-segmented antennae and the three distal segments are closely fused. Legs are transversely banded with red hypodermal pigments. In larva I, the head, prothorax and femora are pale (without red pigments); antennal segment III is approximately 4 times as long as broad. In larva II, head, prothorax and femora are red; antennal segment III is approximately 8 times as long as broad.

Pupa: Second instars pupate inside semi-transparent silken sheaths (cocoons). Cocoons are white and oval-shaped, about 2.7 mm long and 1.3 mm in width. Antennae are folded posteriorly and lay dorsally on the head. There is a pro-pupal stage (pupa 1) followed by a pupal stage (pupa 2). The wing buds are well developed in both stages, but shorter in pupa I.

Adults: Females are myrmiciform with long legs and a constricted waist; body length is 2.5-3.0 mm. Adult females are brown to black, with banded black and white wings and a white band at the base of the abdomen. Forewings are slender with a rounded apex. Antennae are nine-segmented, with segments I-III yellow and segment III approximately as long as head. The abdomen is broadest at segment V or VI just like the pedicels of ants. The constriction is pronounced by white bands on the second and third abdominal segments. Males are very rare and less ant-like in appearance (less constricted waist), smaller than females, with longer, darker antennae, and commonly with paler wings.

Figure 3. Egg laying of Franklinothrips vespiformis, showing ovipositor. Photograph by Runqian Mao, University of Florida.

Figure 4. Franklinothrips vespiformis newly emerged larva; egg to right. Photograph by Runqian Mao, University of Florida.

Figure 5. Franklinothrips vespiformis larva II feeding on nymph of Scirtothrips dorsalis. Photograph by Runqian Mao, University of Florida.

Figure 6. Pupa of Franklinothrips vespiformis inside cocoon. Photograph by Runqian Mao, University of Florida.

Life Cycle (Back to Top)

Franklinothrips vespiformis is active at temperatures above 18°C, with development from egg to adult completed in approximately 3 weeks at 27°C (Larentzaki et al. 2007a). Diapause has not been reported with this species. Females may live for up to 2 months and lay 150-200 eggs. Eggs are inserted individually inside leaf tissue by the female’s curved ovipositor (Entocare 2013). A yellowish protective secretion is deposited over the eggs. Larvae and adults move quickly to catch prey, which they hold with their forelegs while feeding. They may become cannibalistic when crowed together in the laboratory (Arakaki and Okajima 1998). Pupae of Franklinothrips are formed inside a silken cocoon on the undersides of leaves or at ground level, which appears to be an adaptation to predation (Hoddle et al. 2001a). Franklinothrips vespiformis is usually unisexual. Males have been observed in its native South America but not in its introduced range in Asia, possibly since populations exhibiting parthenogenesis spread more easily than sexual forms.

Throughout its range, Franklinothrips vespiformis has been found on low growing plants and shrubs, including vegetables and fruits (kidney bean, melon, gourd, cucumber, avocado, eggplant and citrus) and ornamental sunflowers (Arakaki and Okajima1998, Callan 1943, Cox et al. 2006, Moulton 1932). The authors have collected Franklinothrips vespiformis at relatively low densities from plumbago alongside roadways and in sweep net samples from grassland weeds in Central Florida.

Figure 7. Collecting Franklinothrips vespiformis from ornamental plumbago shrubs. Photograph by Runqian Mao, University of Florida.

Hosts (Back to Top)

Franklinothrips vespiformis and Franklinothrips spp. in general prey upon various pest thrips and other small arthropods. Noted prey items include red banded thrips, Selenothrips rubrocinctus Giard; Caliothrips insularis Hood; Dinurothrips hookeri Hood; chilli thrips, Scirtothrips dorsalis Hood; melon thrips, Thrips palmi Karny; onion thrips, Thrips tabaci Lindeman; western flower thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis Pergande; Franklinothrips intonsa Trybom; greenhouse thrips, Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis Bouché; and Scolothrips asura Ramakrishna & Margabandhu (Callan 1943, Okajima et al. 1992, Arakaki and Okajima 1998, Hoddle 2003a, Pizzol et al. 2008). In laboratory tests, Franklinothrips vespiformis have been shown to take alternative prey items, such as spider mites, immature whiteflies, leafminer larvae and psyllid eggs (Arakaki and Okajima 1998; personal observation). Some Franklinothrips species can sustain themselves for short periods on pollen or sap (Hoddle et al. 2003b, 2001b) which may result in accidental intoxication by systemic insecticides.

Figure 8. Franklinothrips vespiformis feeding on adult Scirtothrips dorsalis. Photograph by Runqian Mao, University of Florida.

Figure 9. Franklinothrips vespiformis feeding on whitefly eggs. Photograph by Runqian Mao, University of Florida.

Economic Importance (Back to Top)

Predatory thrips are important natural enemies of pest species in natural and agricultural systems (Ananthakrishnan 1993). At least sixteen predatory Franklinothrips species are described from tropical and subtropical countries, but amongst these Franklinothrips vespiformis is the most widespread (Hoddle et al. 2012, Mound and Reynaud 2005). In California, another species, Franklinothrips orizabensis, is an important predator of thrips pests on avocado trees. This latter species has been the subject of extensive research, including augmentative release (Hoddle et al. 2004). Both Franklinothrips vespiformis and Franklinothrips orizabensis have been introduced in Europe and Israel as a biological control agent against thrips and mite pests in greenhouses (Loomans and Vierbergen 1999; Cox et al. 2006). At the time of writing, Franklinothrips vespiformis is sold for use “in botanical gardens, zoos, interior landscapes, research greenhouses, nurseries with ornamental plants as well as outdoors in subtropical regions” (Entocare 2013). High cost of mass rearing, poor tolerance to low temperature storage, and the lack of research have been cited as potential problems with the larger scale commercialization of Franklinothrips vespiformis (Larentzaki et al. 2007b).

Selected References (Back to Top)

- Ananthakrishnan TN. 1993. Bionomics of thrips. Annual Review of Entomology 38: 71-92.

- Arakaki N, Okajima S. 1998. Notes on the biology and morphology of a predatory thrips, Franklinothrips vespiformis (Crawford) (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae): First record from Japan. Entomological Science 1: 359-363.

- Callan E. 1943. Natural enemies of the cacao-thrips. Bulletin of Entomological Research 34: 313-321.

- Cox PD, Matthews L, Jacobson RJ, Cannon R, MacLeod A, Walters KFA. 2006. Potential for the use of biological agents for the control of Thrips palmi (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) outbreaks. Biocontrol Science and Technology 16: 871-891.

- Entocare CV. 2013. Natural enemies thrips. Wageningen Pest Control. (February 10, 2015)

- Greathead DJ, Greathead AH. 1992. Biological control of insect pests by insect parasitoids and predators: the BIOCAT database. Biocontrol News and Information, 13: 61N-68N.

- Hoddle MS. 2003a. The effect of prey species and environmental complexity on the functional response of Franklinothrips orizabensis: A test of the fractal foraging model. Ecological Entomology 28: 309-318.

- Hoddle, MS. 2003b. Predation behaviors of Franklinothrips orizabensis (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae) towards Scirtothrips perseae and Heliothrips haemorrhoidalis (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Biological Control 27: 323-328

- Hoddle MS, Mound LA, Paris DL. 2012. Thrips of California. CBIT Publishing, Queensland. (February 14, 2015)

- Hoddle MS, Oevering P, Philips PA, Faber BA. 2004. Evaluation of augmentative releases of Franklinothrips orizabensis for control of Scirtothrips perseae in California avocado orchards. Biological Control 30: 456-465.

- Hoddle MS, Oish K, Morgan D. 2001a. Pupation biology of Franklinothrips orizabensis (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae) and harvesting and shipping of this predator. Florida Entomologist 84: 272-281.

- Hoddle MS, Jones J, Oishi K, Morgan D, Robinson L. 2001b. Evaluation of diets for the development and reproduction of Franklinothrips orizabensis (Thysanoptera: Aeolothripidae). Bulletin of Entomological Research 91: 273-280.

- Hood JD. 1913. On a collection of Thysanoptera from Panama. Psyche 20: 119-124.

- Larentzaki E, Powell G, Copland MJ. 2007a. Effect of temperature on development, overwintering and establishment potential of Franklinothrips vespiformis in the UK. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 124: 143-151.

- Larentzaki E, Powell G, Copland MJ. 2007b. Effect of cold storage on survival, reproduction and development of adults and eggs of Franklinothrips vespiformis (Crawford). Biological Control 43: 265-270.

- Loomans AJM, Vierbergen G. 1999. Franklinothrips: perspectives for greenhouse pest control. Bulletin OILB/SROP 22(1): 157-160.

- Mahaffey LA, Cranshaw WS. 2010. Thrips species associated with onion in Colorado. Southwestern Entomologist 35: 45-50.

- Moulton D. 1932. The Thysanoptera of South America. Revista de Entomologia 2: 464-465.

- Mound LA, Reynaud P. 2005. Franklinothrips; a pantropical Thysanoptera genus of ant-mimicking obligate predators (Aeolothripidae). Zootaxa 864: 1-16.

- Okajima S, Hirose Y, Hakita H, Takagi M, Naponpeth B, Buranapanichpan S. 1992. Thrips on vegetable in Southeast Asia. Applied Entomology and Zoology 27: 300-303.

- Pizzol J, Nammour D, Ziegler JP, Voisin S, Maignet P, Olivier N, Paris B. 2008. Efficiency of Neoseiulus cucumeris and Franklinothrips vespiformis for controlling thrips in rose. ISHS Acta Horticulturae 801: 1493-1498.

- UK CAB International 2010. Franklinothrips vespiformis datasheet. (February 14, 2015)